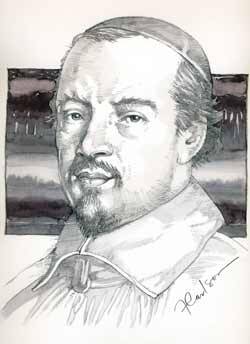

The 400th anniversary of the birth of Jean-Jacques Olier on Sept. 20 is likely to pass unnoticed in the United States, given the relatively low visibility of his foundation, the Sul-picians. Diocesan priests released by their bishops for the work of seminary education, the Sul-picians are named for Olier’s parish of St. Sulpice in Paris (recently made famous, or infamous, by Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code). In Quebec and elsewhere in Canada, they still enjoy something of the kind of prominence they once had in the United States in the early days, with a cardinal, bishops and a major seminary. In the United States their seminaries are now down to two, Baltimore and San Francisco, and they have not had a U.S. bishop appointed from among their ranks in almost two centuries. The reasons for this lack of prestige or fall from ecclesiastical favor merit another essay. But perhaps for now, the Sulpicians’ perch on the edge of ecclesiastical power affords a vantage point for a critical perspective on the church and the priesthood. Olier’s birthday offers us all a chance to share in something of the same.

Olier’s life (1608-57) fell within a time when the priesthood was truly struggling to breathe, let alone laugh. Olier’s indirect spiritual mentor, Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle, the founder of the French Oratory, had written of the decrease of authority, learning and holiness among the priests of the time and the need to recover them once again. Bérulle’s reformist project had reached Olier through his spiritual advisor, Father Charles de Condren, whose own reform efforts on behalf of the church corresponded to Bérulle’s concerns.

Authority, Learning and Holiness

Without learning and holiness, such authority as the priesthood still possessed teetered dangerously close to becoming a shell covering up power plays and careerism. Well-positioned clergy wanted ever more lucrative benefices (parishes and dioceses). Olier’s aristocratic mother wanted this for her own son, who must have greatly disappointed her by his two refusals of a bishopric and by his determination not only to accept the benefice of St. Sulpice, but actually to serve as its pastor (not always true in other parishes at the time). Olier seemed committed to a reformed and Spirit-energized parish of St. Sulpice, which could serve as a hub from which would radiate further renewal in Paris and beyond. Priests, he knew, were a central part of this hub-approach to renewal. Their leadership was vital, but it had to be a true leadership, not simply a career in search of money or status. Hence he founded a seminary within the parish itself, perhaps the first such in France (although the Vincentians might give this honor to St. Vincent de Paul, who played an important formative role for Olier). In Olier’s view, seminarians needed to learn that they were there to serve the people.

Centuries before the Second Vatican Council, Olier wrote enthusiastically about the priesthood of the faithful and was mindful of the need for a more active and responsible laity. The Jansenists nearly chased him out of his parish for his attempts to foster frequent Communion, which, until then, was a practice reserved to the ordained priest. But the “presbyteral” priests, so to speak, would normally assume leadership, and Olier had few illusions about the costs involved in this. One of his favorite images for the priest was that of “host-victim,” a liturgical reference to Jesus’ life of sacrifice but also an anticipation of a priesthood of service rather than elitism.

Learning was another crucial element in Bérulle’s and Olier’s reformist triad. Olier’s key tactics were a solid education for the clergy, both at the seminary and the Sorbonne, and for the adult laity. Efforts to meet the growing demands by the better-positioned laity for adult education were met through an impressive list of popular publications. We know, for example, that one of his works, The Christian Day, went through six editions in the 17th century. These were the kinds of educational reform boasted about by the French Protestants as well, and there is no shame in recognizing that Olier probably learned a thing or two from them. Learning from them no doubt also meant much for the quality of preaching, for example, or for efforts to foster a more critical laity.

The 17th century initiated our so-called turn to modernity. Descartes and Bérulle knew each other. One might ask just how “modern” Olier himself was in his learning. Like Bérulle, but without his metaphysical leanings, Olier seems to have returned to a more Pauline and Johannine theology via the church fathers, especially the Greek fathers. He was modern in the sense that he eagerly participated in the biblical and patristic renewal of his time. He even, in a quite modern way, referred to the Bible as a ciborium in which Christ dwells. But he also anticipated today’s “antimoderns” or “postmoderns,” in the sense that he did not move in the direction of the more Cartesian, rationalist theology of the scholastic manuals, but in the direction of a more mystical, spiritual and pastoral style of theology.

