Inspired by rising tensions with North Korea, I have taken to blowing myself up with a nuclear war simulator.

Yes, you read that right.

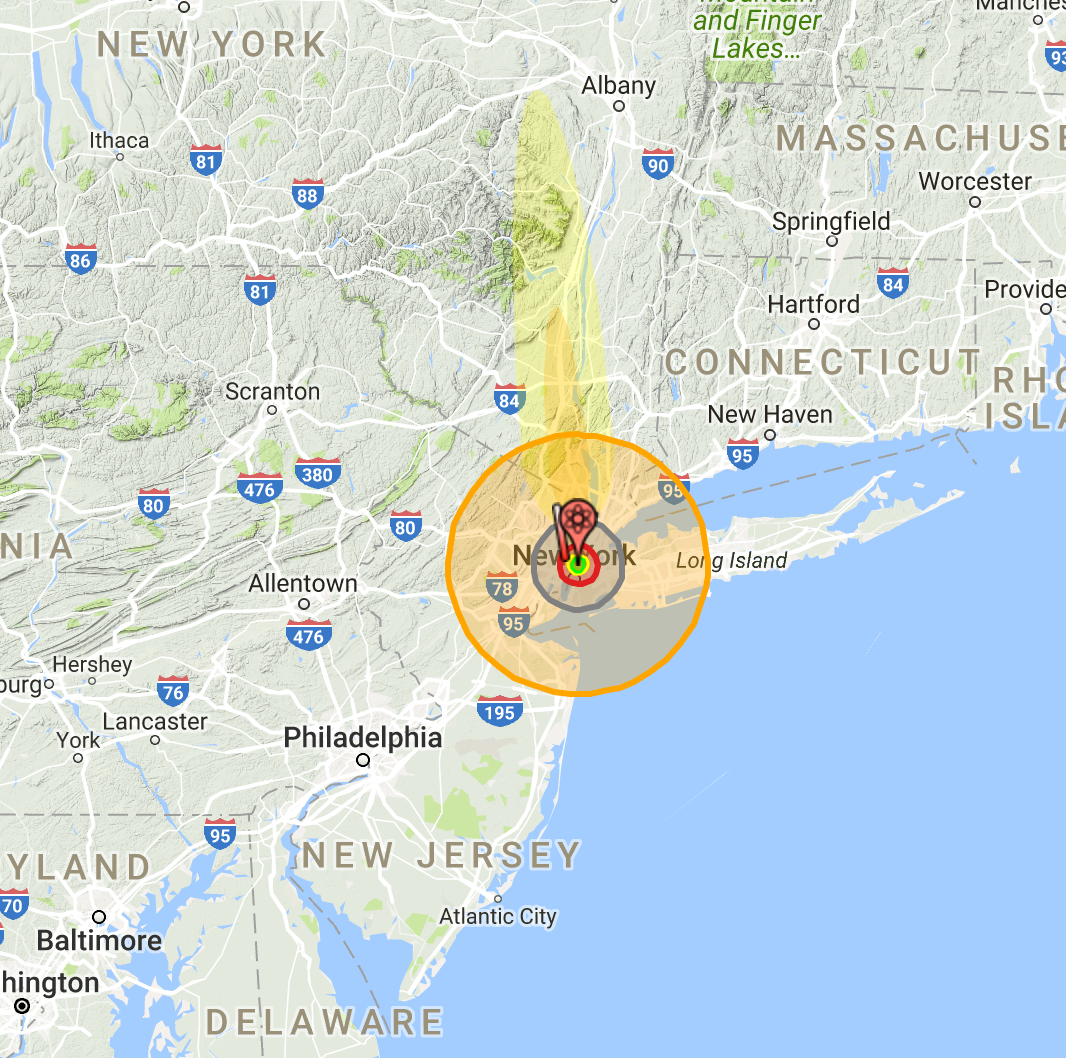

“Nukemap,” the creation of Alex Wellerstein, a historian of nuclear science and policy, is a simulator that allows you to conduct a mock nuclear strike. One can select nukes like the American bombs dropped on Japan in 1945 or Soviet weapons of the 1960s, as well as bombs modeled on those recently tested by North Korea. You choose whether you want to detonate the bomb in the air or at the ground’s surface. You set the wind direction. Then you click “detonate” and watch multicolored circles appear on the map indicating things like the fireball radius, air blast radius and thermal radiation radius. The simulator calculates how many people just died. It is a power rush, one safely removed from reality. It is vivid but detached. And it may be just the contribution to our public policy debate that we need to really imagine a nuclear war.

