The most unusual feature of “Knives Out”—the introduction of contemporary political tensions into a cheeky Agatha Christie homage—is also its least-satisfying element.

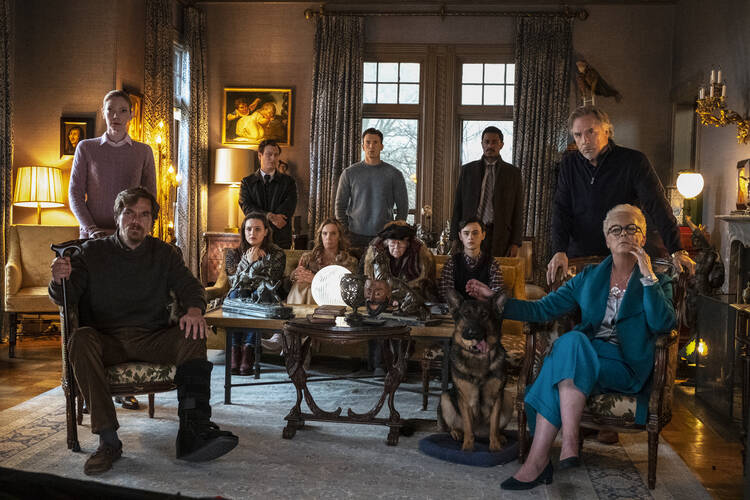

“Knives Out” tells the twisty tale of the mystery author Harlan Thrombey and his fractious family, who gather for the patriarch’s 85th birthday party—at the end of which Thrombey is found dead. Thrombey (his name is a cute tribute to the Choose Your Own Adventure series’ whodunnit, Who Killed Harlowe Thrombey?) lived in a country house made for murder, all secret passageways and artwork made of knives. An unknown employer has sent the legendary sleuth Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) to find out whether Thrombey died by his own hand or by foul play.

“Knives Out” has certain imperfections: The humor is never quite as scathing as it wants to be and relies far too heavily on mild profanity, as if it is inherently funny to see country-house people say “s**t.” Still, mostly, the contraption is solid. It has the perfect house; the perfectly horrible family in which every member has a sordid secret and a motive for murder; and the perfect camerawork, all the usual tight close-ups pinning down the suspects as Blanc confronts them.

“Knives Out” has certain imperfections.

But Blanc is not the center of this mystery—or, as he puts it, the donut hole that fits this donut.

That role is played by Marta Cabrera (Ana de Armas), Thrombey’s nurse. Marta is the daughter of an undocumented immigrant, so any hint of her involvement in his death carries even higher stakes than the family members face. She is enigmatic at first but soon emerges as the one pure soul in a house of snakes.

And here we confront the movie’s weak spot: Marta’s strength.

A story can center on people who genuinely, consistently, know what is right and seek to do it if the people in question are, in some way, weird. The goodness of a strange person can be haunting and challenging: take the homeless trio in “Tokyo Godfathers” or the otherworldly saint in Alain Cavalier’s “Thérèse.” Marta’s problem is not that she is pure and good. It’s that she is pure and normal.

This normal goodness is an explicitly political choice. The film contrasts Marta’s angelic nature with the crass behavior of the wealthy, white Thrombey family. Several of the Thrombeys are Trump supporters who discuss the president at length in arguments not notable for their insights into American political divisions. But even the “woke” Thrombeys are more self-righteous than humble, more self-assured than confused.

Marta’s problem is not that she is pure and good. It’s that she is pure and normal.

Marta is frequently confused, and here is another issue. Throughout the film, she is blown around by her situation, trying to find somebody who can tell her what she should do. Notably, she does not get advice from her mother or sister. The people who give her advice, to which she attends with the diligence we all hope to receive from the objects of our advice, are always powerful white men. Of course, the moral here is that Marta’s own judgment is best of all—as powerful white Blanc (oh, I get it, his name means “white”!, you think) tells her. Only once she has been reassured by a white man that she is “a good person” who should make her own decisions is she willing to do so. This is comfort fiction for white liberals: the Latina as ministering angel, always willing to listen and to help even when we white folks do not deserve her saintly presence.

Even Marta’s one weirdness only reinforces her status as pure lamb. Marta is physically revolted by untruth; more bluntly, she pukes when she lies. She is able to muster a certain casuistry, but this trait still makes her a truth-detecting tool in the hands of more than one character. Whose fantasy is this? Marta’s condition is eerily reminiscent of the slaveholding Romans’ belief that slaves were incapable of lying under torture. In 2017’s “Get Out,” the wealthy white characters’ demand to extract the truths perceived by black people was the engine of their villainy; here, Marta regurgitates her truths in a comic display of virtuous servanthood.

She has no other character traits. To take an obvious example, a movie with more noir in its heart would let Marta have a romantic entanglement with a member of the Thrombey family—maybe the ne’er-do-well son (a surprisingly convincing Chris Evans), maybe the patriarch himself, maybe the art-school daughter who wants to be her ally. But that would make Marta too complicit, too scuffed.

Both the climax and the denouement of “Knives Out” are extremely satisfying. The detective gathers the whole family together to unravel the mystery in a welter of last-minute clues and confessions. The story of what really happened to Harlan Thrombey the night of his 85th birthday comes open like a safe whose dial is spun by an expert cracksman, every detail falling into place.

And the film’s final image is a reminder that justice requires both lifting up those who have been cast down and casting down the mighty. This Gospel message is at once thrilling and—because all of us are the unjust power in somebody’s story—unsettling.

A Christie parody for Trump’s America, where the embodiment of chastising justice isn’t the detective but the scapegoat, is a strange, potentially powerful concept. But why is the avenging angel here so nice?

Correction 12/16/19; 9:40 a.m.: Due to an editing error, the last sentence in this review was omitted; it has been restored.