A church of the pure or a fisherman's trap, that is to say, a net containing a mixture of good and bad fish, according to an expression of St. Augustine? This is the question that comes to mind as my guests arrive: Cardinal Christoph Schönborn and his Dominican brother Jean-Miguel Garrigues. I welcome them into my office, which is decorated predominantly in white, the characteristic color of the sons of St. Dominic. The Dominicans and the Jesuits have often been depicted together, but generally in conflict. History can be unmerciful. But it is also true that there is a deep affinity between them, in the sense that more than one member of the two respective orders, Pope Francis himself among others, have, at some point in their experience of discerning a personal vocation, been faced with the option of choosing between the roads of St. Ignatius and St. Dominic.

During our conversation about the church, and about the times we live in, with the difficulties and challenges that lie ahead, a sense of comfort and confidence prevails. The cardinal and the professor reveal in their conversation a sharp intellectual perception and a zeal for pastoral care. Both, in different ways, have fully experienced these two dimensions. The first as archbishop of Vienna, and the second as co-founder, with other brothers, of monastic fraternities in parishes of the dioceses of Aix-en-Provence and Lyon. Cardinal Schönborn introduced me to his brother, friend and fellow student, and then allowed me to speak with him.

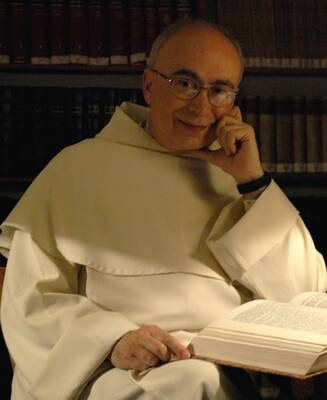

Father Jean-Miguel Garrigues' very name, taken together with his perfect Italian, hints at a variety of cultural and geographical roots. He was born in Istanbul in 1944 in a family of Spanish diplomats. He joined the French Dominicans in 1963. He studied at Le Saulchoir for his licenciate in Philosophy and Theology. Ordained a priest, he spent a year studying at the Orthodox Theological Faculty of Thessalonica, and he then went to the Institute de Paris, where he defended a doctoral thesis on Maximus the Confessor. As Professor of Theology, he took on various functions. It should be recalled that between 1989 and 1992 he assisted, in his expert capacity, the present day Cardinal Schönborn in drafting the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

From 2000 to 2014, he participated under the direction of the Dominican Cardinals Cottier and Schönborn, in the dialogue between Catholics and a group of Messianic Jews. He currently teaches patristic and dogmatic theology at the Thomas Aquinas Institute as well as at the Study House for Dominican brothers in Toulouse, and at the seminary of Ars. He thus lives near the tomb of St. Thomas and teaches in a prestigious center of Thomistic studies. He has published about 20 books relating to dogma, patristics, ecumenism and political theology. Many of his articles have appeared in journals such as la Revue Thomiste, La Nouvelle Revue Théologique, Nova et Vetera and Communio. Since 2005 he has been a corresponding member of the Pontifical Academy of Theology in Rome.

Father Garrigues immediately expresses his sympathy for the tradition of the Jesuits: "I am tremendously indebted to Father Henri de Lubac,” he said. “I was able to meet him in Paris in the seventies, thanks to his friendship with the Dominican who directed my doctoral thesis, Father Marie-Joseph Le Guillou. I recently had the great joy of writing a long introduction to the volume of de Lubac's complete works, which includes his correspondence with Jacques Maritain, whom I also met, in Toulouse, in the last year of his life. For me, Maritain was truly an intellectual and spiritual master."

What about the historically well known theological differences between the Dominicans and the Jesuits?

This conflict is the result of a diabolical maneuver to deprive the church of the fruits of complementarity between our respective charisms. We Dominicans are an order of preachers, our concern is above all to present accurately God's Word and His sacred teaching or “Sacra Doctrina.” And in turn, you, the Jesuits, as missionaries and educators in the broadest sense of the term, you are eager to help souls receive this same Word. Our respective charisms are thus situated at the two opposite and complementary poles of the same mysterious communication of the Word of God.

And so you are familiar with the mystical spirituality of the Jesuits and the Spiritual Exercises?

It was in reading Maritain that I was introduced to the mystical writings of Lallemand, Surin and de Caussade.