Holiness—today one might say “spirituality”—was Monsieur Olier’s chief love and focus, and fittingly so, for he likely considered it the chief partner in the triad of authority, learning and holiness. The new critical edition of his Treatise on Holy Orders reveals a quite mystical understanding of the priesthood, distinct from either a more legalistic, canonical view based on power or from a more moralistic one, which might be more characteristic of the Jansenist view of the priesthood. In his view, the priest is one who is called by grace to participate in the mysteries of Jesus, and to be deeply rooted in his interior and exterior dispositions, undergoing purification, illumination and mystical union. From this presbyteral hub, chiefly through education, spiritual direction and liturgy, this mystical spirituality was to radiate out to the priesthood of the faithful at large.

Signs of the Spirit

Olier’s triad of authority, learning and holiness anticipated the later Baron Friedrich von Hügel’s notion of institutional, intellectual and mystical elements of the church. Like Bérulle and Olier, Von Hügel argued that these three needed to remain in a fruitful and mutually critical interchange for the church to remain healthy. Otherwise the church, her people and her priests could not breathe properly, let alone laugh. These images of breathing and laughing come from a passage in Father Olier’s Mémoire, in which he describes his liberation from a spiritual and physical cramp he had experienced for some time. By extension, one could say that the church of his time was likewise experiencing some serious cramping, and that ecclesial breathing and laughing could be regarded as signs of liberation. To employ another of Olier’s favorite expressions, they were manifestations of “se laisser à l’Esprit,” opening ourselves up to the Spirit. Joy is one of the Spirit’s most desired gifts (Gal 5:22), and the Spirit has been described as the “breath” through which Father and Son speak.

One challenge we might take from the occasion of Father Olier’s birthday celebration is to ask ourselves how well all of us—the priesthood of the faithful at large and the presbyteral priesthood in particular—are remaining faithful to the triad of institutional authority, theological and humane learning in general and spirituality in mutual and critical dialogue. Each of these suffers without the other.

Probably few of us do not have some issues with institutional authority, including what we might perceive as its inertia or its blindness, among many forms of ecclesiastical cramps. Institutions seem peculiarly prone to these maladies, for they are meant to be rather stable and solid, providing an infrastructure from which various projects might emerge. Truly stable structures, ones that really work and enjoy the confidence of the people they are meant to serve, take time and careful nurturing. What takes centuries to build up can all too easily be crushed by imprudent leaders. Naturally, therefore, there is a kind of built-in institutional resistance to much tampering. But therein lies a lurking danger.

As a result, we must look to learning as a way of keeping institutions healthy. In the first century, Paul the theologian took Peter the institutional shepherd to task, and ever since in the church there has been a somewhat rocky relationship between theologians and scholars and the hierarchy. Naturally there is a kind of fruitful tension here, as there should be for the church to remain healthy. But learning can carry us only so far, and one does not have to venture far into theology before learning that theologians have their blinders too.

Olier’s instinct was to look to spirituality (which for him developed primarily through the sacramental and liturgical life) as the deeper soil from which would emerge a healthy theology and a sound institutional church. But here too, much turns on what is meant by spirituality. We have all likely met the person, whether hierarch, priest or layperson, who thought of spirituality as a matter of quasi-piety: “If we’re pious, we’ll just roll over in humble self-disregarding obedience.” Spirituality can degenerate into a sentimentalism or intellectual infantilism when not nourished by solid scholarship, or into elitisms of all sorts when not nourished by participation in the church’s larger life. For Olier, the chief form of holiness was an openness to the Spirit that keeps us self-critical and growing. A formula he recommended for prayer was “Jesus before our eyes [minds], in our hearts [the wellspring of the Spirit], and in our hands [a metaphor for our commitments, institutional and otherwise].” The three elements are intriguingly present in their pleasingly simple prayer formula.

Breathing and especially laughing were important indicators for Olier of the Spirit’s presence. By laughing, Olier meant a truly liberating kind of laughter that comes from the deep-down sense that reform, personal and ecclesial, is not all on our shoulders. We may stumble and fall along the way, but we can laugh, for we sense we are being supported by the greater power of the Spirit. That kind of laughter has nothing to do with arrogant intellectual or institutional closure.

Happy birthday, Father Olier, and congratulations, priests of St. Sulpice.