This essay is a Cover Story selection, a weekly feature highlighting the top picks from the editors of America Media.

On Jan. 10, 1999, “The Sopranos” premiered on HBO. It was an exhilarating hour of television, and I could hardly stand waiting an entire week for the next smart, daring, commercial-free episode.

Well, it would be almost a week. I had videotaped the first episode and watched it a few hours after it aired—mostly out of obligation, since I was writing about TV for an alternative weekly newspaper and thought there was a chance “The Sopranos” would be up to the standards of “ER” or “Homicide: Life on the Street.” I was so pleasantly surprised by the quality of the show that I didn’t realize I was watching something that would help kill off shows like “ER” and “Homicide: Life on the Street.” I didn’t realize that “The Sopranos” would, in fact, help end television as a public space and as a vital part of a social democracy.

If “The Sopranos” premiered today, I would probably wait for a long weekend and watch the whole season over a few days. In 1999, I spent a week thinking uneasily about the fifth episode (“College”), in which we see Tony Soprano actually kill someone, and realized that I could not simply enjoy James Gandolfini’s performance as an update of comic TV characters like Ralph Kramden and Archie Bunker. Today, the episode would barely faze me before the next episode would start playing automatically.

Television as a popular medium died 25 years ago. It’s time to mourn.

Another difference was that in 1999, I was telling everyone I knew about “The Sopranos,” which became the talk of the television industry within a few weeks. Today, it might take me months to realize it even existed, and I would mention it only to the few friends who might “get it”—sparing the ones who have said they don’t like violent shows, or shows in which no one is likable, or shows where the protagonist is a middle-aged white guy. I would figure that any show that good is not meant for everyone. After all, watching TV is not like participating in a democracy, right? You don’t have to accept what other Americans like.

The trouble with that attitude is that democracy cannot work without respectful public debate, and public debate has become more and more poisonous as Americans limit themselves to contact with like-minded people—not only in how they get their news but also in how they choose the entertainment that inevitably shapes how they view the world.

Newton Minow, then the chair of the Federal Communications Commission, described the power of television in his caustic “vast wasteland” speech, given to the National Association of Broadcasters in 1961: “It used to be said that there were three great influences on a child: home, school and church. Today, there is a fourth great influence, and you ladies and gentlemen in this room control it.” Minow was speaking when the “big three” television networks (ABC, CBS and NBC) together attracted about 90 percent of the audience on a typical night, and his fear was that the networks would limit their offerings to popular action and comedy programs with little social relevance. “If parents, teachers and ministers conducted their responsibilities” in the same way, he said, “children would have a steady diet of ice cream, school holidays and no Sunday school.”

Things were not as dire as Minow suggested: By the early ’70s, audiences were embracing programs with more substance than “Gilligan’s Island,” and by the ’90s, prime-time storytelling routinely addressed political topics from health care to the death penalty. Then came “The Sopranos” and the rise of HBO: the most expensive ice cream in your grocer’s freezer.

The HBO Bubble

“It’s not TV, it’s HBO” was the subscription-only cable channel’s slogan beginning in 1996, the same year that Fox News launched. Both cable channels offered their own kinds of bubbles, or alternatives to sometimes-abrupt tone shifts of broadcast television in its first half-century. If you stuck to your favorite cable channels, you no longer had to sit through the boring parts of “The Ed Sullivan Show,” which could go from ballet to the Beatles, or spend an evening going from “America’s Funniest Home Videos” to the pilot episode of “Twin Peaks” (which both got huge audiences for ABC one spring night in 1990).

With shows like the extremely violent prison drama “Oz” and the carefully modulated “Sex and the City” (low-key funny, but never sitcom funny), HBO was a haven from the hoi polloi. Despite the urban settings of many of its shows, HBO was like a suburb that had seceded from a noisy metropolis and no longer had to provide services to poor neighborhoods (i.e., less sophisticated viewers). “The Sopranos” and its progeny became known as “prestige” television, a term that evokes Ivy League schools and four-star restaurants.

The first couple of decades of prestige television was dominated by series with anti-heroes or “difficult men.”

