Late in the evening on Tuesday, Nov. 16, 1965, only 22 days before the closing of the Second Vatican Council, about 40 bishops gathered at the ancient Catacombs of St. Domitilla in Rome to celebrate the Eucharist. Early Christians living in the Eternal City held this long stretch of galleries and tombs in high regard. The bodies of many martyrs laid to rest there reminded them of living the Gospel in radical ways.

Most of those bishops were Latin American. There were also some from Europe, Africa, Asia and one from North America (a Canadian). Dom Hélder Câmara, then the bishop of Recife in Brazil, led the group. They signed an agreement known as the “Pact of the Catacombs.” Inspired by the spirit of the council, the bishops affirmed their faith in Jesus Christ and renewed their love for the Gospel.

The bishops committed to living in simple ways, without privileges, embracing austerity and poverty as well as the poor and the promotion of justice and liberation. They promised to advocate “laws, social structures and institutions that are necessary for justice, equality and the integral, harmonious development of the whole person and of all persons, and thus for the advent of a new social order, worthy of the children of God.”

Among the signatories of the pact were Bishops Manuel Larraín of Chile and Marcos Gregorio McGrath of Panama. Bishop McGrath was actively involved in the discussions that led to the “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World.” Bishop Larraín was the president of the newly created Latin American Episcopal Conference (better known as CELAM from its Spanish-language name, Consejo Episcopal Latinoamericano).

"Medellín would be the first and perhaps one of the most successful exercises of appropriation of the Second Vatican Council at the continental level."

A few weeks later, the bishops returned to their home dioceses inspired by the council and its final documents. It was time to bring Vatican II to life at the local level. Bishop Larraín and other bishops set in motion a series of events and planning processes that led to the Second General Conference of Latin American Bishops in Medellín, Colombia, in 1968. The new momentum of the council and the spirit of the pact signed that evening at the catacombs guided a new dawn for Latin American Catholicism. Medellín would be the first and perhaps one of the most successful exercises of appropriation of the Second Vatican Council at the continental level.

Latin America Appropriates the Vatican II

Latin America in the 1960s was fertile soil for the seeds of the council. More than 90 percent of the population self-identified as Catholic. While Europe, which had been traditionally associated with Catholicism, wrestled with increasing secularism, Latin America became the continent of Catholic hope.

