Like paper, print, steel and the wheel, computer-generated artificial intelligence is a revolutionary technology that can bend how we work, play and love. It is already doing so in ways we can and cannot perceive.

As Facebook, Apple and Google pour billions into A.I. development, there is a fledgling branch of academic ethical study—influenced by Catholic social teaching and encompassing thinkers like the Jesuit scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin—that aims to study its moral consequences, contain the harm it might do and push tech firms to integrate social goods like privacy and fairness into their business plans.

“There are a lot of people suddenly interested in A.I. ethics because they realize they’re playing with fire,” says Brian Green, an A.I. ethicist at Santa Clara University. “And this is the biggest thing since fire.”

“There are a lot of people suddenly interested in A.I. ethics because they realize they’re playing with fire. And this is the biggest thing since fire.”

The field of A.I. ethics includes two broad categories. One is the philosophical and sometimes theological questioning about how artificial intelligence changes our destiny and role as humans in the universe; the other is a set of nuts-and-bolts questions about the impact of powerful A.I. consumer products, like smartphones, drones and social media algorithms.

The first is concerned with what is termed artificial general intelligence. A.G.I. describes the kind of powerful artificial intelligence that not only simulates human reasoning but surpasses it by combining computational might with human qualities like learning from mistakes, self-doubt and curiosity about mysteries within and without.

A popular word—singularity—has been coined to describe the moment when machines become smarter, and maybe more powerful, than humans. That moment, which would represent a clear break from traditional religious narratives about creation, has philosophical and theological implications that can make your head spin.

But before going all the way there—because it is not all that clear that this is ever going to happen—let us talk about the branch of A.I. ethics more concerned with practical problems, like if it is O.K. that your phone knows when to sell you a pizza.

“For now, the singularity is science fiction,” Shannon Vallor, a philosophy professor who also teaches at Santa Clara, tells me. “There are enough ethical concerns in the short term.”

The ‘Black Mirror’ factor

While we ponder A.G.I., artificial narrow intelligence is already here: Google Maps suggesting the road less traveled, voice-activated programs like Siri answering trivia questions, Cambridge Analytica crunching private data to help swing an election, and military drones choosing how to kill people on the ground. A.N.I. is what animates the androids in the HBO series “Westworld”—that is, until they develop A.G.I. and start making decisions on their own and posing human questions about existence, love and death.

Even without the singular, and unlikely, appearance of robot overlords, the possible outcomes of artificial narrow intelligence gone awry include plenty of apocalyptic scenarios, akin to the plots of the TV series “Black Mirror.” A temperature control system, for example, could kill all humans because that would be a rational way to cool down the planet, or a network of energy-efficient computers could take over nuclear plants so it will have enough power to operate on its own.

The more programmers push their machines to make smart decisions that surprise and delight us, the more they risk triggering something unexpected and awful.

The invention of the internet took most philosophers by surprise. This time, A.I. ethicists view it as their job to keep up.

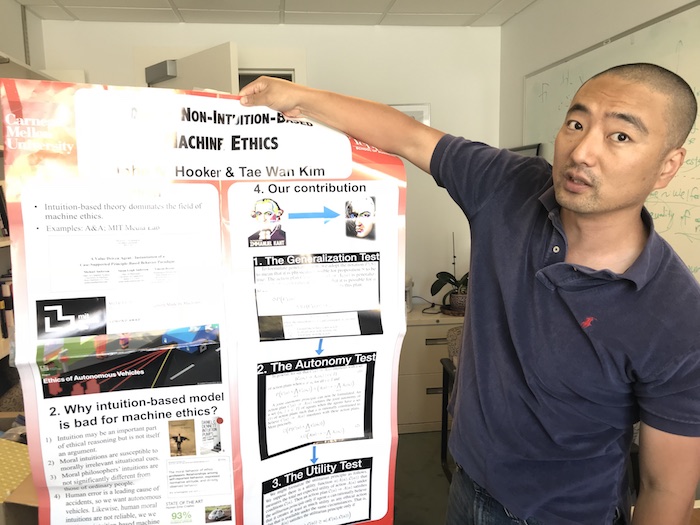

“There’s a lack of awareness in Silicon Valley of moral questions, and churches and government don’t know enough about the technology to contribute much for now,” says Tae Wan Kim, an A.I. ethicist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. “We’re trying to bridge that gap.”

