How we got the Mass translation we have

That congregations and presiders both overwhelmingly dislike the 2010 English translation of the Roman Missal comes as no surprise, but the story behind its creation and the suppression of an earlier English translation—one that had been long in the works—is as intriguing as any mystery novel or detective film. In Lost in Translation:The English Language and the Catholic Mass, renowned systematic theologian Gerald O’Collins, S.J., and John Wilkins, former editor of the British weekly The Tablet, give us an accessible, exciting, informative and virtually unassailable account (historically, theologically and linguistically) of how we have come to receive this liturgical translation that has given us “the dewfall,” “for many,” “under my roof” and “with your spirit,” among other challenging expressions, each time we gather to celebrate the Eucharist.

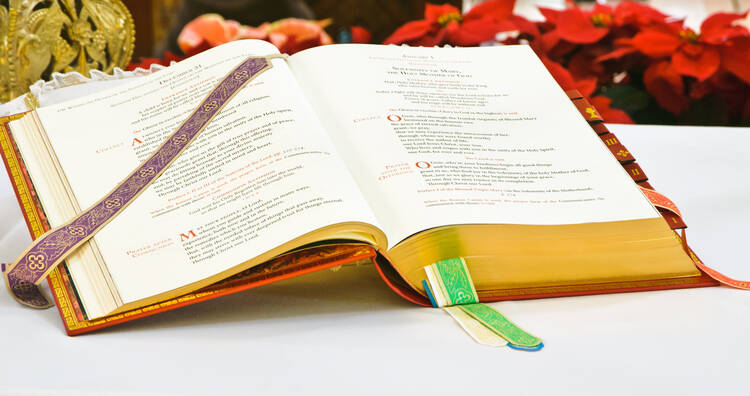

This short but impressively researched book opens with Wilkins’s page-turning account of how we got from Vatican II’s "Sacrosanctum Concilium" and the call for translations that facilitate “full active participation of all God’s holy people” (SC 41) to the 2010 English translation.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s curial officials—especially from the Congregation for Divine Worship (CDW)—stymied the ongoing and decades-long work of ICEL.

We learn of the establishment of ICEL (International Commission on English in the Liturgy) in 1963 by 11 bishops’ conferences from the English-speaking world, and how in the late 1990s and early 2000s curial officials—especially from the Congregation for Divine Worship (CDW)—stymied the ongoing and decades-long work of ICEL, issued idiosyncratic translation directives in the document "Liturgiam Authenticam" (2001) and established a new oversight committee named Vox Clara to ensure that the liturgical translation would reflect what the CDW wanted. Among their priorities was ostensibly a more literal translation from the Latin editio typica as opposed to what is often called “dynamic equivalent” translation, as well as the preference for so-called “sacral style” as opposed to conventional spoken English (the latter the CDW would deem language too quotidian for the liturgy).

As O’Collins painstakingly notes throughout the book, major contradictions exist between what the CDW and Vox Clara claim to have accomplished as set out in the directives of "Liturgiam Authenticam" and the translation as it actually exists. For example, there are numerous instances where not only does the 2010 English translation not reflect the literal meaning of the Latin, but also words are changed, added or their meaning adapted to fit what appears to be an ideological or aesthetic agenda rather than remain slavishly true to the editio typica. More egregious still is the introduction of theologically dubious, if not outright heretical, language into the liturgy (e.g., the preponderance of “merit” discourses found in the prayers of the liturgy that implies a not-so-subtle Pelagianism).

It isn’t too late to reclaim liturgical language that is more prayerful, understandable and theologically sound.

So what are we to do in the wake of this admittedly poor English translation of the Missal now seven years on? O’Collins and Wilkins suggest dusting off the 1998 ICEL revised translation that the CDW never allowed to see the light of day. The product of decades of work, accomplished by the best researchers, liturgists, theologians and translators, there already exists an English translation “waiting in the wings.” Given Pope Francis’s recent motu proprio (September 3, 2017), which restores to the local bishops’ conferences responsibility for translations, it isn’t too late to reclaim liturgical language that is more prayerful, understandable and theologically sound. But this will require humility and courage on the part of the episcopal conferences, which will have to concede first that the 2010 translation was misguided.