How has the Eucharist transformed your life?

People in the ancient world thought blessings had concrete effects. Such belief is not common today, when people treat blessings as symbolic activities. A blessing today might express concern after a sneeze, approval for a marriage or thanksgiving before a meal, but the words of the blessing manifest only an unseen, interior reality. Biblical people thought a blessing had a detectable effect on the material world. When Jacob “stole” Isaac’s blessing from his brother, for example, Isaac mourned that the blessing would now go to the wrong son. Although Isaac’s intent was to bless Esau, his eldest, once the words were uttered over Jacob, they transformed reality for both sons in a permanent way.

This gives context to the blessing that appears in this Sunday’s first reading. Melchizedek blesses Abram in a ritual that includes bread and wine. The implied effect of this blessing appears in the following chapter, when God offers a covenant to Abram (Gn 15:1-21). Though the two passages may have come from distinct traditions, the compilers of Genesis juxtaposed them to make it clear that the covenant God offered to Abram was, at least in part, the result of Melchizedek’s blessing.

‘Then taking the five loaves and the two fish, he said the blessing over them and gave them to the disciples to set before the crowd.’(Lk 9:16)

How have the words of Christ in the Eucharist

transformed your life?

How can your own words of blessing transform the life of another?

About Melchizedek Scripture preserves only this narrative in Gn 14:18-20. He was a priest of God but lived long before Aaron, and his life and ministry were a matter of increased speculation around Jesus’ time. If the priesthood that Moses and Aaron established represented the “normal” priesthood established by God’s own law, then Melchizedek’s priesthood represented an act of God’s sovereign freedom to work outside the law. The writers of the Dead Sea Scrolls, believing that the Aaronide priests of the temple had become irrevocably corrupt, seized on this. They saw in Melchizedek a supernatural character who could come and purify Israel’s religious establishment. Early Christians, recognizing something similar in Jesus, noted the connections between Melchizedek’s offering of bread and wine and Jesus’ actions at the Last Supper. At least some saw in him a new Melchizedek, who had come from God to restore Israel’s lost sanctity (Heb 6:20-7:3).

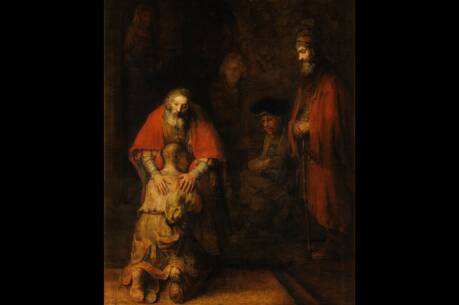

The belief that Jesus was continuing the work of Melchizedek reveals a covenantal meaning to his blessing in this Sunday’s Gospel. The abundance it produced symbolized the new life offered under the reign of God. Luke uses similar language to link Jesus’ blessing over the bread and fish to the blessing over the bread and cup at the Last Supper. Through these actions, Jesus continues the ministry of Melchizedek, offering a covenantal blessing to anyone who participates in the Eucharist.

Eucharistic abundance is real, but not always clear. How often do we, like the apostles, face situations of vast need with resources seemingly as meager as stale bread and a few anchovies? We can trust Jesus’ blessing to have a real effect. With a faith like that of our biblical ancestors, we can find in Christ’s body, blessed and broken for us, the source of everything we need.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Blessed Are You!,” in the June 10, 2019, issue.