It is 5:30 a.m., June 1995, as the rising sun breaks into my little backstreet hotel room in Hanoi, and the light trampling of hundreds of feet padding past my window shakes me out of bed and into my shorts and sneakers to join the multitude of morning runners. The mass is heading toward West Lake, the largest of the city’s more than 16 bodies of water, a park where elders do their morning t’ai chi in unison. Just across the road is the tiny Truc Bach Lake, into which the wounded Lt. Cmdr. John McCain parachuted on Oct. 26, 1967. Not far off is the prison known as the Hanoi Hilton, where he was imprisoned, which is now being converted by foreign investors into apartments and shops. Four smiling students stop me to talk. What was I doing here? I had come to see them.

Hanoi, bustling to rebuild itself, is a beautiful little city, with tree-lined streets, more bicycles than cars and few traffic lights. Its spiritual center is Hoan Liern Lake, where in the 15th century the Golden Turtle God is said to have taken back the magic sword that was given to the emperor to drive the Chinese from Vietnam. Nearby hundreds line up to view the corpse of Ho Chi Minh laid out in his mausoleum, a small air-conditioned house, for 20 seconds of admiration. He had asked that his ashes be planted throughout the country in quiet tree groves where a traveler could find peace.

Vietnam 1975: Enemy at the Gates

The Paris Peace Accords, signed on Jan. 27, 1973, required the United States to withdraw their combat troops from South Vietnam within 60 days. The reunification of Vietnam was to be carried out by peaceful means. Only the U.S. Marine Corps security guards at the Saigon Embassy and some consulates in provincial capitals were allowed to remain. In late 1974 the North Vietnamese broke the truce and under Gen. Van Tien Dung began to push south. Meeting little resistance, they took Hue and Da Nang, a coastal town where American soldiers had once enjoyed the beach. Thousands of South Vietnamese soldiers surrendered or deserted and joined the mass exodus of 300,000 refugees fleeing toward Saigon. The Central Intelligence Agency had predicted that the Southern forces could hold out through 1976, but they were very wrong. The North was determined to hit Saigon in time to celebrate the birthday of the late Ho Chi Minh, born on May 19, 1890.

Meanwhile, in Saigon, the embassy staff was haunted by memories of the Tet offensive in 1968, which demonstrated the unreadiness of the Saigon military establishment, including those stationed at the embassy. In the early morning of Jan. 30, 1968, a 19-man Vietcong team blew a hole in the wall near the embassy and charged through. For six hours the Marine guards held them off until Marines landed from helicopters on the roof and killed or captured the invaders. Maj. James Kean, 33, commander of the last Marine contingent stationed at the embassy in 1975, was determined that lack of preparation would never allow anything like this again. But he would soon face the most challenging situation of his military career.

Up to the final weeks, U.S. Ambassador Graham A. Martin believed that because the North would need American financial aid to reconstruct Vietnamese society, the United States could negotiate a new settlement that might preserve some autonomy for Saigon and the Mekong Delta. To pull this off, he supported a quick coup: Gen. Duong Van Minh was made president of South Vietnam, pushing aside President Nguyen Van Thieu, who, in the opinion of some Americans, had taken kleptocracy to new heights and should have been removed long before. In a tearful televised resignation on April 21, the deposed President Thieu denounced the United States for betraying the South. By April 27 Gen. Dung moved 100,000 troops around the city. Its fate was sealed.

The official evacuation, which should have been planned and executed months before, took place on the two last days; but in various ways, some secret, the exodus had been in process for several weeks. The moral and legal aspects of the daily decisions concerned who must go and when; to whom the United States owed protection; and among them, who had priority. Troops, of course. Civilian employees? Friends of troops and business associates? Wives, of course. Girlfriends? Children, yes. Both those with married parents and the offspring of G.I. nighttime excursions? Orphans?

Many American organizations closed shop and left without their Vietnamese employees. Some, like Northrop Grumman, offered to save local workers—but not their families. Some branches of American banks sent their records and American employees home, leaving thousands of Vietnamese depositors unpaid. A select few had access to a semisecret airlift. Several escape plans were considered hypothetically: boats on the Saigon River could make their way out to the ocean, where the American fleet was waiting; commercial airlines could fly them out; truck convoys, etc. But in the end there was only one hope—a fleet of helicopters to lift them up from the embassy property and fly them to aircraft carriers off shore.