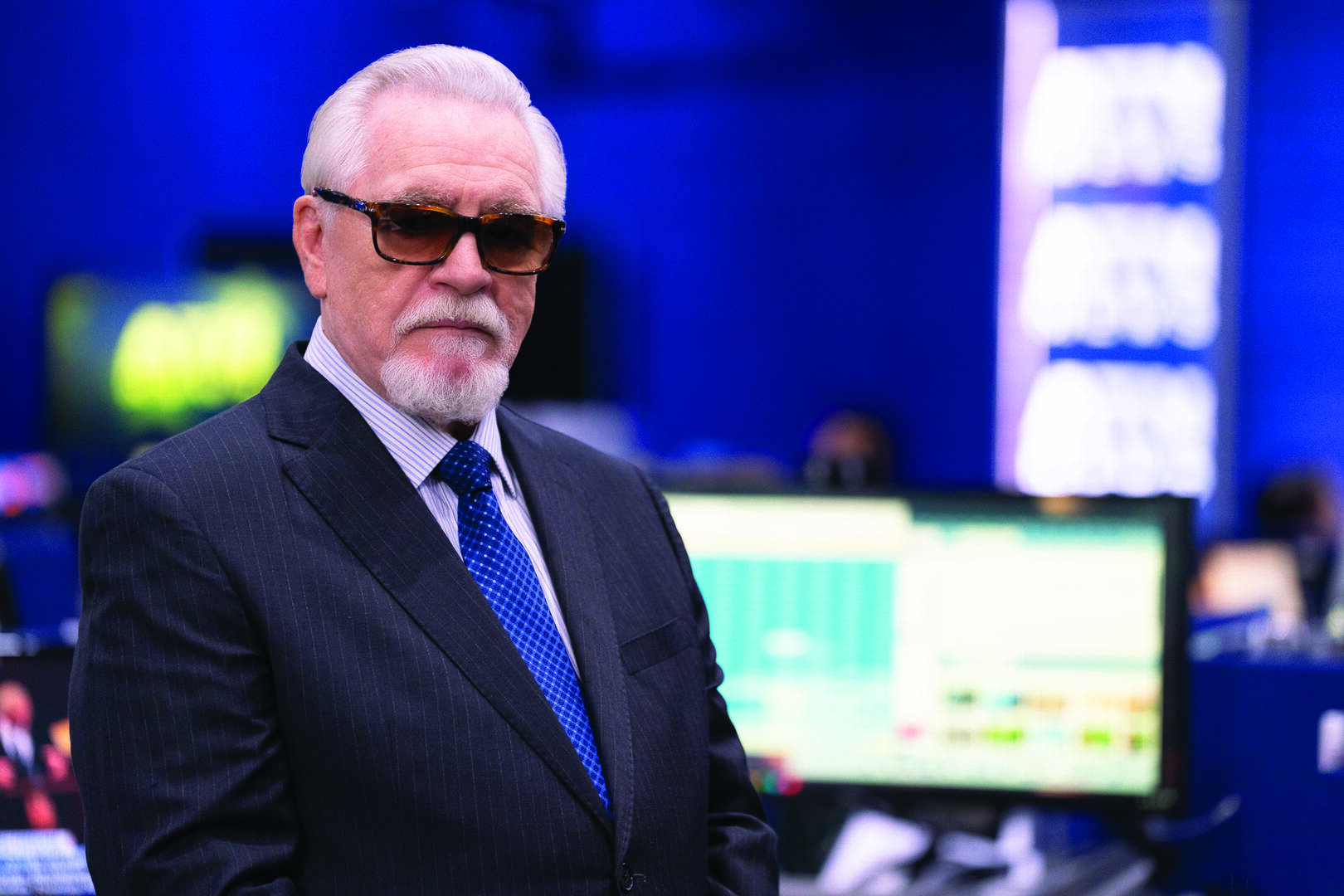

The first couple of decades of prestige television—when it began choking the life out of intelligent broadcast television—was dominated by series with anti-heroes, or Difficult Men, to use the title of an influential book by Brett Martin about television’s “creative revolution.” These series, about narcissistic and even psychotic men ruining the lives of everyone around them, included not only “The Sopranos” but also “Breaking Bad,” “The Shield,” “Dexter,” “House of Cards” and “Ozark.” (There was also the less violent and more hopeful “Mad Men,” as well as a few “difficult women” series like “Damages.”)

Seventy-five years ago, “prestige” television might have meant a Leonard Bernstein concert in prime time, a live production of a play by Eugene O’Neill, an erudite quiz show like “What’s My Line?”, or Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen’s weekly program that aired against the frenetic comedy of Milton Berle. Since “The Sopranos,” the term is more likely to refer to a series about a killer who evades justice over and over again, or a terrible-people melodrama like “Succession” that grinds on for years with a small but devoted audience.

This is fine with most TV critics: David Bianculli, a longtime contributor to NPR, rebutted the idea that television’s “golden age” was in the 1950s in his book The Platinum Age of Television: From I Love Lucy to The Walking Dead, How TV Became Terrific, in which he wrote, “The Platinum Age of Television as I define it, therefore, is the period from 1999 to 2016 and beyond.” In other words, TV only became worthwhile when it abandoned the idea of shared cultural experiences and instead began catering to obsessive fan bases of shows like “The Walking Dead” and “The Bachelor.”

