Saints Among Us

Robert Bartlett titles and commences his magisterial work on saints and worshippers with a quote from St. Augustine’s City of God: “Why can the dead do such great things?” For 21st-century readers, living in a time in which David Hume’s skeptical critique of miracles may speak more convincingly than does Augustine’s affirmatory exclamation, Bartlett’s study will be a fascinating and illuminating read. Even for some Catholics, the practices and beliefs that Bartlett describes might seem outside the scope of contemporary experience. But Bartlett’s book will also be welcome to those who have experienced something of the power of the cult of the saints in their own time and place.

Poring over Bartlett’s book, I recalled participating in the vigil of the feast of Our Lady of Lourdes at the eponymous parish in Toronto, Ontario. Hundreds of parishioners fingered rosary beads, praying in unison as we circumambulated the church in the frozen night, marking off a sacred space in the middle of the city. Until I had experienced and been moved by it, I had not associated this kind of devotion or spectacle with the contemporary practice of Catholicism in the United States or Canada. And yet it exists, in some cases with a vibrancy and vivacity that might rival its expression in the period that Bartlett describes.

Sometimes the laity desired more personal access to the saints; one way to do this was to snatch bits of a saint’s clothing, hair or body.

While the proportions of Bartlett’s book are daunting, his style balances rigor and a near-encyclopedic breadth with accessibility and humor. These traits do not always go hand-in-hand, though they do here. Approaching the subject chronologically as well as thematically, Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things? will remain a classic study of the saints, their cults and the faithful for a long time.

Bartlett examines myriad examples of the interactions between the saints, living and dead, and the faithful. A handful will have to suffice here.

It is well known that the faithful often travelled on pilgrimage to encounter the saints; many Christians do this today too. Neither were the bodies of the saints stationary. Sometimes a saint would be translated to a place of greater honor. Translations gave the faithful greater access to the saints through their relics, which were on display as part of the celebration. Disturbing the saint had to be done with care, because even a pious disruption could result in a display of the saint’s power. In some cases, the saint refused to be moved until certain conditions were met. The relics of St. Margaret of Scotland, for example, could not be budged until the body of her husband, King Malcolm, was brought to join her in the new chapel constructed after her canonization in the mid-13th century.

Relics of the saints conferred prestige and honor upon a church. The lure of this prestige and the desire to benefit from a saint’s intercession meant that relics were sometimes stolen. Perhaps surprisingly, these thefts were not always considered impious. In the ninth century, one abbot in Aquitaine gained a reputation for arranging the thefts of relics so they could become part of his abbey’s collection. When the abbot conspired to wrest the body of St. Bibianus (or Vivianus) from a nearby town, one of his co-conspirators feigned demonic possession in order to gain access to the church and the saint on reasonable pretenses. The abbot was proud of his accomplishments in relocating the saint, which he characterized as “a happy sacrilege.”

Monks and clerics in possession of stolen relics often sought to emphasize the neglect the saint had suffered in her previous location, arguing that she was more content in her new home. In an account of the theft of the relics of St. Auctor that were taken from Trier and brought to the church of St. Giles in Brunswick, the Saxon noblewomen Gertrude of Brunswick was visited by the saint himself, who claimed that he was treated without reverence or respect in Trier. The saint purportedly led Gertrude to his tomb, permitted her to take his remains and bring them to a new church and aided her in evading capture for the theft.

Sometimes the laity desired more personal access to the saints; one way to do this was to snatch bits of a saint’s clothing, hair or body. After Bishop Caesarius of Arles died in 542, the congregation there tore off his clothes as contact relics, which the local clergy struggled to recover. In the 14th century, a desire to be in contact with the saints extended beyond the bounds of orthodox Catholicism to communities of men and women in the south of France known as Beguins. A number of Beguins were burned at the stake as heretics in 1321 at Lunel. Some considered these men and women martyrs and divided the bodies of the executed to keep their remains as relics.

In the case of Peter of John Olivi (d. 1298), a Franciscan theologian whose writings inspired these southern French Beguins, a full-fledged—albeit unauthorized—cult developed at his tomb in Narbonne and remained active until Olivi’s bones were exhumed and scattered and the ex votos offered in thanks had been destroyed. The physical remains of the deceased and the site of the tomb featured prominently in the veneration of the saints during the Middle Ages; eliminating these was one way to discourage or even destroy an unauthorized cult.

