George Tooker (b.1920) is a living American artist whose work, and in some respects whose life, seems especially pertinent to our times. Deeply spiritual and therefore attuned to social injustice and destructive societal trends, Tooker painted his most provocative works as protests against racism, alienation, government surveillance of citizens and homophobia. On his canvases Tooker shows viewers what intolerance, suspicion, prejudice and lack of community look like, which makes his paintings ominously affecting. Like Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth and Jacob Lawrence in the United States, and like Balthus in Europe, Tooker insisted on making figurative art when the avant garde had moved into modernism and abstraction and had pronounced representational art passé if not dead.

“George Tooker: A Retrospective,” now on view at the National Academy Museum in New York City (through Jan. 4), is the first retrospective of Tooker’s work in 30 years. The show should not be missed. It will travel to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (Jan. 30-April 5) and to the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio (May 1-Sept. 6, 2009). These three museums collaborated on the exhibition and produced an excellent catalogue. A recipient of the 2007 National Medal of Arts and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Tooker deserves to be more widely known.

Of Cuban-Dutch descent, Tooker was educated at Phillips Academy during the Great Depression and at Harvard before World War II. In these settings, Tooker felt keenly his mixed ethnicity and understood something of the “outsider status” that racial discrimination confers. In art Tooker found a way of cultivating an interior life and it gave him a powerful tool for communicating his observations. “Painting,” he once said, “is an attempt to come to terms with life.”

Over six decades, the artist has reflected on social injustices, on personal memories and on classical themes. Yet even when a Tooker painting mirrors some societal trend, it is personal at its core. Ultimately Tooker focuses on the figure because his insights concern persons and how they do, and do not, relate to one another.

For example, in “Ward” (1970-71), the artist presents a roomful of identical hospital beds occupied by identical looking young men under white sheets; these beds look rather like open coffins, which may be the point. Three older figures, two men and one white-haired woman are not reclining and are awake, but no one relates to anyone else—a common theme in Tooker’s protest paintings. Behind the cold white interior, hang large U.S. flags in red, white and blue, indicating that the place is a military hospital. Painted during the Vietnam War, this painting can be interpreted as a war protest, but it can also be seen more generally as a protest not only of our treatment of veterans, but of the impersonal way our society “cares” for all people who are ill or injured. Though nearly 40 years have passed since Tooker made this image, it remains relevant.

Son of the Renaissance

It is ironic that an artist who records contemporary life would use techniques from the Renaissance, but Tooker mixes his own egg tempera in the colors of Umbria and evinces an infatuation with perspective and architectural forms—all reminiscent of Italian Renaissance painters. His most famous painting, “Subway” (1950), bought by the Whitney the year it was created, shows a subway station from the inside, with its oppressively low ceilings, multiple stairwells and turnstiles—a complex exercise in perspective. What it illustrates is the alienation such an environment fosters among strangers. Anonymous individuals look past one another, a few men peer out eerily at the viewer, and the central figure, a woman in a red dress with a distressed expression, puts a protective hand over her body as though sensing danger. The whole image is made with tiny methodical brush strokes; not a hair is out of place in Tooker’s work. The perfection of the technique used to depict such imperfection within society is doubly jarring.

Other social protest paintings include “Government Bureau” (1956) in which bleary-eyed bureaucrats all with the same chilling face stare at the viewer through a hole in the opaque glass that separates them from those seeking service. Here the warm colors of the people’s garments contrast with the brash overhead lights, as they line up before a seemingly endless succession of cubicles. If Franz Kafka had been a painter, his work might have resembled this.

In “Landscape with Figures” (1966) the “land” is actually a warren of cubicles, each of which contains a man or a woman, like workers in a vast office seen from above. Some people have closed their eyes (perhaps to find more space within), while others look upward. No one looks happy, and no one engages with the others who sit just one thin wall away. A warm red pervades the entire painting, as though blood could course through the people depicted if only they would reach out to one another.

“I am after painting reality impressed on the mind so hard that it returns as a dream,” Tooker has said, “but I am not after painting dreams as such, or fantasy.”

In “Lunch” (1964) solitary men and women sit at lunch counters, each eating an identical sandwich. But Tooker adds a twist: a lone black man sits at the center of the picture. He is as ignored and as unseen as are all the other people, yet he seems even more alone by virtue of his being racially different. Tooker may be showing that integration does not mean the end of segregation, for isolation lies deeper still and separates people.