A.I. ethicists consult with schools, businesses and governments. They train tech entrepreneurs to think about questions like the following. Should tech companies that collect and analyze DNA data be allowed to sell that data to pharmaceutical firms in order to save lives? Is it possible to write code that offers guidance on whether to approve life insurance or loan applications in an ethical way? Should the government ban realistic sex robots that could tempt vulnerable people into thinking they are in the equivalent of a human relationship? How much should we invest in technology that throws millions of people out of work?

Tech companies themselves are steering more resources into ethics, and tech leaders are thinking seriously about the impact of their inventions. A recent survey of Silicon Valley parents found that many had prohibited their own children from using smartphones.

The more programmers push their machines to get creative and make smart decisions, the more they risk triggering something unexpected and awful.

Mr. Kim frames his work as that of a public intellectual, reacting to the latest efforts by corporations to show they are taking A.I. ethics seriously.

In June, for example, Google, seeking to reassure the public and regulators, published a list of seven principles for guiding its A.I. applications. It said that A.I. should be socially beneficial, avoid creating or reinforcing unfair bias, be built and tested for safety, be accountable to people, incorporate privacy design principles, uphold high standards of scientific excellence, and be made available to uses that accord with these principles.

In response, Mr. Kim published a critical commentary on his blog. The problem with promising social benefits, for example, is that “Google can take advantage of local norms,” he wrote. “If China allows, legally, Google to use AI in a way that violates human rights, Google will go for it.” (At press time, Google had not responded to multiple requests for comment on this criticism.)

The biggest headache for A.I. ethicists is that a global internet makes it harder to enforce any universal principle like freedom of speech. The corporations are, for the most part, in charge. That is especially true when it comes to deciding how much work we should let machines do.

The invention of the internet took most philosophers by surprise. This time, A.I. ethicists view it as their job to keep up.

An argument familiar to anybody who has ever studied economics is that new technologies create as many jobs as they destroy. Thus the invention of the cotton gin in the 19th century called for industries dedicated to producing the necessary parts of wood and iron. When horses were replaced as a primary form of transportation, stable hands found jobs as auto mechanics. And so on.

A.I. ethicists say the current technological revolution is different because it is the first to replicate intellectual tasks. This kind of automation could create a permanently underemployed class of people, says Mr. Kim.

A purely economic response to unemployment might be a universal basic income, or distribution of cash to every citizen, but Mr. Kim says A.I. ethicists cannot help returning to the realization that lives without purposeful activity, like a job, are usually miserable. “Catholic social teaching is an important influence for A.I. ethicists, because it addresses how important work is to human dignity and happiness,” he explains.

“Money alone doesn’t give your life happiness and meaning,” he says. “You get so many other things out of work, like community, character development, intellectual stimulation and dignity.” When his dad retired from his job running a noodle factory in South Korea, “he got money, but he lost community and self-respect,” says Mr. Kim.

That is a strong argument for valuing a job well done by human hands; but as long as we stick with capitalism, the capacity of robots to work fast and cheap is going to make them attractive, say A.I. ethicists.

“Maybe religious leaders need to work on redefining what work is,” says Mr. Kim. “Some people have proposed virtual reality work,” he says, referring to simulated jobs within computer games. “That doesn’t sound satisfying, but maybe work is not just gainful employment.”

There is also a chance that the impact of automation might not be as bad as feared. A company in Pittsburgh called Legal Sifter offers a service that uses an algorithm to read contracts and detect loopholes, mistakes and omissions. This technology is possible because legal language is more formulaic than most writing. “We’ve increased our productivity seven- or eightfold without having to hire any new people,” says Kevin Miller, the company’s chief executive. “We’re making legal services more affordable to more people.”