This idea is reflected by the Emmys. During the 20th century, the television awards went to the best shows that were popular; now they go to shows that are popular among the best-educated. “Veep” and “30 Rock” are no better, and certainly no less repetitive, than “All in the Family” and “Everybody Loves Raymond,” but they have a more sophisticated sheen. “Succession” is no better than “ER” or “Gunsmoke,” but its insularity and in-jokes better fit the prestige label.

The self-segregation of elitist viewers has worsened the fragmentation of what was once a national culture.

Bianculli is not wrong to argue that television has matured since “The Sopranos,” and his analyses of how different TV genres have evolved over the past few decades is fascinating. (I certainly wouldn’t trade HBO’s “Deadwood” for a Top 10 western like “Bonanza.”) But many critics who have celebrated shows on premium channels and streaming services seem to have missed that commercial television—ironically, the closest the medium has to a public space—has become much worse. There has been a cost associated with “peak TV,” as the self-segregation of elitist viewers has worsened the fragmentation of what was once a national culture.

The Ups and Downs of Broadcast TV

It would have astonished Americans who watched, say, coverage of the moon landing in 1969 to learn that tuning into the big three broadcast TV networks would cease to become a habit in most households in just a few decades, or that lists of the most-watched telecasts of all time in 2024 would not include anything from the 21st century other than Super Bowl games. Almost as astonishing has been the near extinction of so many prime-time genres that once seemed invincible, including variety shows, made-for-TV movies and even the mighty sitcom.

The fickleness of TV audiences partly explains why broadcast networks cycled through so many trends, but economic considerations were at least as important. In researching historical TV ratings, I was surprised to discover that critically acclaimed dramatic anthologies in the ’50s, like “Playhouse 90” and “The Twilight Zone,” got pretty healthy audiences. But they were relatively expensive to produce, their audiences fluctuated from week to week (depending on the story and the guest performers), and they didn’t do so well in reruns. So the broadcast networks went overboard on westerns, with 28 of them in prime time in the fall of 1959; the more westerns, the cheaper they were to produce, since they could share sets and costumes. This budgetary reasoning was also behind the proliferation of newsmagazines in prime time in the 1990s and reality shows in the 2000s.

Most of the premium cable shows of the past two decades are likely to be seen as dated and pretentious a few years from now.

Despite the mercenary instincts of the broadcast networks, some laudable programming made it to the air and attracted huge audiences. In the ’70s and ’80s, in addition to socially conscious sitcoms like “All in the Family,” there were popular, made-for-TV movies that sparked national political discussions (including “The Day After,” the 1983 movie about the effects of nuclear war that attracted 100 million viewers, and 1985’s “An Early Frost,” about the AIDS epidemic); historical miniseries (like “Roots” and “Eleanor and Franklin”); and religious epics like 1977’s “Jesus of Nazareth.” In 1980, the prime-time soap “Dallas” may have been the most popular show, but the top-rated program one week in September was the made-for-TV film “Playing for Time,” written by Arthur Miller and based on a memoir of surviving the Auschwitz concentration camp during the Holocaust. “Playing for Time” was seen in about 20 million homes on one night, which was more than 20 times the immediate audience for the series finale of “Succession” 43 years later.

Special-event programming began to fade in the 1990s, but at the same time the bar was raised for weekly dramas. With its fast pace and multiple storylines, “ER” was the most demanding program ever to rank No. 1 for an entire television season. “The West Wing” broke the rule that political dramas never attracted big audiences, and “The X-Files” enjoyed the ratings success that had eluded “The Twilight Zone” and “Star Trek.” There were also ambitious series that didn’t make it past one year but showed that commercial television was evolving beyond the usual crime dramas and prime-time soap operas (like “Twin Peaks”; “Nothing Sacred,” about an urban Catholic parish; and the high-school comedy-drama “Freaks and Geeks”). But the success of “The Sopranos,” by showing an alternative to the broadcast networks, stopped this evolution in its tracks. With upscale viewers fleeing to HBO and other pay channels, the big three networks returned to crime, scheduling endless reiterations of “NCIS,” “CSI,” and “Law & Order.”

Entertainment and culture, like politics, has become as balkanized as supermarkets with dozens of brands of bottled water.

Granted, even the best of the popular TV shows during the “big three” era could be called middlebrow rather than high culture, and the historical dramas were not always strictly accurate (neither is Shakespeare), but the same can be said about the “golden age” of Hollywood. Almost all of the films from Hollywood’s first half-century that are now considered worthy of academic study (from “The Wizard of Oz” and “Casablanca” to “Vertigo” and “Some Like It Hot”) were made for mass audiences, often shown with cartoons and Three Stooges shorts. You did not need to join subscription-only cinemas to see them.

