In God’s kingdom forgiveness is given, not earned

In this Sunday’s first reading, the prophet Isaiah writes, “Our God is generous in forgiving. For my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways, says the Lord” (Is 55:7-8). We humans have an ingrained sense of fairness, which we develop as we compare ourselves to others. Even many animals reveal a sense of being shortchanged if another animal receives more food or attention than they do. This Sunday’s Gospel grapples with the moral difference between the biblical sense of justice and the system of rewards that we have become conditioned to believe represents a “just” compensation.

The end of this Sunday’s Gospel reads, “Thus, the last will be first, and the first will be last” (Mt 20:16). Beyond being a clever phrase indicating a reversal of fates, the line serves a truth beyond rhetoric. It points to Matthew’s key understanding that the “last” or the “least” in society have a privileged place within the kingdom of heaven. The nuances of this lesson are hard to grasp, as today’s parable reveals.

He said to them, “You too go into my vineyard.” (Mt 20:7)

Do you feel invited to work in God’s vineyard?

Where can you recognize a just compensation for believing in the Gospel?

Is Jesus’ message of unconditional forgiveness something you can practice today?

In the parable of the laborers in the vineyard, Matthew complicates the idea of fairness in the workplace and in the kingdom of heaven. In general, employees judge fairness by comparing their employment conditions to those of their coworkers, and not by any individual agreement with their employer. Today’s parable speaks of a landlord who gives a full day’s wage to those who entered the vineyard to work only at the last hour. Commentaries often justify the actions of the landowner, arguing that there is no malice, that he is free to do what he wants with his money, and that he is generous. That sort of logic might miss the point that Jesus was trying to make. The gross imbalance of wages in this parable offended both ancient and modern senses of workers’ rights. The action Jesus describes, however, expresses with clarity the logic of God’s kingdom.

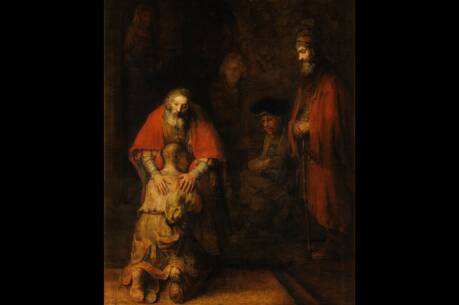

Here and elsewhere in the Gospels, Jesus insists that “the last will be first, and the first will be last.” In other words, in his kingdom forgiveness is an eternal compensation that is simply given, and not earned. Some can find this message of “good news” difficult to accept. Consider the opposite: conditional forgiveness, or none at all, and a tepid response of faith from believers. God’s vineyard, in Jesus’ imagination, is a place where disciples spread the message of salvation by practicing unconditional forgiveness. There is no greater witness to the faith than to forgive; even martyrdom takes second place to acts of forgiveness. In Jesus’ parable, we can hear an echo of the first reading as a gentle whisper, “Our God is generous in forgiving.”

In the larger context, some of the disciples remain fixated on the question of “eternal” compensation. They want to know what is in it for them at the end of their lives. Matthew gives extended consideration to this question, beginning with an episode in which the disciples ask Jesus, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” (Mt 18:1). After nearly two chapters of parables on forgiveness, Matthew concludes the section with an episode that reveals how little the disciples grasped. The mother of two of Jesus’ disciples requests of him, “Command that these two sons of mine sit, one at your right and the other at your left, in your kingdom” (Mt 20:21). In light of such slow change in hearts, Jesus placed his hope in succeeding generations of disciples, and ours as well, to grasp and teach the lesson, “the last shall be first and first shall be last.”