But he says lawyers will not disappear: “As long as you have human juries, you’re going to have human lawyers and judges…. The future isn’t lawyer versus robot, it’s lawyer plus robot versus lawyer plus robot.”

Autonomous cars and the Trolley Problem

The most common jobs for American men are behind the wheel. Now self-driving vehicles threaten to throw millions of taxi and truck drivers out of work.

We are still at least a decade away from the day when self-driving cars occupy major stretches of our highways, but the automobile is so important in modern life that any change in how it works would greatly transform society.

Autonomous automobiles raise dozens of issues for A.I. ethicists. The most famous is a variant of the so-called trolley problem, a concept popularized by philosopher Philippa Foot in the 1960s. A current version describes the dilemma a machine might face if a crowded bus is in its fast-moving path. Should it change direction and try to kill fewer people? What if changing direction threatens a child? The baby-or-bus bind one of those instantaneous, tricky and messy decisions that humans accept as part of life, even if we know we do not always make them perfectly. It is the kind of choice for which we know there might never be an algorithm, especially if one starts trying to calculate the relative worth of injuries. Imagine, for example, telling a bicyclist that taking his or her life is worth it to keep a busful of people out of wheelchairs.

Technology experts say that the trolley problem is still theoretical because machines presently have a hard time making distinctions between people and things like plastic bags and shopping carts, leading to unpredictable scenarios. This is largely because neuroscientists still have an incomplete grasp of how vision works.

Is it morally correct to tell an autonomous car to drive the speed limit when everybody else is driving 20 miles an hour over?”

“But there are many ethical or moral situations that are likely to happen, and they’re the ones that matter,” says Mike Ramsey, an automotive analyst for Gartner Research.

The biggest problem “is programming a robot to break the law on purpose,” he says. “Is it morally correct to tell the computer to drive the speed limit when everybody else is driving 20 miles an hour over?”

Humans break rules in reasonable ways all the time. For example, letting somebody out of a car outside of a crosswalk is almost always safe, if not always technically legal. Making that distinction is still almost impossible for a machine.

And as programmers try to make this type of reasoning possible for machines, invariably they base their algorithms on data derived from human behavior. In a fallen world, that’s a problem.

“There’s a risk of A.I. systems being used in ways that amplify unjust social biases,” says Ms. Vallor, the philosopher at Santa Clara University. “If there’s a pattern, A.I. will amplify that pattern.”

Loan, mortgage or insurance applications could be denied at higher rates for marginalized social groups if, for example, the algorithm looks at whether there is a history of homeownership in the family. A.I. ethicists do not necessarily advocate programming to carry out affirmative action, but they say the risk is that A.I. systems will not correct for previous patterns of discrimination.

Ethicists are also concerned that relying on A.I. to make life-altering decisions cedes even more influence than they already have to corporations that collect, buy and sell private data, as well as to governments that regulate how the data can be used. In one dystopian scenario, a government could deny health care or other public benefits to people deemed to engage in “bad” behavior, based on the data recorded by social media companies and gadgets like Fitbit.

Every artificial intelligence program is based on how a particular human views the world, says Mr. Green, the ethicist at Santa Clara. “You can imitate so many aspects of humanity,” he says, “but what quality of people are you going to copy?”

“Copying people” is the aim of a separate branch of A.I. that simulates human connection. A.I. robots and pets can offer the simulation of friendship, family, therapy and even romance.

Already, some people say they are in “relationships” with robots, creating strange new ethical questions.

One study found that autistic children trying to learn language and basic social interaction responded more favorably to an A.I. robot than to an actual person. But the philosopher Alexis Elder argues that this constitutes a moral hazard. “The hazard involves these robots’ potential to present the appearance of friendship to a population” who cannot tell the difference between real and fake friends, she writes in the essay collection Robot Ethics 2.0: From Autonomous Cars to Artificial Intelligence. “Aristotle cautioned that deceiving others with false appearances is of the same kind as counterfeiting currency.”

