Last night I stood outside the Media Operations Center in the darkness and quiet of the night. It was nearly 2:00 a.m., and I was all alone. It was my first experience of solitude, peace and prayer since arriving at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, two days earlier.

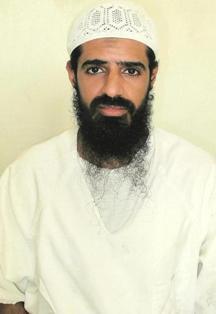

So far the whole experience of being here has, at times, been overwhelming. The schedule is full. Walk to the courtroom at 8:05 a.m. Attend the morning session of court from 9:00 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Grab a quick Subway sandwich, which was preordered in the morning. Return to court or watch the proceedings via closed circuit television from the media center. The whole time I am bombarded with information. The prosecution and defense present meticulous legal arguments. Sometimes the judge asks questions of clarification to better understand the arguments; at other times he aggressively rejects what he identifies as flawed reasoning. Meanwhile all eyes are on the five defendants, accused of plotting the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Reporters record every detail of their choice of clothing, headdress, length of beard (and even its color!), general mannerisms and especially their responses – sometimes in Arabic, sometimes in English – to the judge’s questions.

To add to this barrage of information, the press corps is trying to convey the experiences and information in an interesting manner and as quickly as possible. Until I spent a day in the Guantánamo media center, I did not realize how much Twitter dominates how we communicate with each other and even report the news. Everyone is tweeting, reading tweets and talking about the best tweets being passed around. This reporting occurs before, during and after the hearings, and for some, late into the evening. It is exciting, intense and exhausting. I am quickly learning through experience that it is simply impossible to report every interesting detail. Choices must be made.

This is a glimpse into my first 60 hours at Guantánamo Bay. I came here with the hope of learning more about the prison camp. In such close physical proximity to the 166 detainees for the first time, I hoped to pray “with” them and for them. But, at this point, I have not even been close to the prison camp; it is located on the far side of the base. On the base the press corps moves within a tightly restricted space in Camp Justice. I go the media center, I go to court (escorted by military personnel) and I go to the residential tents. Bright orange barriers and chain-link, razor-wire fences inhibit any free movement beyond Camp Justice.

This is a glimpse into my first 60 hours at Guantánamo Bay. I came here with the hope of learning more about the prison camp. In such close physical proximity to the 166 detainees for the first time, I hoped to pray “with” them and for them. But, at this point, I have not even been close to the prison camp; it is located on the far side of the base. On the base the press corps moves within a tightly restricted space in Camp Justice. I go the media center, I go to court (escorted by military personnel) and I go to the residential tents. Bright orange barriers and chain-link, razor-wire fences inhibit any free movement beyond Camp Justice.

Back to the late-night solitude – my first experience of interior tranquility since arriving at Guantánamo. I stood outside, alone, and faced the direction of the prison camp. I prayed “with” and for the detainees. I recalled some of their names, especially Yusef Abbas, Saidullah Khalid and Hajiakbar Abdulghupur, the three Uighur men who remain in custody. I tried to imagine ten years of imprisonment without charges or trials for the vast majority of the detainees. I also remembered Salim Hamdan, who was convicted in a military commission in 2008, only to have the conviction vacated just yesterday by a U.S. Court of Appeals. The court ruled 3 to 0 that Mr. Hamdan was unfairly prosecuted ex post facto, meaning he had been charged with crimes that did not exist at the time of his arrest.

Family Members Speak

As I prayerfully reflected on my day, however, my attention shifted to another visceral experience of suffering – that of family members who lost loved ones in the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

A few hours earlier I sat in a room with nine family members and only five members of the media. The family members graciously agreed to respond, on the record (and on camera), to some of our questions. Reporters asked for their reactions to decisions of the court, especially those favorable to the defendants. “Disgusting” and “ridiculous,” family members responded. One woman, who lost her son in the Pentagon, said, “To me these cannot be human beings; they are devils.”

Two particular women, who each lost a child in the attacks, expressed how faith has carried them through the darkest days. At the same time, however, they dismissed forgiveness as impossible. “No way.” I asked if it were possible even for their personal healing. “No.” A mother later explained, “The death penalty cannot even bring justice. They deserve to die. They deserve as much pain as can possibly be inflicted up them.” I sensed so much pain and suffering in that room. (I will write about the interview in greater depth later this week.)