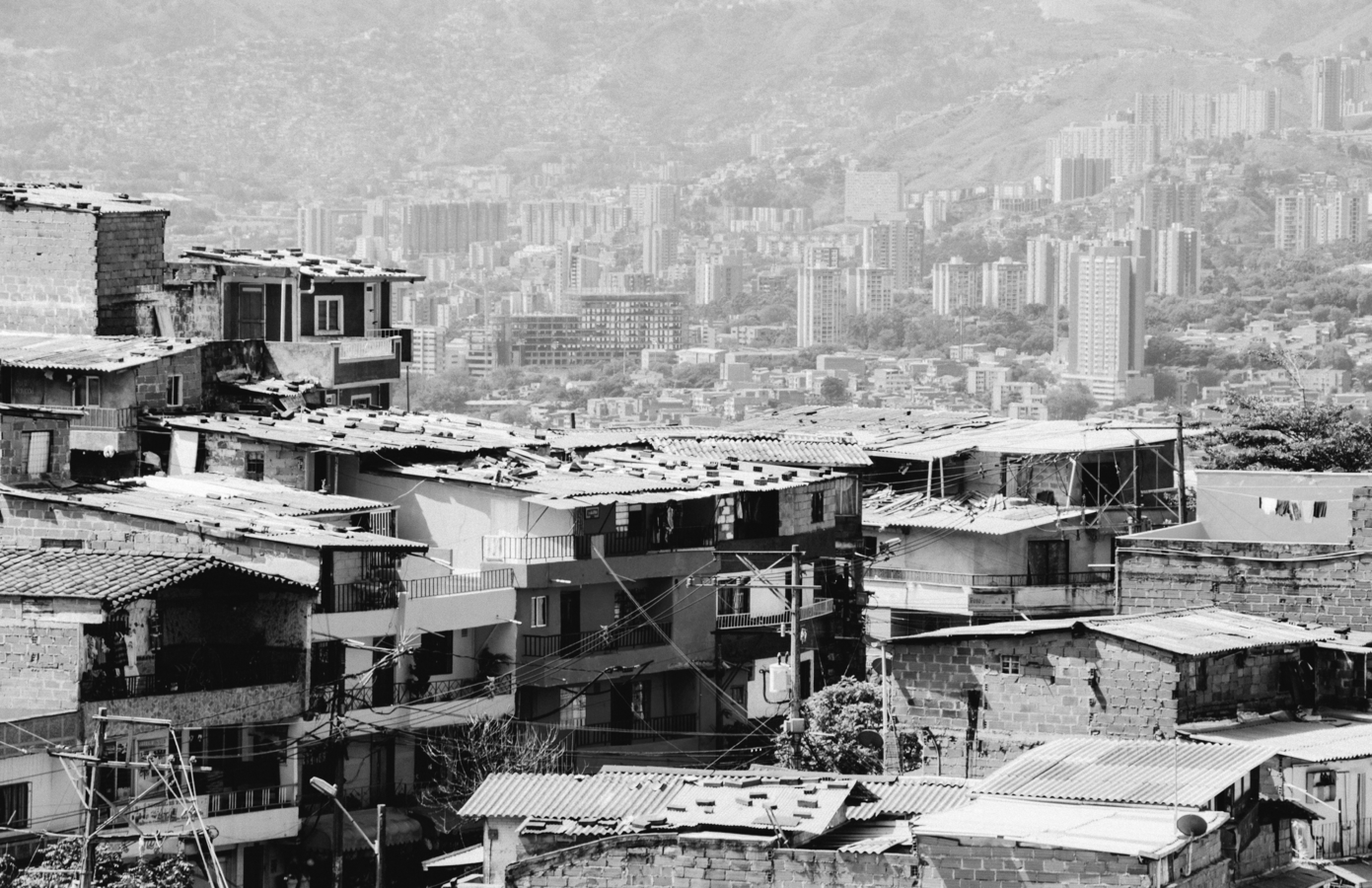

To be clear, it was a mixed hope. Poverty, inequality, corruption, political instability and illiteracy, among other social ills, were rampant. But countless Catholics throughout the continent were rereading the Scriptures in small communities and changing the ways and structures in which they lived as baptized Christians. Yes, there was hope.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the winds of economic, political and social transformation roared strongly throughout Latin America. Governments in the region had embraced so-called theories of development fueled by neocapitalist ideology, which focused mainly on economic growth. Policies and practices emerging from these theories benefitted only certain elites. The vast majority of Latin Americans lived in dehumanizing poverty.

Revolutions, internal wars, dictatorships and even the exploration of alternative ideologies like communism were common. But the lives of most people, especially the poor and those living in rural areas, changed little. Rather than acting as agents of their own destinies, Latin Americans were subject to forces upon which they had little or no control. There was a need for a different analysis of the reality and for fresher language that would affirm the dignity of every human person and provide a renewed sense of hope for all. Catholic pastoral leaders on the continent read the conclusions of the council with enthusiasm and seized the moment.

"Policies and practices emerging from these theories benefitted only certain elites. The vast majority of Latin Americans lived in dehumanizing poverty."

In 1965, Bishop Larraín wrote a pastoral letter entitled “Development: Success or Failure in Latin America.” He spoke of underdevelopment as an evil. To promote every person, he called for a humanism that would confront a threefold hunger: physical, cultural and spiritual. Bishop Larraín spoke of the existence of “vicious circles of misery that are the result of current structures.”

This insight brought to light the reality of structural sin. Latin American bishops and theologians began to talk about the need to address the root causes of structural violence, poverty and oppression. The Gospel demanded new ways of being and acting that affirmed the dignity of every human person. Pope Paul VI echoed several of these insights in his 1967 encyclical “Populorum Progressio,” writing that the “development we speak of here cannot be restricted to economic growth alone. To be authentic, it must be well rounded.”

An authentically Latin American model of theological and pastoral reflection was emerging through meetings across the continent. The work of theologians like Gustavo Gutiérrez, O.P. (who was a diocesan priest at the time), Juan Luis Segundo, S.J., and the Rev. Lucio Gera was highly influential. In his writings, Father Gutiérrez referred to a theology committed to denouncing the causes of underdevelopment and its sinfulness. Because Christianity is holistically liberating, the liberation that Jesus Christ brings to humanity also involves liberation from oppressive realities in history. Between 1965 and 1968, Latin American bishops met in Chile, Ecuador, Colombia, Peru and Brazil and developed the framework, language and focus that would characterize Medellín.

The Way of Medellín

Medellín revolutionized pastoral and theological reflection in Latin America. The conversations leading to it, the meeting itself and its conclusions set the tone, language and method for how Latin American Catholics and many other Catholics throughout the world would reflect on evangelization during the next half century.