But these are precisely the favorite authors of Pope Francis! Some writers claim that the Holy Father is administering the Spiritual Exercises to the present-day church. What do you think?

What better gift could we hope to receive from a son of St. Ignatius of Loyola, who is the author of the Spiritual Exercises? You are quite right: the Holy Father is in the process of once again placing believers face to face with the practical requirements, that is to say, the theological and evangelical requirements, of their faith. He is indeed leading us into the practice of the "spiritual exercises." And let us not be surprised: these exercises can be quite disturbing for a certain form of spiritual comfort which at times blithely mixes together, in a seemingly pleasant spirit of worldliness, correct and rather rigid opinions with self-satisfaction and a tendency to complacently judge others. There are, of course, on the other hand, those who enthusiastically applaud the pope only because they hope that the discernment of spirits that he has undertaken will end up bringing Catholics back to subjectivism and moral relativism. But let them not rejoice too soon! It was precisely these excesses which required, starting in the late 1970s, that John Paul II and Benedict XVI restate once again the fundamental elements of the faith against those who falsely interpreted Vatican II in terms of a rupture with tradition. If Pope Francis can refer today to an evangelical renewal of the church, it is because we have now been reminded of the fundamental aspects of the faith that were threatened by false relativistic interpretation of the spirit of the council. Keep in mind that among the most cherished friends of the new pope, there are many evangelical Christians, such as the pastors whom he loves to visit, and whom no one can accuse of biblical liberalism or moral laxity, quite the contrary.

And so Pope Francis is a pontiff in line with the authentic tradition?

By leaning with compassion over those who have been wounded in their family life, the pope actually seems to be reconnecting with an ancient Roman tradition of ecclesiastical mercy towards sinners. The Church of Rome, which from the second century onward, inaugurated the practice of penance for sins committed after baptism, almost provoked a schism on the part of the church of North Africa, led by St. Cyprian. The North Africans did not accept the Roman practice of reconciling the lapsi, that is to say, those who in times of persecution had become apostates, and who were, alas, much more numerous than the martyrs. Confronted with the rigorism of the Donatists in the fourth and fifth centuries, and later on with that of the Calvinists and Jansenists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Rome has constantly refused a "church of the pure" in favor of a "reticulum mixtum" that is to say a "mixed fish net" encompassing both the righteous and sinners, according to an image used by St. Augustine in his Psalmus contra partem Donati.

I am very much interested by this reference to ecclesiastical tradition joined to the tradition of the Ignatian charism. It implies an entire vision of the church, don't you think?

Francis has become pope while remaining a Jesuit. He is thus the mature product of a great spiritual tradition that has also fought in favor of this same principle of mercy against the rigorism of the Reformation and the spiritual elitism of the Jansenists. The vision of the church that Francis has, is one of a church for all, because—whether Port Royal likes it or not—Christ died for everyone without exception, and not just for the few. The church is therefore not a select and exclusive club: neither that of a social milieu that is Catholic by tradition, nor even that of people who are capable of virtuous heroism. Working on behalf of this church whose doors are mercifully open, you Jesuits, over a period of three centuries, have won back a large part of Europe, which had gone over to Protestantism. You did it by pastoral work based on mercy, and centered upon the Heart of Jesus, expressed in terms of baroque "theodramatics" and in the pastoral pedagogy of casuistry. The goal has always been to "help souls" in the concrete situation where they find themselves when the Lord calls them.

Mercy and truth, taking into account the factthat the truth "is" mercy …

In a church context, where doctrinal and moral principles have been firmly recalled by the two great pontiffs who preceded him, Pope François is instinctively drawn towards mercy, feeling unable to close his eyes any longer to the distress of so many of his children. At the same time, as we saw during the last Roman Synod of Bishops, Francis is confident that church dynamics will gradually and sometimes laboriously, establish the correct relationship between the fundamental truths of the faith and the need to show pastoral mercy towards persons.

Does it not seem to you that in our ecclesiastical discourse we often tend to speak in ideal terms? This is indeed a good thing because it gives us a vision to which we can refer. But I think we will also need to find the right words for situations that do not fit into this ideal. That which does not correspond to the ideal, does not always have to be judged negatively, but can instead be seen as a possible step forward along the way. My question is this: can we develop some form of graduality? Point No. 11 of the relatio synodi seems to have formulated this idea very well. It constitutes the living heart of the relatio document, the place where it is written that "we must welcome people along with their concrete existence, we must know how to support their quest, encouraging their desire for God and their will to be an integral part of the church. We should do this even among those who have experienced failures, or who currently find themselves in the most disparate situations." What do you think?

