The first of two worldwide Synod on Synodality meetings concluded in October of this year, marking a month of historic firsts. The 365 participants in Rome—Pope Francis among them—included laypeople as voting members for the first time at a synod. The gathering also introduced a new method of deliberation for Vatican proceedings, with members meeting in small groups at round tables, emphasizing listening to each other in addition to delivering presentations.

Commentary from many delegates in the aftermath, ranging from cardinals to clerics to the lay men and women who participated, noted that the church was embarking on a new path of communion.

As voters in the United States approach another presidential election, how can this synodal experience inform the ways that U.S. Catholics engage in political conversation? While the presidential race seems to be heading for a replay of 2020’s Biden vs. Trump, with even deeper partisan rancor, other parts of the political landscape are scarcely recognizable. For example, the question of legal abortion, which the U.S. bishops’ teaching document on the political responsibility of Catholics, “Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship,” has long called the “pre-eminent priority” for Catholic political engagement, used to be focused on Roe v. Wade at the Supreme Court. But abortion has become, since the 2022 Dobbs decision, a thorny legislative question at the state level.

In this complicated political terrain, continuing to identify abortion as the “pre-eminent priority” could confuse more than it clarifies. The question is not only what place protection of life has in our moral teaching and the formation of conscience, but how to give those commitments practical effect. How should we assess the variety of contingent and local factors when choosing which policies to support and which candidates to back? Take, for example, the states that have adopted constitutional guarantees of abortion access, as Ohio did most recently on Nov. 7. How should the vanishingly slim likelihood of achieving better legislative protection for the unborn in these states be compared with the prospect of alleviating childhood poverty to reduce abortion rates—or with seeking a just peace in Israel and Palestine, recognizing the human dignity of immigrants seeking asylum at our borders or the pressing crisis of climate change?

The synod’s patient model of dialogue and listening offers the U.S. church an invitation to engage these questions as opportunities for discernment rather than ideological battles. Rather than expecting an unequivocal answer that “baptizes” one political choice or another, we can hope to respond to the call for political responsibility and collaboration with others in seeking the common good and witnessing to the Gospel.

Here are three key insights from the synod that can help us over the next year of political engagement:

Listening. Perhaps the most valuable lesson to be learned from the synod gathering is the importance of genuine listening. While in previous synods the bulk of time was given to “interventions,” in which each member addressed the entire assembly, usually with a text prepared in advance, this synod asked members to listen to each other in rounds of table discussions involving only 10 to 12 participants, and then to share what they had heard from one another, seeking to discern how the Holy Spirit was at work among them.

How can the church encourage and model such listening on political questions? From meetings of the bishops’ conference down through to the parish coffee hour, what would it look like for us to start by emphasizing that fellow Catholics are seeking, albeit imperfectly, to be faithful to the Gospel? What would it look like to first listen, and then strive to articulate to each other how we each are responding to God in our political thinking, before we reject and correct what we disagree with? Such a witness could be powerfully prophetic and counter-cultural in our polarized political life.

New voices. Bishops made up the vast majority of participants in the October synod gathering. But they were not the only participants—and they were certainly not the only voices heard. This made for some surprising results in the final synthesis document. Of particular significance was a paragraph that encouraged a new process of regular evaluation of bishops; it passed with such a significant majority that it is obvious most of the bishops present themselves voted for it. The openness to this call to accountability suggests that the presence of new voices opened up new possibilities.

What political issues might be surfaced if we heard more from voices on the margins? Surely our conversations would be enriched if the wealthy man met the economically struggling woman who felt she had no option but abortion; if the homeowner heard from the migrants housed down the street; if the college student heard parents’ concerns about raising children in our contemporary culture.

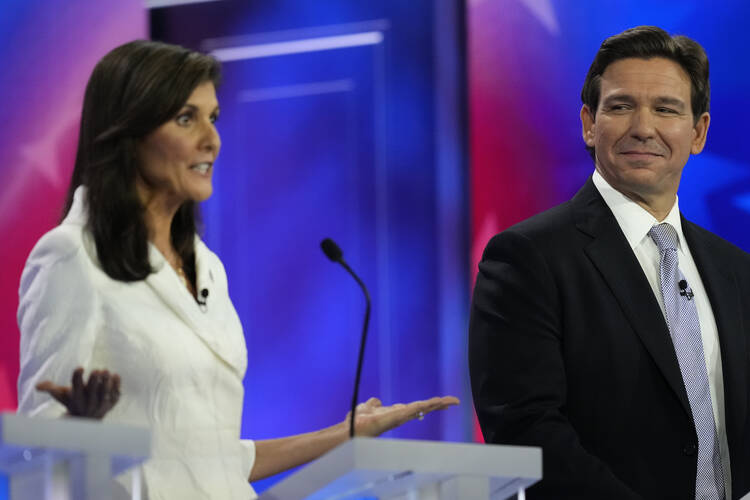

Some of the most striking media images from the synod were of bishops listening carefully to women religious and laypeople. Imagine a similar witness given by an ecclesial dialogue involving both prelates and people in the pews about Catholic political responsibility.

Praying together. A number of the participants in the synod gathering noted their experience of prayerful communion. In a globally diverse church, one commonality was the desire to pray together and to share faith across boundaries of language, background, opinion or standing in the church. Synod members also spent three days of retreat together before they began deliberations. And in his address to the synod’s first plenary assembly on Oct. 4, Cardinal Jean-Claude Hollerich, S.J., reminded participants: “We cannot discern together without praying together.”

We pray from the altar for our political leaders at Mass, but we should also pray in common and in public for the Spirit to guide us in our discernment about the common good. We should pray not only for but with our political and ideological foes.

It is worth noting that the Synod on Synodality ultimately also involved voting—but it unfolded very differently than our voting processes here at home. Disagreement, with some regrettable exceptions, did not boil over into rhetorical gamesmanship; voting aimed at consensus rather than seeking victory. Surely the atmosphere of prayer and the act of praying together had much to do with that.

The last presidential election cycle in the United States was among the most excruciating in our nation’s history for people of every political persuasion, culminating in the nightmare of the Jan. 6 uprising in our nation’s capital. No matter what else they want, Americans want something better this time around. Perhaps if we accept the challenge to listen more intently to more and different voices, and to do so prayerfully, we might finish 2024 with gratitude and pride for the better angels of our nature.