In his 1975 apostolic exhortation “On Evangelization in the Modern World,” Pope Paul VI echoed the language of liberation used in Medellín: “Between evangelization and human advancement—development and liberation―there are in fact profound links.” More recently, the Fifth General Conference of Latin American Bishops in Aparecida, Brazil, in 2007 and Pope Francis’ five-year-old pontificate have served as clear reminders that the wisdom and insights from Medellín are very much alive.

"Informed by this on-the-ground theological reflection, pastoral action should respond to the particular realities that shape the lives of God’s people here and now."

Medellín seamlessly integrated and further developed the well-known see-judge-act method, popularized by Cardinal Joseph Leo Cardijn of Belgium in the years preceding the council. The method is an invitation to engage reality with a critical eye, evaluate it from the perspective of the faith using the best available tools for discernment and act upon such reality in an informed manner seeking transformation. In Medellín, the method evolved into an instrument of social analysis. During the years of preparation, leaders met regularly with social scientists, anthropologists and other experts to understand Latin America. These conversations embraced a model of reflection based on the conviction that theology is to follow conversion and spring from a grounded understanding of people’s reality.

Theology emerges as a “second moment” or a “second act.” Informed by this on-the-ground theological reflection, pastoral action should respond to the particular realities that shape the lives of God’s people here and now.

Medellín also tested Vatican II’s vision of church as the “people of God” by placing it in the concrete realities of Latin America, where most people experienced poverty. That meant starting where the people lived and understanding who they were. If the church was to respond to the challenges of being Christian in Latin America, it could not do it without listening to the diversity of voices and experiences that constitute the people of God.

In Latin America in 1968, the church knew itself as a poor church because most of its members experienced poverty. The poor had to play a central role in the reflection about evangelization and the building of the church on the continent. This meant guaranteeing the creation of spaces where bishops, members of the clergy, theologians, elites and others could attentively listen to people’s voices and honor their wisdom.

Small communities provided a space for personal encounter, growth in the faith in a communal environment and the advancement of works to promote the human person, particularly the poor. For Medellín, the building of ecclesial communion starts from below, in the particular circumstances where people encounter Jesus Christ and his Gospel every day. When that does not happen, reform is needed.

"On a continent marred by poverty and its effects, Medellín acknowledged and affirmed the voice of the poor and their role in transforming the church and society in light of the Gospel."

Furthermore, Medellín speaks explicitly of the sociopolitical dimensions of evangelization. It names the essential relationship between the church’s mission and the engagement of the Christian community to bring about the common good. In their final message to the people of Latin America, the bishops gathered at Medellín invited Catholics to join them in their decision to “inspire, encourage and press for a new order of justice that incorporates all [people] in the decision-making of their own communities.”

In this sense, Medellín calls all the baptized to act as agents of change in society. On a continent marred by poverty and its effects, Medellín acknowledged and affirmed the voice of the poor and their role in transforming the church and society in light of the Gospel. Medellín called for the creation of conditions for all to flourish.

Evangelization is more than raw indoctrination or merely giving material assistance without helping recipients take ownership of their futures. Evangelization is about proclaiming the good news while promoting the human person and the common good in response to God’s will. Evangelization demands the conversion of structures, many of which embody sin, to further justice and solidarity. Evangelization, therefore, leads to a reform of ecclesial structures and mentalities—what today we call pastoral conversion—so the church can be an authentic sign of Christian liberation for all, as are Jesus and his Gospel.

Medellín reminded Catholics that evangelization “must direct itself toward the formation of a personal, internalized, mature faith.” A mature faith is a faith capable of reading the signs of the times, which “are expressed above all else in the social order.” These are “signs from God” to which we must respond inspired by the desire to promote social justice. At the risk of becoming irrelevant and disconnected, the church in its evangelizing efforts should not ignore reality with its demands and possibilities. Neither should it ignore poor people’s everyday experiences.

A Step Forward on the Reflection about Poverty

Early reception of Vatican II among U.S. Catholics stressed the insights of the “Decree on Ecumenism,” the “Declaration on the Relationship of the Church to Non-Christian Religions” and the “Declaration on Religious Freedom.” In Latin America, reception of the council focused on the “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World” (salvation in history) and the “Dogmatic Constitution on the Church” (the people of God among the peoples of the earth).

The bishops gathered at Medellín also further discussed topics treated in a limited way at the council: the church of the poor, a church committed to liberation and human promotion, a church that denounced poverty. In this way, the church in Latin America was doing theology in light of its own ecclesial and social reality. From that reality, which is a rich font of theological and pastoral insight, it continues to inform the rest of the Catholic world.

