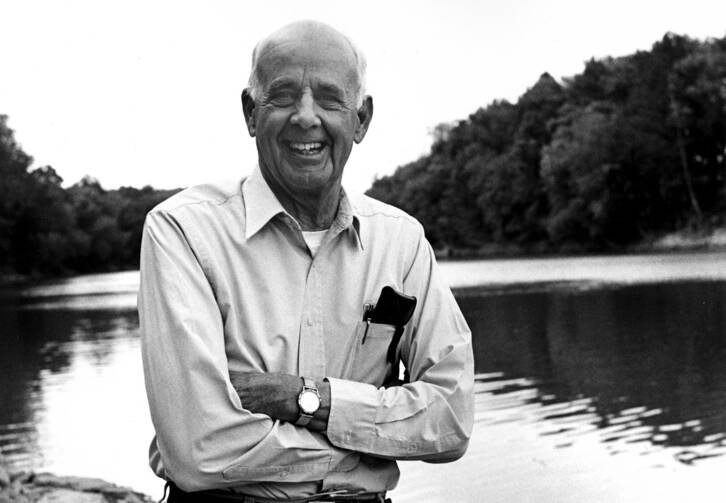

On the road with Wendell Berry

I fell in with Wendell Berry early. At 16, I started visiting an independent bookstore on the Fox River in Chicago’s west suburbs near my high school. I spent many afternoons there, and probably too much of the money I was making working on weekends. They would allow me to stay for hours: crouching to investigate, sitting to read, asking questions. The bookseller was a smart, indulgent woman. She observed my interests and remembered my patterns. My tastes were rapidly evolving from only the religious into modern literature, ecology, poetry and philosophy. Soon I learned that there were implicitly religious people who wrote explicitly about these wider matters.

One day, my bookselling mentor put two books by Wendell Berry in my hands: The Wheel (a book of poems) and Recollected Essays. Right away I noticed their physical uniqueness: They were paperbacks with French flaps; that was new to me. Berry’s longtime publisher is Jack Shoemaker, editor of the volumes under review. In the 1980s, Shoemaker was running North Point Press, which was known for using the paperback French flaps on poetry, novels and essays, and was publishing some of the most interesting writers of the 20th century, including M. F. K. Fisher, Jean Giono and Hugh Kenner. But I digress. She said to me, “I think you should get to know this author.” I bought The Wheel that day, and came back with caddying money for the essays one week later.

The Library of America. 1,702 pg (two volumes) $75

I read those books over and over, and gave copies to friends. Wendell Berry became one of those authors in my life. Perhaps you know what I mean: He was walking a road that drew me, and he was articulating the road that I already sensed I was walking on. At a time when I was also discovering Thomas Merton and biographies of St. Francis of Assisi, I believe it was Berry who taught me to seek solitude, to find meaning in wild places and to know the benefits of being still and small. I have not always followed his advice, but I think my life has been richer when I have.

A few years later, as a college sophomore, I explained to three new friends who Wendell Berry was. They nodded without much interest. Then I added that I had access to a car for spring break and intended to drive to Kentucky to find and meet him. This was suddenly an adventure worth tagging along. I still smile, remembering the four of us meandering the knobs of Kentucky as our friends headed to beaches with beer kegs.

The natural world is Wendell Berry’s primary teacher: its rhythms, its largesse, its mysteries.

This was well before GPS and Internet searches. I knew only two things. The blurbs on book jackets referred to Port Royal, Ky., where he lived with his wife. And there was a woodcut illustration in one book that seemed to be an illustration of his home and farm. We drove from Chicago south, following a map, and made our way to the junction where the map suggested Port Royal was nearby. I slowed to a stop and asked a farmer walking a horse: “Excuse me. Could you point me in the direction of Port Royal?” He pointed to the right-going fork, and we drove a mile in that direction. Then it was almost uncannily easy: I saw on the near horizon a few farms and I pointed to one of them, holding up the woodcut illustration to my friends. That’s it, we agreed.

It was suppertime. I parked the car on the road below the house. There we sat, awkwardly talking among ourselves. “Well, what now?” one friend asked. “I’m not sure,” I said. “Are you going up there?” “Should we all go?” “No, we can’t do that.” “Don’t get out of the car.” There we sat, debating our next move—my next move—until 10 minutes passed and I felt conspicuous.

“He probably sees us down here. He’s going to call the cops,” someone suggested. “Then get up there and say hello!” said another. I finally got out of the car and walked the steps toward the house. I remember a dozen steps up a sloping hill, but I could be wrong because it has been 32 years and I haven’t been back since.

I have read all of Wendell Berry’s more than 80 books. I like the novels; I love the poetry; but most of all, I love the essays.