Relics of the saints conferred prestige and honor upon a church. The lure of this prestige and the desire to benefit from a saint’s intercession meant that relics were sometimes stolen.

Within Christianity, the cult of the saints developed out of the cult of the martyrs. Although the Christian cult of the saints had similarities with the worship of Greek and Roman deities and heroes, critical differences separated them—most important, the Christian rejection of animal sacrifice as fitting tribute to God and his saints. Parallels exist, too, with Judaism and Islam. Here as well, though, important distinctions separate Christian understandings and attitudes toward those recognized as saints from those of Jews and Muslims. These distinctions are rooted primarily in the Christian preoccupation with the bodies of the saints and the movement of the bodies of the “very special dead,” as Peter Brown has called them, from spaces designated for the dead to spaces designated not only for the living, both public and private, but also to spaces designated for worship of the divine—spaces that, in Jewish and Islamic practice (as well as in Greek and Roman practice), would be defiled by the presence of human remains.

Early on, the martyrs and saints were recognized by public acclamation. That is, a group of people—perhaps even those who had known the holy man or woman during this life—attested to the sanctity of the deceased and began to venerate him or her as a saint. By the late 12th century, Pope Alexander III declared that Christians could not venerate saints unless the Roman church had officially recognized them as saints. By the mid-13th century, Pope Innocent IV pronounced that only the bishop of Rome could canonize saints. This understanding of sanctity reflects a Western Christian outlook; without a centralized hierarchy, Greek Christendom and Eastern Christian traditions did not develop a controlled process of canonization. Nonetheless, despite efforts on the part of medieval pontiffs to dictate those officially recognized as saints by the Roman Church, in the later Middle Ages hundreds of men and women were still recognized as saints by public acclamation. Likewise, among some Catholics today, men and women, including the martyred Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero, and the co-founders of the Catholic Worker movement, Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, are considered saints without having received official recognition from the Vatican.

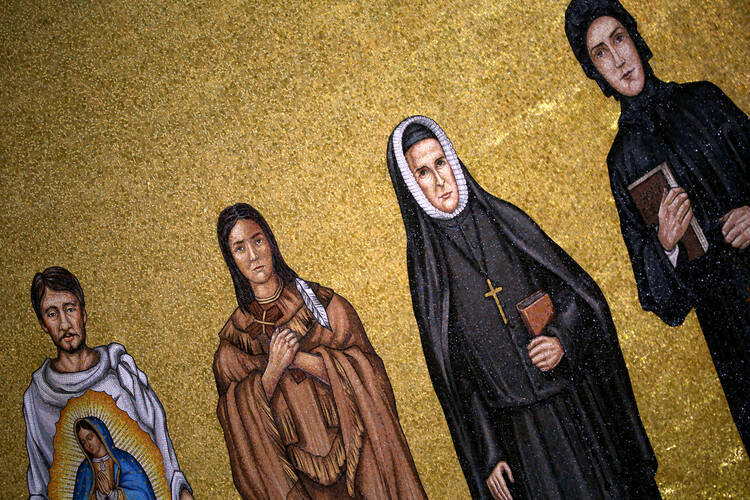

Bartlett’s account of the intimate connections among the living and the dead, the saintly departed and the saints among us, bring to mind the tapestries designed by John Nava for the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles, Calif. In the series of tapestries entitled “The Communion of the Saints,” the artist depicts contemporary Catholics standing together in prayer intermingled with saints from across the ages. The tapestries simultaneously celebrate and complicate our understanding of sanctity; the work of art powerfully argues not only that the saints look like us, in all our diversity, but also that there are saints among us today.

Robert Bartlett’s masterpiece, Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things? brings us back to the sacred (and sometimes profane) origins behind Nava’s moving work of art, so we can develop a better understanding of the saints, their cults and those who have venerated them in the past even as we continue to develop our understanding of the body of Christ among us today.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Saints Among Us,” in the September 15, 2014, issue.