"Medellín was not shy about highlighting the disturbing correlation between small elites becoming richer and more powerful while the vast majorities drown in poverty and anonymity."

Medellín built upon the conviction that to follow Jesus is to journey with our sisters and brothers who are poor, the crucified ones of history. The bishops at Medellín spoke of social injustices that kept the majority of people in Latin America living in “dismal poverty, which in many cases becomes inhuman wretchedness.” Medellín did not limit itself to “talk about” poverty. Its novelty was in the courage to name and unmask the causes of poverty as part of the process of following Jesus.

Naming the evident relationship between inequality and poverty—and the sinfulness of the unjust conditions that lead to them—has gained Medellín plenty of enthusiasts as well as detractors. Medellín was not shy about highlighting the disturbing correlation between small elites becoming richer and more powerful while the vast majorities drown in poverty and anonymity. Today we know that 1 percent of the world’s population owns more than half of all existing wealth. More than two-thirds of the wealth produced in recent years has gone into the hands of that 1 percent.

But the bishops gathered at Medellín wanted more than a mere declaration. They met to identify commitments and actions for change. In their own words: “This assembly has been invited to take a decision and establish programs only under the condition that we are disposed to carry them out as a personal commitment even at the cost of sacrifice.” Medellín captured the voice of a portion of the church that has much to say to the rest of the world, with its own language, committed to the necessary transformations to live its mission.

Medellín in the United States

During the last 50 years, Medellín has been studied, discussed and appropriated in various contexts in the United States. Pope Paul VI’s encyclical letter “Populorum Progressio” provided U.S. Catholics with important language with which to understand Latin America and paved the way for robust conversations about Medellín. Theology and ministerial formation programs in Catholic universities and seminaries throughout the country have been instrumental in introducing students to Medellín.

Medellín is often associated with the methods and reflections of Latin American theologies of liberation. From this perspective, Medellín has been a natural conversation partner for U.S. Catholic black, Hispanic, Asian and feminist theologies, among others, insofar as it shares common language, concerns and methods with these bodies of theological thought. We should not, however, miss the particularity of Medellín. It was the collective voice and shared wisdom of the Latin American Catholic bishops in 1968, a voice and wisdom echoed loudly for five decades, despite critiques and even opposition in some sectors in the Catholic world.

"Hispanic Catholics, soon to constitute half of all Catholics in the United States, have channeled the wisdom of Medellín into the life of the church in this country."

Hispanic Catholics, who will soon constitute half of all Catholics in the United States, have channeled the wisdom of Medellín into the life of the church in this country. Millions of Catholic immigrants from Latin America were evangelized in its spirit and bring that formation to enrich the life of the church in the United States. The Mexican American Cultural Center in San Antonio, Tex., now a college, for decades facilitated conversations among scholars and pastoral leaders from Latin America and the United States on topics associated with Medellín. Several Hispanic Catholic theologians have intentionally incorporated the insights of Medellín into their work.

The pastoral theologian Edgard Beltran worked for CELAM in the planning of Medellín and participated actively in the meeting. In the 1970s, he started working with Hispanic pastoral leaders in the United States, a partnership that soon led to the development of processes of consultation and evangelization grounded in the vision of Vatican II and Medellín. These Encuentros, or encounters, used the see-judge-act method. The Encuentros—convened nationally in 1972, 1977, 1985, 2000 and 2018—have served as catalysts to assess the church’s institutional response to the fast-growing Hispanic presence. They affirm the influence of Hispanic Catholics in the building of the church in this corner of the world as well as the transformation of the larger U.S. society.

From Latin America to the World

The bishops who signed the “Pact of the Catacombs” in Rome most likely did not know where that commitment would take them. Yet they trusted the Holy Spirit in the same way St. John XXIII did as he convoked the Second Vatican Council that brought them together. For those who returned to Latin America, the spirit of the pact found life in Medellín.

Fifty years later, Medellín continues to inspire the church in Latin America and the rest of the world. Tens of thousands of Catholics committed to living the Gospel by serving the poor and promoting justice and liberation have lost their lives in Latin America, including leaders like Bishop Enrique Angelelli from Argentina, one of the signatories of the pact, and Archbishop Óscar Romero from El Salvador. Their blood is the seed of new Christians.

"When Pope Francis speaks about a poor church for the poor, he echoes the best of Catholic social teaching and Latin American theology, sharing the heart of Jesus’ message."