I think that if we were to lose the correct understanding of the foundations of the couple and the family, it would be like attempting to move forward without a compass, governed only by a form of emotional compassion, which would be doomed to fall into an unrealistic type of sentimentality. For example, there is no way of getting around the fact that all Christians live under the law of Christ, and that therefore the indissolubly of marriage applies to them all. There is no place for a "graduality of the law," no place for a moral goal or “end” that would vary according to the situation of the subject. However, this truth is in no way denied or played down when we ask people who have failed or who are presently unable to live up to this commandment of Christ, not to add the sin of injustice to the sin of infidelity, for example, by not paying the alimony agreed upon after a civil divorce. As the king of France Louis XV said when he was chided by a courtier for continuing to abstain from meat on Friday, although he had a mistress, "The fact that we are committing one mortal sin does not mean that we should go on to commit a second one." This is where the "law of graduality" comes into play. It invites people who, in fact, are not yet capable of breaking once and for all with a particular sin, to gradually move away from evil by beginning to accomplish the good (still insufficient but real) of which they are capable.

Here we have a form of casuistry which concerns the progressive accomplishment of good and which therefore in no way contradicts the principle according to which the natural law and the law of Christ apply specifically and equally to all Christians.

Does thismean that we should avoid pastoral approaches requiring either "all or nothing"?

That's exactly it. The “all or nothing” approach may seem "safer" to theologians who advocate "tutiorism," but in fact it leads inevitably to a "church of the pure." If we value formal perfection above all else, as an end in itself, we unfortunately run the risk of covering up in actual fact, a great deal of self-righteousness and hypocritical behavior. The sharp discernment of the pope, who is a man of the “spiritual exercises” has inevitably caused him to put his finger directly into this particular wound. Like any good doctor, he prefers taking the risk of causing a little bit of pain, rather than allowing the evil of spiritual pride to fester, hidden under the external appearances of virtue.

We are situated here a long way from relativism. Nonetheless some people today seem to very much fear the danger of a relativistic drift.

The keenly penetrating discernment of the pope concerning the personal dynamics of our human acts must not be banally mistaken for relativism. It would be senseless to confuse the "law of graduality," which encourages the progressive and continually finalized exercise of acts of free will oriented towards virtue, with the subjectivist relativism which is implied in a "graduality of the law." St. John-Paul II's encyclical "Veritatis Splendor"definitively prevented the church from entering into this dead-end. The encyclical did, however, leave wide open the workspace for the prudential exercise of acts of free will by human sinners, who, unless they receive very special graces, are unable to achieve moral goodness all at once.

One can well understand why this pope was so concerned over the rise of individualism and subjectivism in moral matters. In the encyclical "Veritatis Splendor" there are words that need to be understood attentively and wisely.

There is a good example of this in No. 52, where we read: "The negative precepts of the natural law are universally valid, they oblige each and every person, always and in all circumstances. Indeed, they prohibit a specifically determined act semper et pro semper, that is without exception.” St. Thomas, however, distinguishes speculative certitudes and methods, from methods and certitudes in the moral domain. In speculative matters, truth admits no exceptions, either in individual cases or in general principles. But practical reason, that is to say, morality, deals with contingent realities. The general principles are always universal, but the closer one gets to individual, concrete realities, the more one is bound to encounter exceptions. In the same passage of the Summa Theologiae, Thomas goes on to affirm that in such and such a particular case, there can be, exceptionally, modifications of the natural law, due to special causes.

This leads us to the following question: who determines the exceptions? We need to acquire a better understanding; we need clearer images capable of shedding light on our journey.

You mention images, and one such comes to my mind, a picture I find very effective. Please do not smile, but I am thinking of an instrument that has of late become very important to motorists: the GPS navigation device. When we have to go somewhere, we introduce an address into the browser, is that not so?

That's right. But what does the GPS have to do with our subject?