Malcolm Browne, a reporter for The New York Times, wrote that there were also secret heroes who stayed. One was a Vietnamese reporter and photographer for The Times, Nguyen Ngoc Luong. Mr. Browne spoke with another who explained, “In the end the color of the skin counts for more than politics. Anyone who has lived in either the United States or Vietnam knows this, and I have done both. The Vietcong, like me, are yellow.” Mr. Browne compared the Vietnamese-American relationship to a “failed marriage.” And he concludes that “for millions of Vietnamese and not a few Americans the dominant memory will be sorrow and betrayal and guilt.”

Saigon 1995: A ‘New’ Vietnam

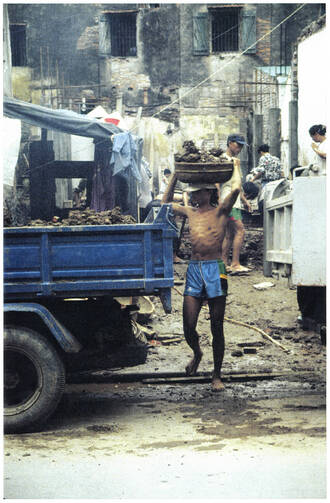

In Ho Chi Minh City, which during my visit I still insist on calling Saigon, Vietnam is poised on the threshold of becoming something very different. Its identity had been in the land, rural hamlets, rice paddies where peasants and water buffalos seemed to work as co-equals. Amid Southeast Asia’s economic boom, Communist Vietnam had decided to fight its way out of poverty by imitating Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, opening itself to foreign investment.

The “new” embassy, which had been opened in 1967, wasstill a government building encased in a concrete shield. Reunification Hall, once known as Independence Hall or the Presidential Palace, stands at the end of a long boulevard. Tourists wandered its halls, decorated with modern art, and visited the Dragon’s Head presidential receiving room, where the chair facing the president’s desk has ornate dragons carved in the arms; in the basement were the bomb-shelter rooms where the leadership could cower. On the day the city fell, the tank leading the attacking army crashed through the iron gates and a soldier ran up the steps to unfurl the Vietcong flag from the fourth-floor balcony. That same tank guards the front gate today.

I stay at the Caravelle Hotel, a hangout where in years past American journalists—Walter Cronkite, Peter Kalisher, Eric Sevareid, Dan Rather and others—would meet at the ninth-floor bar while thumps and booms from distant mortar firing punctuated their analyses of the day’s fighting. A few blocks away are the twin spires of Notre Dame Cathedral, where during my visit the body of Paul Nguyen Van Binh, the 84-year-old archbishop, lies for five days of mourning. A disfigured woman, a leper, cowers at the cathedral door. A local priest explains to me that for the good of the country, the church cooperates with the government, and the churches are filled, even for weekday Masses.

The Last Days: April 29-30, 1975

While General Dung had decided to take the city with its buildings intact and, as far as possible, without killing civilians, opinion at the embassy was divided. Ambassador Martin and his young staff were convinced that they could negotiate more time with the Vietcong; others shared Major Kean’s conviction that Martin was delusional. The ambassador had never recovered fully from his bout with pneumonia and old injuries from a car accident. Once a lively conversationalist, he had become surly; tall, he became stooped, a cigarette perpetually dangling from his lips. Did he cling to the possibility of a negotiated peace because he had lost a nephew in this war? Though he had arranged the early escape of his wife, he would cling to his office until President Gerald Ford personally ordered him to leave.

As if to express distant confidence in the mission, Marine headquarters had recently ordered two new young troops to duty in Saigon: Lance Cpl. Darwin Judge, 18, and Cpl. Charles McMahon, 21, fresh from Quantico, Va. Major Kean added the “newbies” to his battalion with paternal affection but wondered why inexperienced men had been sent to die for a lost cause. This was, in his mind, no longer America’s war but a civil war the South was doomed to lose. At a meeting a visiting C.I.A. officer had informed the men that Saigon would fall soon. When the guest left the room Major Kean looked his men in the face and told them, he did not know what or when it was “coming over those walls,” but “we will not only fight like Marines; if we have to, we will die like Marines.”