“The Sopranos,” which was more popular than just about anything HBO has produced since (except for “Game of Thrones”), will probably be considered a TV classic for decades to come. But most of the premium cable shows of the past two decades, with their niche audiences, are likely to be seen as dated and pretentious a few years from now. And they will seem slow. Last summer, Roz Chast, a cartoonist for The New Yorker, captured the spirit of prestige TV with “Humpty Dumpty: The Ten-Part Series” (“Episode 3: Humpty is born; the wall is built”), showing how a four-line nursery rhyme might be turned into an origin story that could keep viewers glued to Netflix for a weekend.

The Diversity Challenge

One thing about television that has improved, especially over the past 10 years, is the representation of women and of racial and sexual minorities. The original “Twilight Zone,” which ran on CBS from 1959 through 1964, may come the closest to my ideal television series in its willingness to take risks and surprise viewers. But the producers almost always cast middle-aged white men as the protagonists in the anthology series, even as the stories often explored universal themes like the dehumanization of modern society and the fear of mortality. The lack of diversity on the screen is surely one reason the big three networks lost their grip on TV audiences. Even before HBO stepped up its original content, Fox and other new broadcast networks challenged the big three in the 1990s in part by scheduling more shows with nonwhite leads (including the sketch comedy “In Living Color” and the sitcom “Living Single”).

Today’s streaming services and premium cable networks do much better with representation. For example, the science-fiction anthology “Black Mirror” has been notable for exploring “Twilight Zone”-like themes with more diverse casts. Recent non-broadcast series have depicted life for Latinos in Los Angeles (“Gentefied”), Indigenous Americans (“Reservation Dogs”), Orthodox Jews (“Shtisel”), and Arab Americans (“Ramy”), and other shows have shown the religious beliefs of main characters (like the Catholic family on “The Bear”) in a way that the big three networks once shied away from.

Seventy-five years ago, ‘prestige’ television might have meant a Leonard Bernstein concert in prime time or a live production of a play by Eugene O’Neill.

But most of these programs don’t make it much beyond their target audiences and will never achieve the broad appeal of ’70s programs about Black history, like “Roots” or the TV-movie “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman,” or the reach of dramas with diverse casts like “ER” (or even current broadcast series like “Abbott Elementary”). The streaming-TV model simply doesn’t encourage people to watch shows about people of different backgrounds.

In New York City, where I live, one currently popular show is “Only Murders in the Building,” which depicts apartment life in New York City, while viewers in the American Heartland are tuning into the modern western “Yellowstone.” For just about anyone, there are now more shows on television that reflect your own life; the trade-off may be that there is nothing that reflects our common life, or addresses our common concerns.

Entertainment and culture, like politics, has become as balkanized as supermarkets with dozens of brands of bottled water.

The Lost Opportunity of Public Television

The idea that American television can be both popular and worthwhile may have been irreparably damaged by public broadcasting. The creation of public broadcasting in the United States in 1967 shifted fine arts programming like opera, ballet and classical theater to an underfunded, little-promoted network. The commercial networks, which had far more resources to produce and advertise what it once called “spectaculars,” used this as an excuse to largely abandon the fine arts and, then, any kind of common culture at a higher plane than “Dancing With the Stars.” It is difficult to remember, now, that in the ’50s and ’60s, commercial TV could attract big audiences with productions of theater classics like “Our Town,” “Blithe Spirit,” and “The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial,” and could create modern classics like “A Charlie Brown Christmas.”

Cable television once held the promise of taking up this mantle. When there are dozens, even hundreds of channels instead of three bean-counting networks, the thinking went, there will surely be room for serious art, and for programs that appeal to us as human beings instead of consumers. Newton Minow thought as much; in his “vast wasteland” speech, he was optimistic about getting “more channels on the air” and said “television should thrive on this competition.”

But today, public television is still almost alone in airing fine arts, as subscription channels and streaming outlets concentrate on moody dramas that are often high-gloss versions of the same crime stories seen on commercial television. Even worse, all those channels have made it increasingly rare for television to fulfill its promise as a civic tool or public space. Americans still watch the Super Bowl, the Olympics and presidential debates together, but that’s about it.

The political columnist A. B. Stoddard recently wrote about the 40th anniversary of “The Day After,” which had been championed by her father, then the president of ABC’s movie division. “My father…worked in an age of television that doesn’t exist anymore,” she wrote, “one in which TV could still unite the culture, and sometimes even enlighten it. That era feels terribly remote.”

At the beginning of 1999, it was still possible for television to be a uniting and an enlightening force, but instead it broke apart. HBO went one way in January with “The Sopranos,” and broadcast TV took another route that summer with a new fast-and-cheap hit: the game show “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.”

At that point, what Tony Soprano himself said about the American dream could have applied to American television: “I’m getting the feeling that I came in at the end. The best is over.”

[Read next: “The rise and fall of the socially conscious sitcom, from “All in the Family” to “Roseanne.”]