Let me explain. The theoretical premise for the use of this metaphor is that the moral principles concerning the final orientation inherent in human beings are not goals that a person chooses at random. Instead they express the basic orientations of human life, which are intermediate in relation to our ultimate finality that is God himself. The church, through the development of her moral doctrine, discerns these ends in a gradual, consistent and irreversible manner. But these fundamental orientations of human life must take shape concretely in every one of us, in both the order of nature, and of grace. They draw us to God through the exercise of our own personal freedom. If we were to answer perfectly, as did the Blessed Virgin Mary, our life would correspond to the first itinerary proposed by the GPS to reach the indicated address.

My experience, in fact, is that I sometimes take a wrong road, because I did not quite understand the instructions of the GPS, or because I was distracted, or because a road is closed off.

This is exactly what I was going to say. We know that "all have sinned" (Romans 5, 12) and that, as St. Therese of Lisieux said, "we are all capable of anything." We are all sinners and therefore we certainly do not answer as the Virgin Mary did. Now what does the GPS do when we deviate from the route indicated to reach the address? It does not ask us to go back to the starting point and to resume the first itinerary. Instead it immediately proposes an alternative route starting from the situation in which we find ourselves.

Oh yes, now I see what you mean...

That's it: analogously, whenever we go off course because of our sin, God does not ask us to return to our starting point. Indeed, biblical conversion of heart (metanoia) is not a return to the beginning (epistrophe) as is the case in Platonic philosophy. Instead God reorients us toward Himself by tracing for us a new road leading to Him. We should note that, just as the address of the final destination does not change in the GPS, moral ends never change in the divine government. What really does change (and indeed how much so!) is the path followed by each person in his freely undertaken journey towards moral and theological goodnessand ultimately towards God Himself. Think of the number of alternative routes that the divine GPS had to indicate to the good thief before he reached his last and supremely dramatic short cut of the cross.

Thank you for this image which forcefully clarifies matters. Michael Fuller, the theologian and organic chemist, wrote that theologians should be attentive to technological developments in the hope that these can furnish metaphors and analogies capable of nourishing their theological thought. This image of your’s is certainly one of these. In this way you illustrate the value and true meaning of the “law of graduality” as a dynamic of personal conversion, which traces each time, a personal itinerary, but which always remains oriented towards the same moral and theological goals.

As a Jesuit you are well aware of all this. Indeed, the same thing occurs in the exercise of the Ignatian charism of "helping souls," (to employ the expression of St. Ignatius himself). It is this charism of assistance, which is clearly manifested by Pope Francis, in his deeds, his way of being and his words. It strikes me as an excellent way of cooperating with the Providence of the God who meets us continually in our concrete personal situations, both interior and exterior. But, if we lose sight of the merciful way in which God our Father governs and guides us, we end up by disembodying the various moral goals and transforming them into a Platonic set of abstract ideals which no longer take root in our life. We then may go on to defend them, but for mostly non-evangelical motives, like the desire for auto-affirmation (whether of self, or of one's milieu). This goes hand in hand with a tendency to condemn those who are unable to practice these ideas. To act in this way is above all to forget that the morality taught by the church is a practical wisdom that gives life, and not a form ofself-righteousness that procures self-justification at the cost of judging others. If we give in to this temptation, we also run the risk of appearing in the eyes of non-believers, including those who are of good will, as nothing more than a sect with fanatical convictions.

Of course, what you say has consequences and repercussions for Christian life. For example, it has implications for the way of understanding what the Christian witness should be, including the witness given by the ecclesial movements; implications for the shaping of the mission, which needs to avoid the pitfalls of fanaticism.

Very well, let’s start with one consideration: Pope St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, together, the first in a prophetical way, the second in a doctoral way, have given rise to the so-called “WYD generation,” the generation of the World Youth Days. These young people have played a meaningful and active role, serving as a dynamic and significant minority, proposing an alternative to moral relativism and overly permissive behavior in our "post-Christian" societies. However, after the time when the popes encouraged the birth and early growth of this generation, a discernment period has arrived, rendered necessary and sometimes urgently so, by, among other things, various crises that have occurred in some of these movements and communities. Indeed, these young men and women were been born into the post-Christian society, and although they are reacting against it when it comes to things like family morality and respect for life, they also carry within themselves certain traits of the very social situation against which they are protesting. At the very least, these traits can be perceived in an extreme interest in efficiency and visibility, that can lead to conduct that can come off as “spiritual marketing”, a quest for the spectacular, and a cult of youth, that sets itself up in opposition to the previous generation, the one contemporary to Vatican II. This is often done in the name of a certain “traditionalism”, that is, the nostalgia for an ecclesial past, which corresponds more to fantasy than to reality. The Ignatian discernment of Pope Francis could not fail to notice in some of these movements, traits that need to be corrected, precisely in order to prevent the prophetic inspiration of their testimony, which is often admirable and sometimes even heroic, from being surreptitiously short-circuited by non-evangelical motivations. The worst would be to pose arrogantly in front of others as paragons of domestic virtue, while implicitly judging those who are unable to live up to the same standards. The result would be an incapacity to see and appreciate the good elements that are nevertheless present in the lives of these people, and in a failure to help them carry their burden as St. Paul exhorts us to do (Gal 6:2).