Stepping onto the porch, I reached the door and knocked. A minute went by, then the door opened. Berry’s wife, Tanya, was standing there. I knew it was her. Anyone who has read Berry’s poems would know Tanya on sight. “Hi,” I said. I motioned down to the car. I think my friends waved from the windows. “I’m sorry that we’re sitting in front of your house. It probably looks strange.”

She didn’t say anything. She gave me a look and smile as if to say that this was brand new, and she hadn’t noticed the car. I went on, “We’re college students from Chicago. I’m just a fan of your husband. Could I possibly say hello to him?”

Then she gave a generous smile, and said, “Oh, that’s unfortunate. He isn’t here. In fact, he’s in Chicago doing a reading tonight.”

I have read all of Wendell Berry’s more than 80 books, and half of those I have read several times. I like the novels; I love the poetry, particularly the “Sabbath poems” that he has written for years on Sundays; but most of all, I love the essays.

There is always movement in Wendell Berry’s sentences.

There is always movement in Wendell Berry’s sentences. He writes about what he has experienced, what he has learned, and always with humility for what he does not know. The natural world is his primary teacher: its rhythms, its largesse, its mysteries. And in the essays, the natural world often reflects how change in humans is also natural, inexplicable and possible. I think this is what many who love his writing appreciate most about Berry, whether they realize it or not. For his Christian readers, this becomes an expansion of what we understand as conversion.

At the time of my introduction to Berry’s essays, I was reading William Wordsworth in school and lines from “Tintern Abbey” must have been in my psyche:

…a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion

One experiences this again and again in Berry: a turning toward reflection that is only born apart from worldly things. I think Berry’s readers understand their desperate need for this, for places that might engender it, and for a way of life that supports it.

For Berry, the world is not one in which spirit and matter are at war with each other. Our bad decisions and habits are the reason for this. For Berry, matter (the natural world) is good: It is what we have done to the world that turns things bad. “We are living even now among punishments and ruins,” Berry wrote in “A Few Words in Favor of Edward Abbey” (one of his heroes), an essay that did not make the cut in this edited collection.

In all of his essays, Berry does not so much find simple pleasures in life as find that pleasure is simple.

In all of his essays, Berry does not so much find simple pleasures in life as find that pleasure is simple. He frequently questions society’s attempts to improve things, modernize or make ways of living more efficient. Those words—improve, modernize, efficient—might as well be in quotation marks whenever they appear in a Berry essay. He doubts them consistently. In “The Way of Ignorance” (Vol. 2) he defines “arrogant ignorance” as “willingness to work on too big a scale.” When life is lived more simply, those living it are apt to be more joyful, peaceful and loving, with basic needs satisfied and in harmony with the land and its creatures.

Provocatively, he writes, “Novelty is a new kind of loneliness” in an essay, “Healing,” that is not included here. Specifically, he writes (among hundreds of possible examples) in “Horse-drawn Tools” (Vol. 1) that every machine or instrument designed for progress or increased efficiency “should be adapted to us [not the other way]—to serve our human needs.” This is exactly the conversation we are finally beginning to have about mobile phones and how they are ruining us.

I recall in college using Berry’s ideas to argue with adults giving me advice on what to do with my life. (We do this to our elders: quote our favorite authors to dismantle the elders’ assumptions!) I was being advised to think big and imagine how I might do great things with my life. I was reading Berry at the time, and his vision for what was great and good was the opposite of big. He wrote about the values of staying put (he had left a teaching position at New York University to return to the family farm), nurturing a small piece of earth with the passion and attention most people bring only to a career, and opting out of what the world calls progress.

“I want to live a small life. By living small and purposefully, I think I can do the most good,” I would say. I probably sounded like Henry David Thoreau, but it was Wendell Berry I was parroting. In these ways he sounds quite conservative, and in the early 1970s, when his children’s generation were hippies, he was conservative, poking fun at the new conformism. He wrote in an essay, “Think Little” (Vol. 1), in 1972: “Individualism is going around these days in uniform, handing out the party line on individualism.” Then he basically predicted that hippies would become baby boomers: “Our model citizen is a sophisticate who before puberty understands how to produce a baby, but who at the age of thirty will not know how to produce a potato.”

Those are really just two themes in Berry’s work, and these volumes are a rich retrospective. A chronology of the author’s life and explanatory notes enrich both volumes. There is also much here on the value of hard work, the meaning of human dignity, the scar of racism in the United States, buying local and eating local. In fact, it is Wendell Berry who first said, “Eating is an agricultural act” (“The Pleasures of Eating,” Vol. 1).

He is not always right. Any essayist worth reading will anger and annoy you from time to time. Berry can be cranky. You will probably find paragraphs and essays in this collection of 1,700 pages to skip over, but not many. His wisdom, and his call to better habits, is too essential. To ignore Wendell Berry is like trying to ignore your grandmother: You just can’t.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “On the road with Wendell Berry,” in the October 28, 2019, issue.