Family in Flight

Family life in antiquity was a life of insecurity, though families in many parts of the world still know this insecurity well even today. The warm pictures we might concoct of ancient families—though certainly the ancients loved their children, and spouses loved each other just as families do today—was leavened with something modern Westerners do not know as intimately as our ancestors did even two generations ago. Death was always lurking, threatening the fabric and integrity of the family.

Infant mortality in the Mediterra-nean world was high; perhaps as many as 50 percent of children in the ancient world did not live to see their fifth birthday. We should not forget that maternal mortality was almost as high at childbirth, due to complications in pregnancy, poor medical standards and hygiene, subsequent infections and the young age, from our perspective, at which so many mothers, girls or teenagers gave birth.

But this was not the only threat to the family. In addition to the constant possibility of death were the realities of food insecurity, often due to lack of sufficient work, especially for day laborers in Jesus’ day. Unless one was among the wealthy few who could purchase whatever they needed when they needed it—which in the first century was a distinct minority of people—or store up food to compensate for poor harvests or famine, food was something that people needed to purchase daily or lacked daily. The stress this put on parents and children was immense.

Families in antiquity were also strictly hierarchical. The father in the Roman family, the paterfamilias, wielded almost unlimited power over the life and death of his children. The patria potestas, the authority of the father, was not just theoretical power. While Jewish and Greek fathers had less power than a Roman father, the authority of the father was unquestioned. There is, finally, the fact that slaves, who might have amounted to 30 percent to 40 percent of people in the ancient Mediterranean world, could not form legal families. Slave families that had been formed on a de facto basis could be destroyed by the selling of a child or parent whenever a slave owner chose.

These issues are important if we want to see the family into which Jesus was born in its context. For one thing, the fact that Jesus was born and survived and that his mother gave birth and survived would have been cause for celebration in the broader family and kinship network. Surviving birth was not to be taken for granted. The fact that Joseph took Mary as his wife, though he was not the father of the child, was an act of compassion that would not have been expected of any man in antiquity. Matthew’s Gospel tells us that Joseph received revelatory guidance, but it was guidance to care for the most vulnerable of people: a young, unmarried pregnant woman.

And still, the story of the holy family brings into play yet another, broader level of insecurity: political insecurity at the hands of an ancient ruler. The conception of human rights as we envisage them did not exist, and the judicial system would have had little impact if the king decided to kill you. The Holy Family had to make a decision to flee to save itself. Conceptions of justice did exist in the ancient world, but depending upon your status and position, access to such power was absent or extremely minimal. If the king wanted you dead, your death was imminent.

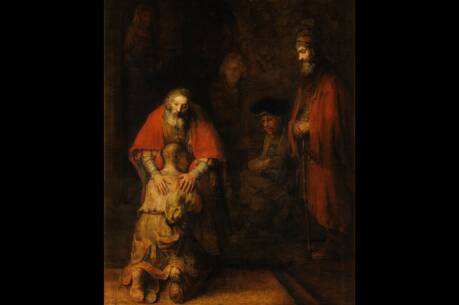

The family life of the Holy Family resonates today, not because of ancient hierarchical conceptions of family, in which strict subordination of the lesser to the greater within the family mimicked the social structure of the day, but because whatever threats challenged the family and whatever the construction of the ancient family, people did love one another and cared for one another no matter the circumstances. The Holy Family is a model of a family sticking together as refugees, with internal tension and external threats and insecurity challenging them at every step of the way. In the same way God protected and sustained them, we need to reach out to vulnerable families today, who model how God chose to send his son to us: in the midst of the human family.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Family in Flight,” in the December 23-30, 2013, issue.