However, I have noticed that some voices have been expressing concern about the respect for doctrine. I am referring, for example, to the way in which the synodal discussion was received. I myself took part in the synod and I can attest that never for one moment was doctrine placed into question. Instead, an interesting aspect of the synod was precisely its ability to discuss things freely without "challenging or putting into question." But beyond the debates themselves, which were always free and correct, I note with concern that some people and groups have been expressing themselves with violent accents, aggressively and explosively. One issue that has disturbed some people, for example, is the affirmation that certain humanly good elements can be found even in people who are living in irregular situations.

It is indeed significant that one of the points that caused the most trouble is the affirmation that there may be humanly good elements in people who are living in unions, which are either in no way comparable to marriage, as is the case for homosexual unions, or which realize only partially and imperfectly the requisites of marriage, as in the case of civil unions, or in unions having one or two divorced and remarried partners. Here we can measure the extent to which a certain type of Jansenism is in danger of quietly slipping its way in among the proponents of a "church of the pure."

What would St. Thomas Aquinas have to say about this today ?

For St. Augustine, who was fighting against Pelagianism, people can do nothing good without grace—whether it be in thought, in will, in love or in action. St. Thomas Aquinas on the other hand, although he does agree with Augustine on the impossibility of a morally good life without grace, has a much more nuanced position. He distinguishes the overall morality of a person's existence from the morality of particular acts of that person. In the Treatise on faith of the Summa Theologica, he asks himself whether every act of an infidel is a sin. His answer is based on the case of the centurion Cornelius in Acts 10, 31: "The actions of the infidels are not all sins, but some are good." And he elucidates on this, saying that "mortal sin does not completely ruin the good of nature," and therefore, "the infidel can also do some good, in that which does not relate to his infidelity as a goal." For St. Thomas, even though without grace we can not accomplish "all the good" that is in our nature, which is wounded insomuch as it is no longer ordered to its ultimate goal, we can still accomplish morally good acts in particular domains of our life. But this does not render our life morally good with regard to its personal orientation towards its ultimate end, which is God. This enables us to understand, among other things, the paradox of certain criminals who at times are seen to conduct themselves as good fathers to their families.

We are talking here about what St. Thomas and classical theology call "operating grace" through which God leads the sinner to justification. But of course man can also refuse this grace. We should remember what the Council of Trent says in its decree on justification.

St. Thomas recognizes that justification is not something miraculous and that its preparation can require time and human collaboration. This collaboration is of course not yet meritorious, but it is a form of cooperation with operating grace and works under its motion in order to dispose the soul for justification. Since operating grace takes the initiative and goes out in advance to encounter all men that God wants to save, this preparation for justification incessantly produces good acts, as long as sinners do not refuse to be prepared. It produces these acts relying on all that which is less damaged in our human nature. These good acts are not meritorious because they are not yet done under the inspiration of charity. But through the mercy of God, they succeed in maintaining in existence vast sections of natural good in persons, families and societies.

And so, you maintain that this is the way we ought to understand and explain the affirmation put forward during the Synod of Bishops, and which has caused so much alarm among the advocates of the "all or nothing" approach.

