Every good work contains the possibility for an encounter with God.

Every good work contains the possibility of an encounter with God. This Sunday’s first reading and Gospel both illustrate this.

She had a sister named Mary, who sat beside the Lord at his feet listening to him speak. (Lk 10:39)

How have your good works attuned you to God’s presence?

How have your good works helped you hear the good news?

In Abraham’s time, visitors were relatively rare, and their arrival could be a cause of anxiety for all parties. A powerful individual could enslave an unprotected wanderer; an unscrupulous traveler could plunder an unsuspecting host. To control the encounter, ancient cultures turned hospitality into a highly ritualized affair. Following these rituals allowed both host and guest to demonstrate their good intentions and to part ways enriched by the encounter.

Poverty was no barrier to exchange. Abraham’s culture likely resembled later Near Eastern civilizations, in which poor guests were welcome if they were good storytellers, if they offered blessings or wisdom or the promise of some future gift. Toward this end, Abraham’s guest offers a prophecy, assuring his host that he will return in a year to find Abraham with a newborn son.

Who would blame Sarah for her laughter? A man rich only in words—who had spent the morning wandering under the desert sun—had announced her pregnancy. Sarah knew what it took to bear a child, and that knowledge closed her mind to the possibility. But Abraham believed and suddenly recognized that his mysterious guest was more than he had first presumed.

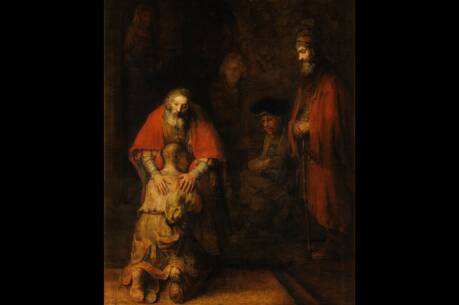

By performing the good work of hospitality, Abraham glimpsed the face of God. The encounter was unexpected, but Abraham had the presence of mind to recognize that something new was happening. He could thus recognize the grace that resulted from the encounter—a deeper relationship with God, a covenant, a family, a long-awaited heir. The good work, though certainly laudable on its own, was only a matrix for a divine encounter.

Although Mary and Martha live in a settled, agrarian culture nearly 2,000 years after Abraham and Sarah, they are clearly heirs to similar traditions of hospitality. Luke, in an effort to teach his community discernment, focuses on the negative example of Martha’s “busy-ness.” This might distract our attention from Mary’s work of hospitality, which took the form of sitting with and listening to Jesus. Through that effort, she engaged with the word of God.

Who could blame Martha for her frustration? Mary’s way of hospitality was unusual in the ancient world, as many commentators note—so rare, in fact, that Martha might not even have seen in the situation an opportunity to listen to Jesus. She was aware only of the good and necessary work a guest required. That very work kept her from recognizing the divine presence she was hosting.

A life of discipleship often includes much knowledge and much action. The content of the faith can take a lifetime to learn, and there is much to do once one commits to the path. We must never forget that the learning, the worship, the works of charity and service, praiseworthy though they might be, are themselves only windows that open onto God’s presence and allow us to encounter his living word anew.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A New Awareness,” in the July 8, 2019, issue.