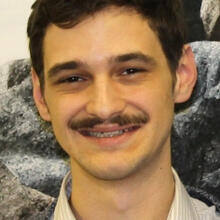

The Toronto-based journalist Desmond Cole, a member of the local chapter of #BlackLivesMatter, has emerged as one of the most important voices in Canadian media on the topic of white supremacy and anti-black racism. In a country known for maple-syrupy trivialities and over-politeness, the idea that the U.S.-based campaign against police brutality could secure or even need a national foothold may come as a surprise. But “anti-black racism doesn't recognize borders,” Mr. Cole says.

Canada is not the United States, but Mr. Cole still sees a country very much a part of a British colonial legacy—with its own history of slavery, its own share of racist policing and its own strange admixture of national pride and self-deception. The mechanics of anti-black racism, he says, are hardly novel.

#BlackLivesMatter began as a recognizably U.S. phenomenon, as it wrestled with its own particular history of racism and policing. But it has found contingents of solidarity across the globe, expressing not only connections among the African diaspora but also exposing the problems of policing and racism outside the United States. Social indicators of systemic racism like disproportionate police shootings and incarceration are not unique to the United States.

In Toronto, the local chapter of #BlackLivesMatter began as a way for black Canadians to demonstrate support for their U.S. neighbors who have been targeted by centuries of sedimented suspicion, but it quickly evolved to publicize eerily similar pathologies in Canadian society. In 2014, Black Lives Matter Toronto made headlines by shutting down a section of Toronto's Allen Expressway for two hours, protesting the deaths of Andrew Loku and Jermaine Carby, both black Canadians shot by Ontario police.

B.L.M.T.O. showed up again at Take Back the Night, a historically feminist march that protests rape culture and sexual violence, drawing attention to anti-black racism and the ongoing crisis of missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada. Protests also included occupying space at the Toronto police headquarters, blocking the entrance to Ontario's Special Investigation Unit and disruptions of town hall meetings.

The group’s provocations came to a head when it halted the movement of Toronto's 2016 Gay Pride parade in a plume of rainbow-colored smoke. B.L.M.T.O. protests certainly gain media attention, but expressing the peculiarly Canadian contours of white racism is more difficult in a society where multiculturalism is often a point of national pride and where only 3 percent of the population is in fact black. As in the United States, black Canadians are disproportionately represented in prisons; one in 10 Canadian inmates is black.

Outside prisons, the controversial Ontario police practice known as “carding” became a central political issue over the last year. Sometimes compared to “stop and frisk” practices in the United States, Ontario police describe carding as an intelligence-gathering method. Responses are retained in a private database. While police defended the carding policy, officially known as the Community Contacts Policy, arguing that it builds knowledge of communities, the practice came under fire for its tendency to stop and question people of color more than white people. The Toronto Starfound that 27 percent of carding incidents targeted black people, who make up 8 percent of Toronto's population.

In a feature in the monthly Toronto Life in 2015, Mr. Cole reports being stopped more than 50 times. Reflecting on the police database where his information is stored, he wonders, “Does it classify me as Black West African or Brown Caribbean? Are there notes about my attitude? Do any of the cops give a reason as to why they stopped me? All I can say for certain is that over the years, I’ve become known to police.”

In 2016, following a year of investigative reporting and protests, Ontario banned random carding. Mr. Cole was not impressed. He considers that gesture a public relations move, not evidence of a systemic change, and he has continued to hold the province accountable in his regular column at The Toronto Star.

Mr. Cole has some blunt counsel for fellow Canadians as they confront the troubling history and contemporary realities brought to light by #BlackLivesMatter chapters: “Stop being racist.” We like to make these things complicated, he says, but the matter is as simple as refusing to accept internalized attitudes that treat people of color with suspicion and as irrelevant members of society. “It's not hard to stand up in solidarity,” Mr. Cole says.