Exactly. The theology of the gradual or progressive preparation for justification, a theology involving what we have called the divine GPS, allows us to give an interpretation of the “law of graduality” which prevents it from being interpreted as a “gradualness of the law” in the perspective of a subjectivist “situation ethic,” a theory that the Magisterium has rejected. This theology also helps us to understand that since the human person is not determined by its conditioning, men and women can respond to the saving grace of Christ, who draws them towards charity, even while they are still in mental and social structures that are imperfect with regard to the truth. People may move toward Christ's salvation by accomplishing a significant share of moral good, while they are in a union which is only imperfectly marital, or even in a radically non-marital union. If people are not sanctified by these unions de facto, they can nevertheless be sanctified in these unions by all the elements therein which predispose them for charity, through the exercise of mutual support and friendship. Those who have had occasion to closely observe civilly remarried divorcees or homosexuals living as couples have often witnessed the way in which these people can give proof of (sometimes heroic) devotion, especially in instances of physical or moral trials. In what way would a denial of these facts help to reinforce our own certitudes and our witness to the truth?

The most important point in what you tell me is that we Catholics, need to find a positive way of putting forward our moral certitudes, instead of concluding things by making a negative judgment, which can slide very easily from the act itself, judged as sinful, to the person who is the author of the act. If we really believe that the path traced for us by the church in the footsteps of Christ, is a path of life and true happiness, our certitude does not need to condemn and repel those who do not share our ideal, or who are unable to live in conformity with it.

Yes indeed, it’s really quite difficult to see how a more compassionate policy of pastoral care for the "weak," can cause couples who are “strong” and sometimes even heroic, to feel that they are being mocked and despised. If this were the case, it would tend to indicate that their virtue is based excessively on self-satisfaction and that it is perhaps therefore nothing more than a "dead work" deprived of charity. On the contrary true charity expresses itself in mercy, by a capacity for accompanying in a brotherly way persons who are still groping along in the dark on the path of life, the capacity of recognizing the part of goodness that remains in these people, the capacity of bearing with them a little bit of their burden. Is this not what Pope Francis is inviting us to do in the famous spiritual exercises, which, as a good Jesuit, he is preaching to us every day?

In the time that separates us from the next synod, we believers must pray so that the church can more fully discern the best way of bearing witness about her certitudes, with rigor in regard to the truth of Christ, but without turning this into rigidity. We must be eager to save those who are lost, and not be exclusively concerned about not losing those who are saved.

Doctrinal rigidity and moral rigorism can lead even theologians to extremist positions that defy not only the sensus fidei of believers, but even simple and plain common sense. A recent newspaper column quotes with praise an American theologian's letter which contains senseless affirmations about the respective gravity of contraception and abortion: “Which is, in this case, the more serious evil? To prevent the conception—and very existence – of a human being with an immortal soul, desired by God and destined for eternal happiness? Or to abort a child in the womb? The latter is certainly a grave evil, "Gaudium et Spes" calls it an ‘abominable crime.’ But a child exists who will live eternally. In the former circumstance a child God intended to be will never exist.” Thus, based on this reasoning, it is claimed that abortion is more acceptable than contraception. Incredible!

Yes, I share your judgment. I read these words too and I was profoundly stunned by their lucid senselessness.

It is no coincidence that such reasoning proceeds from a representative of the hardest line among those who advocate "tutiorism," an opinion, by the way, condemned in 1690 by the Holy Office, and which is today opposed to the more nuanced approach of Pope Francis, who seeks to take into account particular cases. I think that it was this same current that demanded the removal, from the final declaration of the synod on the family in October 2014, of the reference to the "law of graduality.". Indeed, this law must be explained as the graduality of the subject that is, as the gradual, progressive way in which a person learns to practice the requirements of the law, and it must be distinguished from the "gradualness of the law" itself in its specification. But the law of graduality already figured significantly in the post-synodal apostolic exhortation "Familiaris Consortio" (1981) of John Paul II, and it is now put into practice by a majority of confessors and spiritual directors in their pastoral accompaniment of persons whom St. John Paul II liked to refer to "those who have been wounded in life.”

And it seems to me that this reasoning is similar to that of those who were already scandalized when some missionary sisters, exposed in certain regions of the world to the danger of being raped in time of war, were given the authorization to take the contraceptive pill in advance. According to these theologians, every sexual relationship, whatever its circumstances, including rape, must remain open to fertility, since God may wish to bring a new soul to life.