Many Catholics on the continent continue to work tirelessly to live out their missionary discipleship by serving the poor and those who are most vulnerable, promoting the whole person and changing those structures of sin that prevent far too many people from flourishing. Their witness demonstrates the need for Medellín.

When Pope Francis speaks about a poor church for the poor, he echoes the best of Catholic social teaching and Latin American theology, sharing the heart of Jesus’ message. Fifty years ago, Medellín did likewise. A poor church, the bishops wrote at Medellín, “denounces the unjust lack of this world’s goods and the sin that it begets; preaches and lives in spiritual poverty, as an attitude of spiritual childhood and openness to the Lord; is herself bound to material poverty.” Medellín promoted participation, consultation and formation. The meeting itself was a fruitful exercise of synodality, and represents a church that went from being “a mirror church” to a “source church”. Pope Francis has emerged on the global stage as a church leader who affirms the importance of synodality and regularly proceeds in a synodal way.

In his passion for the truth of the Gospel, his invitation to be a poor church and to love the poor with preferential love, his respect for social movements and his respect for synodality, Pope Francis brings the best of Medellín as a gift to the world. Fifty years later, the message and wisdom of Medellín resonate vigorously with the experience of most Catholics in all continents.

You're making my eyes bleed. Until the Catholic Church worldwide recognizes that property rights and attendant social institutions which enshrine honesty are required conditions for economic progress, they will condemn hundreds of millions to poverty. It's that simple.

In the wrong direction both spiritually and politically. They miss the one thing that makes a difference in the human spirit, freedom. And for that they are steering the Church against the tide of progress. The poor are disappearing from the world and the Church's policies will inhibit this process. They use the word "reality" a dozen times but then ignore reality at every turn and never mention freedom. How could they be so blind?

The authors should ask how the most Catholic area of the world became one of the poorest and most violent? They use the words "poor/poverty" 38 times but don't ask why some very large areas of the world are not poor. That is the reality they ignore. The answers are available, maybe they should. look at them.

Aside: two of America, the magazine, authors are darlings of socialism, Elizabeth Bruenig and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. When will we see them again?

I have read here a lot of brave declarations and theological buzzwords, but have to ask what the real-world results have been. Latin America continues to export its impoverished people to the United States, to engage in horrendous violence within its communities, to produce children that it cannot feed, and to some extent to desert the RC Church. And let us not pretend that this influx of the impoverished is somehow a blessing to the United States.

Scanning this I couldn't help thinking about all the bishops in Chile who resigned after yet another big sex abuse scandal surfaced within the Catholic church. It does seem that the bishops and cardinals and even the pope should step down from their lofty and uncaring positions. The pope clearly cares but he is old and and overwhelmed and seems unsure how to proceed from here.

The church needs to be for the poor, as Jesus was. It doesn't need layers of bureaucratic structure between Christ's clear call to pool our resources and help the needy even if we have to sell our homes to do so. That's the spirit that has been long gone from the church. And efforts to recapture this spirit in Latin America may not be perfect but they are in the right direction; they are efforts to carry out Jesus' message.

Scanning this I couldn't help thinking about all the bishops in Chile who resigned after yet another big sex abuse scandal surfaced within the Catholic church. It does seem that the bishops and cardinals and even the pope should step down from their lofty and uncaring positions. The pope clearly cares but he is old and and overwhelmed and seems unsure how to proceed from here.

The church needs to be for the poor, as Jesus was. It doesn't need layers of bureaucratic structure between Christ's clear call to pool our resources and help the needy even if we have to sell our homes to do so. That's the spirit that has been long gone from the church. And efforts to recapture this spirit in Latin America may not be perfect but they are in the right direction; they are efforts to carry out Jesus' message.

Perhaps an editor can delete my earlier comment. I was trying to edit that comment by breaking it into two paragraphs, and instead I produced two identical comments except for the number of paragraphs. And now I have produced a third comment. More than enough from me.

Perhaps an editor can delete my earlier comment. I was trying to edit that comment by breaking it into two paragraphs, and instead I produced two identical comments except for the number of paragraphs. And now I have produced a third comment. More than enough from me.

Perhaps an editor can delete my earlier comment. I was trying to edit that comment by breaking it into two paragraphs, and instead I produced two identical comments except for the number of paragraphs. And now I have produced a third comment. More than enough from me.

Yikes. Sorry. I'm outa here. I'm too old for this mode of communication.

It’s easy. After each comment there is an edit button. Just push/click it and erase everything and say duplicate. Eventually someone will erase the comment with duplicate in it. You can also put another comment in it. For example, split your original message into separate paragraphs.