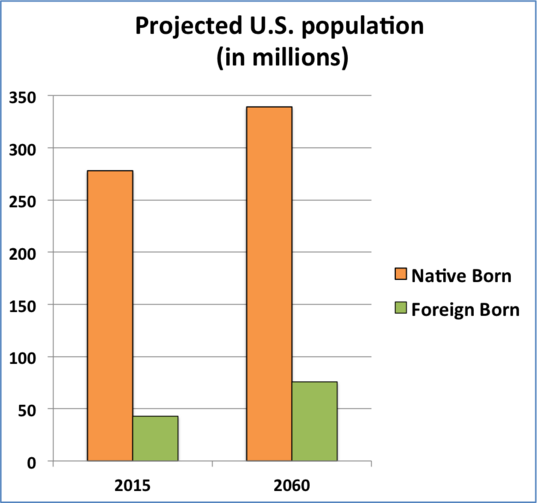

By 2060, the foreign-born will make up 18.8 percent of the U.S. population, up from next year’s 13.5 percent, according to new estimates by the Census Bureau. Up to now, the highest percentage of total residents who were foreign-born was 14.8 percent, in 1890.

The Census Bureau predicts the total U.S. population for 2060 will be 416 million, up from today’s 321 million. Immigration, which will account for 47 percent of population growth next year, will account for 82 percent of growth by 2015, as the number of births flattens out. Without immigrants, America would become top-heavy with retirees complaining about understaffed Walmarts and hospitals.

A bigger and more diverse nation could put new strains on a political system devised for just under 4 million (most of whom had no right to vote). A possible warning sign: We seem to be getting too big for that most iconic of American institutions, McDonald’s, facing a decline in sales as it tries to appeal to a less hamburger-happy nation. If McDonald’s has hit a wall, we can’t assume that any institution is safe. Some questions:

• Can our rigid two-party system survive a growing electorate—and how far will the Democrats and Republicans go to preserve their duopoly?

• Can any candidate win more than a slight majority of this growing electorate? No candidate has won more than 53 percent since the number of voters in a presidential election first passed 100 million in 1992.

• Is there a limit on how many constituents can reasonably fit into a congressional district? Political analyst Sean Trende, arguing for the first expansion of the House of Representatives since 1912, writes, “Today a representative answers to over 700,000 constituents, well over 10 times the number of constituents deemed appropriate by the First Congress.” If the Census projections are correct, and the U.S. population increases by 30 percent by 2060, each member of the House would represent more than 900,000 constituents. Because gerrymandering ensures that most districts are heavily weighted toward one or the other major parties, that means an ever-growing number of Americans stuck in districts where they’re perpetually on the losing side of elections. How will that affect people’s views of the legitimacy of Congress?

• How far apart can states drift in terms of demography and political views before they find it impossible to cooperate on national issues? The Census projections on the foreign-born population mask wide variations among states (the agency does not make state-level projections). In 2012, the foreign-born made up more than 20 percent of the population in California, New Jersey and New York but less than 3 percent in Mississippi, Montana and West Virginia. These states may have radically different views toward the foreign-born, making any kind of consensus for immigration policy impossible.

• Similarly, America’s growing population will not be evenly distributed. Some states will become almost entirely urbanized, while others will remain predominantly exurban and rural. Can they reach a consensus on federal spending priorities and on the best way to provide health care and education?

• The likely concentration of population growth in major urban areas, including several in the South, will also make the U.S. Senate even less representative of the total population. Currently, California has 66 times the population of Wyoming but both states have the same voting power in the Senate, and political scientist Larry Sabato writes, “Just 16 percent of the U.S. population elects fully half of the Senate. When you take into account the 60-vote requirement for many critical pieces of legislation, a mere 11 percent of America’s population elects the 41 senators needed to stop action.” Is there an imbalance big enough for California, or Texas, to demand reform?