Yes, and these are the same who asked that John Paul II, in his encyclical "Veritatis Splendor" (1993) formulate as a dogma that "killing an innocent person is always a crime, whatever the circumstances of the act." John Paul II did not consent to do this, because an irrevocable dogmatic formula can include neither considerations nor exceptions. Such a definition would at the same time have rendered illegitimate the Catholic doctrine of self-defense, which can sometimes involve the death of innocent people resulting from acts with double effects that may entail collateral damage. It's also the same current that criticized more recently the personal opinion that Benedict XVI expressed in his non-magisterial book The Light of the World (2010). The pope declared: "There may be a basis in the case of some individuals, as perhaps when a male prostitute uses a condom, where this can be a first step in the direction of a moralization, a first assumption of responsibility, on the way toward recovering an awareness that not everything is allowed and that one cannot do whatever one wants." For those who criticized Pope Benedict XVI in this instance, the condom is intrinsically evil, independently of any consideration of the circumstances of its use.

We can perceive the same reaction against any consideration of the circumstances in particular cases, out of a "tutiorist" fear of anything that might seem in the least to weaken obedience to the correct general doctrine ...

It is not permissible in any case whatsoever, under pretext of "tutiorism," to abolish the gradation between various moral faults, simply because they are all mortal sins; and, as we have seen above, when comparing two sins, it is wrong to declare the lesser one more serious than the greater, simply because it is most widespread and can therefore lead to social acceptance of the greater sin. It is a form of "social consequentialism" which is just as bad as the individual "consequentialism" condemned by "Veritatis Splendor." It leads to professing a manifest aberration. No really, it is not the rigid and least merciful position that is the safer one from a moral point of view.

But, according to you, is it likely that the Synod of Bishops could ultimately threaten the Catholic doctrine of marriage and the family, confirmed by John Paul II and Benedict XVI?

This is completely implausible. The pope is clearly seeking to insure that justice is accompanied by a more equitable application, and that firmness with regard the principles goes hand in hand with mercy for people in their particular journey. When St. Thomas, in the treatise on the virtue of justice in the Summa Theologica speaks of equity, he follows Aristotle, calling it epieikia, a word that in the New Testament took on the meaning of “moderation” (cf. Ph 4, 5) and “indulgence” (1 Peter 2: 18). Thomas presents equity as “the most prominent part of legal justice.” Here is how he explains it: “Because the object for which laws are made concerns human acts involving singular, contingent, and infinitely variable cases, it has always been impossible to establish a legal rule that would never be in default. Thus lawmakers, considering what happens in the majority of cases, have passed laws using this as their point of reference. However, in some cases, the observance of such laws can go against the equality of justice and the common good, which is the object of the law.” About these cases Thomas says “the good consists in neglecting the letter of the law, in obedience to the demands of justice and the public good.” It will be up to the Synod and to the Holy Father to determine how far the church can go in its efforts to be of help in special cases of persons whose marriage has been shipwrecked. They must determine how far to go along the lines of an equity, which would become more distinctly epieikeia in the sense given to this term by the New Testament, that is, “indulgence.”

You have long served as priest in a parish, you have this experience. Would you be able to suggest some concrete and specific cases that could perhaps benefit from the distinct equity we have just mentioned?

Yes, I have in mind a de facto couple where one of the members was previously married. The couple has children and they lead an active and recognized Christian life. Now let us imagine that the partner who had been married submitted the previously broken union to an ecclesiastical tribunal but was unable to obtain a declaration of the invalidity, the tribunal having concluded that there was a lack of sufficient evidence. The person remains convinced the marriage was invalid, but does not have the means to prove it. Based on attestations concerning their good faith, their Christian life and their sincere attachment to the church and to the sacrament of marriage, given by an experienced and respected priest who is there spiritual guide, the diocesan bishop could discretely grant them access to the sacraments of penance and the Eucharist without pronouncing a marriage annulment. In doing so, he would be extending, on a one time ad hoc basis, the type of derogation, founded on confidence in the good faith of the persons involved, which the church already grants to divorced couples that promise to live in continence. Note that in the latter case, epieikeia is already at work, because although the practice of continence removes the sin of adultery, it does not suppress the objective contradiction existing between the Eucharist on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the rupture of the previous marriage followed by the formation of a new couple, living with emotional and familial ties.

What other case did you want to present to me?

The other type of situation is undoubtedly more difficult. It is that of a de facto couple where, after divorce and civil remarriage, the divorced partner (or both partners) undergoes conversion to an authentic Christian life, which can be attested to by others, including an expert spiritual father. They believe previous sacramental marriage really is valid and if it were in their power, they would try to repair the rupture, because they are sincerely repentant; but they have children and in addition they do not feel the strength to live in continence. What is to be done in such cases? Are we to demand that they make a promise of continence, which in their case would be presumptuous without a special charism of the Spirit?