At 2:30 a.m., much later than I anticipated staying awake, the night-duty soldier walked outside, and I shared my experience of listening to the family members. I expressed my hope that the family members would be able to, at some point, experience at least partial healing and freedom. While I cannot understand what they have endured for the past 11 years, it is my faith-inspired hope that the deplorable actions of 9/11 and the loss of their loved ones would not control their lives ad infinitum. A better life is possible. In fact God has promised “a new heaven and a new earth” in which God “will wipe every tear from our eyes, and there shall be no more death or mourning, wailing or pain” (Rev 21:2, 4). This is what I shared with the soldier.

She responded, “Only God is perfect. Religion is imperfect, and so are we. I wish we could all just get along.” I acknowledged the truth of her statement. And then another experience from the day came to me.

Shared Humanity

During the morning session in the courtroom, I noticed a military policeman (M.P.) talking with Ramzi Bin al Shibh, one of the defendants in the 9/11 trial. Mr. Bin al Shibh was seated in his chair, so the M.P. knelt beside him during the exchange. It was a friendly exchange, and it concluded with both men happily nodding in agreement. Then the M.P. moved to Walid bin Attash, another defendant, and likewise knelt beside him. It appeared as if the M.P. was helping coordinate something that required input from both defendants. After the conversation, both men smiled and nodded and the business of the court continued uninterrupted.

Now, at first look, this might appear to be an insignificant exchange. But let’s remember the context. The government claims that Al Qaeda committed an act of war against the United States on Sept. 11, 2001, in which the defendants are implicated, and that this war between Al Qaeda and the United States continues to this day. It is also important to remember that the defendants are not shackled while in court. They remain seated for the proceedings, but their arms and legs are allowed to move freely about. (Actual freedom of movement, not surprisingly, is significantly offset by the presence of about four M.P.’s for each defendant, seated against the left wall of the courtroom.)

For these reasons I looked at the exchange between each defendant and the M.P. with delightful amazement. Both parties were agreeable and pleasant. Whatever needed to be clarified or arranged among them appeared to have worked out. I did not notice any tension or ambivalence in them. The M.P. did not approach the defendants with any sign of “attitude” or abrasiveness. And the defendants, in return, showed no disrespect, and certainly no threat of violence. In fact there existed a certain level of trust and cooperation – even if it was simply functional. The men expressed their humanity and dignity to each other. For me the exchange was a sign of the kingdom, a sign of what’s possible. They were not engaged in battle, but kind to each other. War between groups or persons is not permanent or inevitable. “A new heaven and a new earth” is God’s plan, and it is emerging in our presence by the activity of the Holy Spirit.

For these reasons I looked at the exchange between each defendant and the M.P. with delightful amazement. Both parties were agreeable and pleasant. Whatever needed to be clarified or arranged among them appeared to have worked out. I did not notice any tension or ambivalence in them. The M.P. did not approach the defendants with any sign of “attitude” or abrasiveness. And the defendants, in return, showed no disrespect, and certainly no threat of violence. In fact there existed a certain level of trust and cooperation – even if it was simply functional. The men expressed their humanity and dignity to each other. For me the exchange was a sign of the kingdom, a sign of what’s possible. They were not engaged in battle, but kind to each other. War between groups or persons is not permanent or inevitable. “A new heaven and a new earth” is God’s plan, and it is emerging in our presence by the activity of the Holy Spirit.

Now 3:00 a.m., the soldier strongly identified with this hopeful story and shared one of her own. Characterizing herself as a “lover of history,” she described the Christmas Truce of 1914 (featured in the 2005 French film Joyeux Noël). German and British soldiers, on the frontlines of World War I, spent Christmas with each other, and then couldn’t fire on each other the next day, she explained. What began as separate caroling in each side’s trench cautiously merged into a joint celebration of Christmas. It was another expression of shared humanity amid the horror of war. “That one night could have ended the whole war,” the soldier said.

Perhaps she and I also participate in this “story of peace” and shared humanity. Over the years I have advocated for the closure of the Guantánamo prison (as my favorite bright-orange t-shirt declares) and for U.S. detention and interrogation policies to conform to basic fairness. Beyond her name I don’t know much about the soldier that I talked with at three o’clock in the morning, but I do know that her job is to assist in the continuing operation of the military commissions, which I reject. But we do not reject each other as persons. We recognize our shared humanity. I witnessed this, however briefly, between the 9/11 defendants and the M.P. And it is my hope that, however heinous the crime, the family members of 9/11 victims and the 9/11 defendants will likewise recognize dignity and humanity in each other.

Luke Hansen, S.J.

Thanks you, Luke, for this very moving recounting of what has to be a very confusing setting. It's always difficult for me to see through rigid procedural situations to what is really going on.