Looking at Race

Tooker depicts Latinos and African-Americans in crowds and street scenes, but also shows mixed-race couples at home (“Guitar,” “Window II” and “Window VII”). In “Window VII” (1963), a lovely nude female pulls back a yellow curtain and modestly gazes out; over one shoulder, the face of a gorgeous black man looks out; in the soft red-orange background a bit of the bed is showing; it is sensuous and carnal.

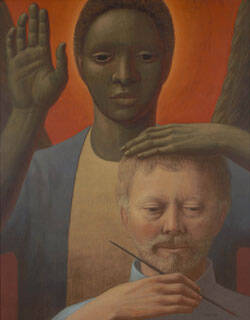

Tooker also painted a black Christ in the act of blessing the bread in “Supper” (1963); Jesus is about to break bread with two other men, both of them white. Tooker said that this image recalled the post-resurrection story of Christ at Emmaus. In “Dark Angel” (1999), Tooker expressed his own understanding of the vocation of the artist as divinely given. In this self-portrait, a black angel blesses Tooker, laying his hand on Tooker’s head as the artist holds a paint brush.

While the disturbing iconography in Tooker’s protest paintings is particularly powerful, his oeuvre offers more than social commentary. Some of his works are beautiful, even sublime. In “Fountain” (1950), a group of blond Adonnises, shirtless and barefoot, clad in light blue jeans, sit and stand around a large fountain as water shoots out and birds hover in a blue sky. While the men are not jovial, the scene is communal. In “Embrace I” (1979), Tooker presents the idealized image of a lovely young blonde couple in each other’s arms, alone on the hills; sunlight bathes the young woman’s face. And in “Embrace of Peace II” (1988), which has the same name as a part of the Catholic Mass, Tooker shows a young woman and man reaching for each other and looking directly at each other with intense, but not sexual, longing. Perhaps because our culture is oversaturated with images of lovers, many in poses more overtly sexual than those in Tooker’s work, his images of lovers are less memorable than his protest pieces, which show us what others do not.

Tooker’s “Girl Praying” (1977) is quietly moving; perhaps a Latino or an African-American, the subject holds her hands over her heart in a gesture like that of Mary at the Annunciation. She wears a blue coat, as Mary does in much of Western art, and does not look at the viewer. Instead, she seems in the midst of a mystical experience, communing with someone we cannot see. A golden glow behind her helps to project a religious mood. Such images within Tooker’s work are serene and contemplative, warm and peaceful. This too is countercultural.

An Artist in New York

During the 1940s Tooker was a young artist studying at the Art Students League in New York, where Reginald Marsh and Edward Hopper were teaching. He met Paul Cadmus, an artist 16 years older than he was, and the two became lovers. Their circle of friends included several distinguished artists: Jared French and his wife Margaret, Lincoln Kirstein, the ballet impresario, and George Platt Lynes, a photographer. French’s style, with its clean lines and well-formed figures, influenced Tooker. During this decade, Tooker’s work explored implicitly homosexual themes. One example is “A Game of Chess” (1946-47), in which Tooker deals with societal expectations of marriage. Here a young man who looks like Tooker is about to run away from a huge mother figure and her seductively dressed daughter, who appears ready to declare “checkmate.” In this masterpiece, the very floor on which the young man stands looks like a game board, on which his future will be determined by this move.

In 1949, Tooker formed a relationship with William Christopher, also an artist, who would become his lifetime partner until Christopher’s death in 1973. The two lived together in New York, then bought a home in Vermont, which is where Tooker still lives. Tooker and Christopher, who was raised by an African-American family after his parents died, became ardent supporters of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement.

Raised an Episcopalian, Tooker converted to Catholicism in 1976 after Christopher’s death, a transition facilitated by his friendship with a local Catholic priest. One finds a palpable sense of peace in Tooker’s later works. Some of his overtly religious works, including a set of Stations of the Cross, the seven sacraments (commissioned for a church in Vermont), and a resurrected Christ, are shown in the catalogue but are not part of the exhibit.

This retrospective of Tooker’s work allows the viewer to appreciate the balance the artist has achieved over a lifetime. His work points to what needs repair in our society and in our relationships, and yet it also it attests to the strength and beauty of love, community and faith.

View a slideshow of Goerge Tookers art.