“Nukemap” is a simulator that allows you to conduct a mock nuclear strike.

I first stumbled upon this simulator in the fall of 2013, when Bashar al-Assad crossed President Obama’s chemical weapons “red line.” The crisis was resolved by a Russian-brokered deal in which President Assad agreed to hand over his chemical weapons stockpile, and Mr. Obama was thus spared having to go to war. (In 2017 Assad used chemical weapons again.) I simulated a war between the superpowers then; now, I was curious to simulate a North Korean attack.

I detonated the nuke in Columbus Circle, a block away from America’s offices in Manhattan. I choose the yield to be the same as the North Korean nuclear device successfully tested in 2013, 15 kilotons. (Each “ton” refers to the explosive power of a metric ton of TNT; a kiloton is a thousand times that. A megaton is a million times that.) I set the wind direction based on the date of writing (Aug. 11). The simulator showed which areas of Manhattan would be flattened and predicted 145,350 initial casualties. Lethal fallout was shown spreading into the Hudson Valley.

Obviously, a bomb going off so close to where I work and live means I would not survive. But I was surprised at how much of the rest of Manhattan did survive. Next, I set off a 50-megaton Soviet 1961 RDS-220, or “Tsar Bomba,” the largest nuclear device ever detonated. All of New York City was engulfed, and an estimated 7,646,470 people were killed. Fallout reached deep into upstate New York. Again, I was clearly dead, but in both cases a nation survived the destruction of one of its biggest cities and even one of its biggest metropolitan regions. We are country that can take a punch, even a nuclear one.

I continued to set off nuclear bombs in New York and in other parts of the country. One notices with the simulator that the yield of the bomb matters tremendously; the altitude at detonation and the wind direction also which have a decisive impact on where and how far fallout spreads. From the way many Americans are discussing the current crisis, you could be forgiven for thinking the end of the world is near, but the simulations tell me otherwise. Even with its new capabilities, North Korea cannot threaten the survival of the United States. The largest bomb ever tested by the North Koreans had a maximum yield of 20 to 30 kilotons. That is not enough to take out even all Manhattan. In addition, our North Korean attackers would have to pick, at maximum, a couple of targets. We face not extinction but the loss of one or two of our cities.

This seems like little comfort, especially for those who live in a city. A strike would still mean hundreds of thousands of Americans dead. But it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the threat as well. I noticed that when I nuked San Francisco, the nearest big city to where my family lives, my small hometown of Davis escaped unscathed. Simulating a strike on Los Angeles, where many of my friends live, I noticed that much of the city would survive due to its sprawl. Nothing survives a direct hit, but I am comforted to know Los Angeles has been preparing to rescue survivors. Most serious foreign policy thinkers consider a North Korean attack unlikely. But it is a relief to know there are things we can do.

President Trump promised “fire and fury like the world has never seen” in retaliation for an attack against the United States. With that in mind I simulated the detonation of a 15-megaton bomb code-named “Castle Bravo”—the largest U.S. nuclear device ever tested. The simulator shows 2,421,600 people dying and fallout blanketing North Korea. With different wind patterns, the fallout could spread into South Korea, Russia or China. It is shocking to see just how devastating just one of our bombs can be.

Simulating nuclear strikes has answered some of my questions but also raised new ones. How accurate are the North Korean missiles? What are the moral questions surrounding retaliatory nuclear strikes? How will we know if a strike is launched? If the worst happens we will be facing unprecedented grief as well as profound moral questions. But it is useful for me to try and imagine that world and the realities of what we are facing. A democracy should not sleepwalk into a nuclear war, with citizens merely along for the ride. As citizens, informed debate is our duty.

![A home fallout shelter near Akron, Mich., captured by an unknown photographer in 1960. (National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency/(397-MA-2s-160)/[VENDOR # 125]) A home fallout shelter near Akron, Mich., captured by an unknown photographer in 1960. (National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency/(397-MA-2s-160)/[VENDOR # 125])](/sites/default/files/styles/related_story_img/public/main_image/postwar_080_v125.jpg?itok=r-j8BmwH)