In the last week of April the smooth-faced McMahon, the Massachusetts Boys Club Boy of the Year, and the Iowa Eagle Scout Judge were assigned to a guard post on the airport road. In the early hour of April 29, rockets crashed into the compound, knocking a sergeant out of bed. He ran out into the smoke, checking for damage, and found a smoldering hole where the young men’s post had been. A torso without arms lay in the road; another rocket knocked the sergeant into a ditch near flaming motorbikes piled up over the body of Lance Cpl. Judge. The siege had killed its first victims.

Sgt. Mike Sullivan tried everything to avoid being drafted into the Army until, after two years in a community college, he was rescued from the draft by a Marine recruiter. In 1967 he landed in Da Nang, with specialty communications, which meant laying wire lines. But he cherished his intellectual independence and, much to the displeasure of his superiors, read The New York Times, which his mother mailed him. In Vietnam he did not like what he saw. Why were we still here?

On the fatal day he stood on the embassy roof and looked across town to where the Newport Bridge crossed the Saigon River, where the National Liberation Front had planted its flag, just a half-hour drive to the Presidential Palace. Five weeks earlier, he had flown his new wife, Camy Mohegri, to his family in Tacoma, Wash., having been warned by a trusted friend to get her out of the country, fast.

In Washington, D.C., Col. Douglas Dillard, a much-decorated hero from World War II and Korea, had recently returned from a mission to Vietnam to undo some of the harm Operation Phoenix had caused. He knew that the United States had tragically underestimated the broad support for General Dung’s advancing army. He had many friends in Saigon, especially in the intelligence community, so he sponsored three Vietnamese families, one with 11 children. Two families made it to the United States and, with his help, got homes and jobs; the third family all committed suicide in Saigon. Today he sees the Vietnam story played out again in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria: America loses its credibility when it fails to give our allies the support they need.

At the signal—Bing Crosby singing “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas” on the U.S. radio station—Americans knew they must leave immediately. The Chicago Daily News correspondent Bob Tamarkin, writing from the U.S.S. Okinawa, pulled together an hour-by-hour diary of April 29, beginning with the tearful, shirtless Capt. Stuart Harrington, who could not accept that hundreds of Vietnamese in the embassy compound and thousands of others who had been promised evacuation had been left behind. A wild wave of thousands swarmed around the compound, trying to scale the wall. Some, helped up by a soldier or friend, succeeded; others were beaten down. One official pointed his pistol in the face of a boy and shouted, “Get down, you bastard, or I’ll blow your head off. Get down!” Marines smashed the fingers of climbers with their rifle butts. Most of those to be evacuated legitimately were ignored as Marines randomly pulled people up. That is how Bob Tamarkin got in at 5:39 p.m.

At 6 p.m., in a rampage of looting, hundreds stormed the storerooms, food lockers and embassy restaurant for soft drinks, frozen foods, canned goods and cigarettes. Some Marines fought them; some stuffed cartons into their own knapsacks.

At 9:40 p.m. the grim-faced Ambassador Martin examined the pillage, returned to his office and burned documents preserved since the embassy opened in 1954.

At 11:30 p.m., 12 hours after the evacuation began, the Marines rounded up the remaining Americans and got them to the landing pad. Helicopters that normally hold 50 were packed with 80 or 90. With 80 helicopters flying 495 sorties, 70,000 people had been saved.

At midnight helicopters began leaving from both the roof and courtyard as security people went through the rooms destroying anything that might help the invaders. Meanwhile Ambassador Martin, in shirtsleeves in his office, calmly went over details with his staff. At 4:30 a.m. they took off, on their way to the U.S.S. Blue Ridge, flagship of the Seventh Fleet, ending U.S. official presence in Vietnam. At 5:15 a.m. the order came from President Ford to stop all evacuations immediately. At 5:30 a.m. the last scheduled helicopter took off with the remaining Marines and the press, while hundreds of Vietnamese looked up, concludes Mr. Tamarkin’s account, waiting for the next one—that never came.

But something was wrong. Major Kean and his 11 most dedicated men, including Sergeant Sullivan, stood alone on the roof in the silent dawn. Was it possible that they had been forgotten? “It is possible,” Major Kean replied. Then at 7:38 a.m., 23 hours after Major Kean learned that his wife was pregnant, a slender white contrail appeared in the sky far to the southeast. A CH-46 transport helicopter, escorted by four Cobra gunships, was coming for them. Minutes later, as they flew out over the city, they looked down the boulevard to see a half dozen Russian-made tanks lumbering over the Newport Bridge, heading toward the big iron gates of the Presidential Palace.