Another form of counterfeit relationship A.I. technology proposes is, not surprisingly, romance. Makers of new lines of artificial intelligence dolls costing over $10,000 each claim, as one ad says, to “deliver the most enjoyable conversation and interaction you can have with a machine.”

Already, some people say they are in “relationships” with robots, creating strange new ethical questions. If somebody destroys your robot, is that murder? Should the government make laws protecting your right to take a robot partner to a ballgame or on an airplane trip, or to take bereavement leave if it breaks?

Even Dan Savage, the most famous sex columnist in the United States, sounds a cautionary note. “Sex robots are coming whether we like it or not,” he tells me. “But we will have to take a look at the real impact they’re having on people’s lives.”

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s wild ride

Inevitably, ethicists tackling A.N.I. run into the deeper philosophical questions posed by those who study A.G.I. One example of how narrow intelligence can appear to turn into a more general form came when a computer program beat Lee Sedol, a human champion of the strategic game Go, in 2016. Early in the game, the machine, Alpha Go, played a move that did not make sense to its human onlookers until the very end. That mysterious creativity is an intensely human quality, and a harbinger of what A.G.I. might look like.

A.G.I. theorists pose their own set of questions. They debate whether tech firms and governments should develop A.G.I. as quickly as possible to work out all the kinks, or block its development in order to forestall machines’ taking over the planet. They wonder what it would be like to implant a chip in our brain that would make us 200 times smarter, or immortal or turn us into God. Might that be a human right? Some even speculate that A.G.I. is itself a new god to be worshipped.

But the singularity, if it happens, poses a definite problem for thinkers of almost every religious bent, because it would be such a clear break from traditional narratives.

“Christians are facing a real crisis, because our theology is based on how God made us autonomous,” says Mr. Kim, who is a Presbyterian deacon. “But now you have machines that are autonomous, too, so what is it that makes us special as humans?”

One Catholic thinker who thought deeply about the impact of artificial intelligence is Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a French Jesuit and scientist who helped to found a school of thought called transhumanism, which views all technology as an extension of the human self.

“His writings anticipated the internet and what the computer could do for us,” says Ilia Delio, O.S.F., a professor at Villanova.

Teilhard de Chardin viewed technology with a wide lens. “The New Testament is a type of technology,” says Sister Delio, explaining the point of view. “Jesus was about becoming something new, a transhuman, not in the sense of betterment, but in the sense of more human.”

Critics of transhumanism say that it promotes materialistic and hedonistic points of view. In a recent essay in America, John Conley, S.J., of Loyola University Maryland, called the movement “a cause for alarm.” He wrote: “Is there any place for people with disabilities in this utopia? Why would we want to abolish aging and dying, essential constituents of the human drama, the fountainhead of our art and literature? Can there be love and creativity without anguish? Who will flourish and who will be eliminated in this construction of the posthuman? Does nature itself have no intrinsic worth?”

Teilhard’s writings have also been tainted by echoes of the racist eugenics popular in the 1920s. He contended, for example, that “not all ethnic groups have the same value.”

But his purely philosophical arguments about technology have regained currency among Catholic thinkers this century, and reading Teilhard can be a wild ride. Christian thinkers conventionally say, as St. John Paul II did, that every technological conception should advance the natural development of the human person. Teilhard went farther. He reasoned that technology, including artificial intelligence, could link all of humanity, bringing us to a point of ultimate spiritual unity through knowledge and love. He termed the moment of global spiritual coming-together the Omega Point. And it was not the kind of consumer conformism that tech executives dream about.

“Now you have machines that are autonomous, too, so what makes us special as humans?”

“This state is obtained not by identification (God becoming all) but by the differentiating and communicating action of love (God all in everyone). And that is essentially orthodox and Christian,” Teilhard wrote.

This idealism is similar to that of Tim Berners-Lee, one of the scientists who wrote the software that created the internet. The purpose of the web was to serve humanity, he said in a recent interview with Vanity Fair. But centralized and corporate control, he said, has “ended up producing—with no deliberate action of the people who designed the platform—a large-scale emergent phenomenon which is anti-human.” He and others now say the accumulation and selling of personal data dehumanizes and commodifies people, instead of enhancing their humanity.