In the two cases you have examined, it seems to me that there is no question of bypassing the indissolubility of marriage. On the contrary, in these two specific cases, the persons involved recognize and accept the indissolubility of sacramental marriage and have no contempt for the law. They do not ask the church to recognize their relationship as a marriage, but to allow them to continue in the best way possible their Christian life through a full sacramental life.

For the church it would involve an ad hoc or one-time exception to the traditional discipline, a discipline based on the intense harmony that exists between Eucharist and marriage. The exception would be granted either because of a probable doubt about the validity of sacramental marriage, or because of the de facto impossibility of a return to the status quo of the sacramental marriage prior to the divorce, and that despite the desire to do so.

In both cases, this derogation would be granted in order to favor the practice of a Christian life already firmly established. This epieikeia of indulgence would be along the lines of the oikonomia (economy) of Church Fathers between the first and fifth centuries, before the period when the worldly pressure of the Byzantine emperors caused it to be expanded in the East (at the In trullo council held in the VIIth century) so as to include actual cases of remarriage after divorce.

The cases we are mentioning here are painful but relatively rare. On the other hand, we see numerous cases of couples whose Christian life and religious practice are quite marginal, but who demand with a great deal of fanfare in the media, a change in the church's discipline concerning the divorced and remarried. They are primarily preoccupied with obtaining a social recognition of their new union on the part of the church. They are trying to force her to accept, in one way or another, the principle of remarriage after divorce. To legislate in favor of these people would entail the risk of jeopardizing the meaning of faithful and indissoluble marriage, which so many Christian couples strive to live up to, and not without effort. It would also entail the danger of encouraging another form of the “spiritual worldliness” as the Holy Father has so rightly discerned. I would define it as “religious worldliness.”

So what is the adequate pastoral attitude? How would you characterize it?

"To have a tough mind and a tender heart." This well-known phrase of Jacques Maritain to Jean Cocteau, which haunted the heroic Sophie Scholl in 1943 before her execution in a Nazi prison, comes to my mind concerning the Synod of Bishops. In this regard, I would like to play a little bit with Maritain's metaphor and say in turn to all Catholics: Let us have neither a tough mind with a dry heart, nor a tender heart with a flabby mind. For these two attitudes are now clashing together in a sterile dialectic.

On the other hand, it seems that some people estimate it unnecessary for the synod to recall once again the basic foundations, natural and supernatural, of marriage and the family, the fundamentals which been accepted and taught by the previous Magisterium.

Maybe they consider these things sufficiently well-known or think that in the past they became wearisome through over repetition. But the train of thought that runs through their discourses makes it clear that they really find all these things quite bothersome and “overly theoretical,” fearing that they could stand in the way of the more compassionate and educational attitude of the pastoral approach. For this reason, they are suspected of paving the way for moral relativism by those who support a stricter doctrinal line. But these supporters, in turn, are victims of another fear, dreading that the church might abandon the fundamental truths. In the hazy background of our western societies, these people are afraid that if the magisterium becomes preoccupied by the profusion of borderline cases, there would be a risk of weakening the certainty of the doctrinal principles in the soul of the faithful. For this reason, they too are suspected by the others of falling into an idealistic formalism which is disconnected from real life and human suffering.

At the end of our exchange, we fully agree that the testimony which Christians are called to give is to the God of truth, who is also the Merciful One. “We must pray to the blessed Paul VI,” Fr. Jean-Miguel Garrigues says to me. “May this Blessed Pontiff intercede so that Catholics leave behind this sterile dialectic between their conflicting fears, and move on towards a form of wisdom that is capable of integrating and coordinating all things, assuring that, as the psalm says, ‘love and faithfulness meet; justice and peace exchange a kiss.'”

I have in mind right now the fire of Pentecost, the outpouring of the Spirit that enables us to relive the origins of the church. “The disciples are completely transformed by this outpouring: fear is supplanted by courage, imperviousness gives way to the proclamation,” Pope Francis said after the Regina Caeli on May 24. “Mother Church” continued Pope Francis, “closes her door in the face of no one, no one! Not even to the greatest sinner, to no one! This is through the power, through the grace of the Holy Spirit. Mother Church opens, opens wide her doors to everyone because she is a mother.”