Interestingly, the A.I. debate provokes theological questioning by people who usually do not talk all that much about God.

Juan Ortiz Freuler, a policy fellow at the Washington-based World Wide Web Foundation, which Mr. Berners-Lee started to protect human rights, says he hears people in the tech industry “argue that a system so complex we can’t understand it is like a god.” But it is not a god, says Mr. Freuler. “It’s a company wearing the mask of a god. And we don’t always know what their values are.”

You do not have to worship technology as a god to realize that our choices, and lives, are increasingly influenced by decision-making software. But as every A.I. ethicist I talked to told me, we should not be confused about who is responsible for making the important decisions.

“We still have our freedom,” says Sister Delio. “We can still make choices.”

A human Go player has played perhaps tens of thousands of games. I believe the Go-playing AI played millions of games with itself, losing and winning millions of games in preparation. The level of "experience" is higher. In the case of any rule based game, the number of possibilities is defined enough. The question is whether a similar process can be applied to real life situations. In this case, the AI would have to play millions of games in a simulation and its skill level would depend if the simulation is accurate and complex enough to mirror reality. Or so I understand it. I guess I should get a textbook on neural networks. What fascinates me is not so much that we can do the things we do but that we are aware of the doing. Very strange.

An article in the September, 2018 issue of the Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers publication “Computer” by Plamen P. Angelov and Xiaowei Gu of Lancaster University, entitled “Toward Anthropomorphic Machine Learning” sprinkles a little engineering reality on the capability of some of the more popular approaches to Artificial Intelligence that various commercial and governmental entities attempt to implement. The approach in question is called “Deep Learning Neural Networks” or DLNN. The authors supply end-note superscripts that refer to sources that the authors use to corroborate their case, but the notes are not reproduced here, for brevity.

“LIMITS AND CHALLENGES OF DEEP LEARNING

“The mainstream DLNNs, despite their success (reported results are comparable to or superior to human ability) and publicity (including the commercial version), as well as increasing media interest, still have a number of unanswered questions and deficiencies, as described below.

“The internal architecture of DLNNs is opaque … (there are many ad hoc decisions and parameters, such as number of layers, neurons, and parameter values).

“The training process of DLNNs requires a large amount of data, time, and computational resources, which preclude training and adaptation in real time; therefore, DLNNs cannot cope with the evolving nature of the data (they have a fixed structure and settings, for example, the number of classes), and they also cannot learn ‘from scratch.’

“DLNNs are prone to overfitting. DLNNs cannot handle uncertainty. Not only do they perform poorly on inference data that is significantly different from the training data, but they are also UNAWARE of this (meaning that it is practically impossible to analyze the reasons for errors and failures); they can be easily fooled and thus output high-confidence scores even when facing unrecognizable images.“

The whole article and, indeed the entire issue is worth reading. It should be noted that technologists often take ethical issues just as seriously as do ethicists.

On a slightly different issue related to the use of AI, it seems that we often forget the layers of protection provided by law and regulation on the safety and effectiveness of human and technology-assisted services that affect public safety. There is a reason for the state-federal licensing system for physicians, engineers who do public engineering projects, lawyers, teachers, various clinicians doing counseling-related work, aviation certifications, drug approvals, and many more professional and skilled trade services and providers. The licensing process involves documented years of pre-licensing experience, formal testing using approved protocols, and background checking. Applying similar standards to AI-generated services affecting public safety and welfare will demand that AI systems be fully susceptible to analysis to insure safety and effectiveness, which means that the processes must be understandable to legislative and regulatory staffs.

Global Digital Forum (GDF) is a global technology conference that has been uniquely designed to bring together an unparalleled line-up of business leaders, practitioners and customers from all over the world, engaged in driving change at the intersection of Artificial Intelligence, Security/Blockchain, Cloud Services and Internet-of-Things and key industry verticals.

Register here: http://promotions.plantautomation-technology.com/global-digital-forum-event