This essay is a Cover Story selection, a weekly feature highlighting the top picks from the editors of America Media.

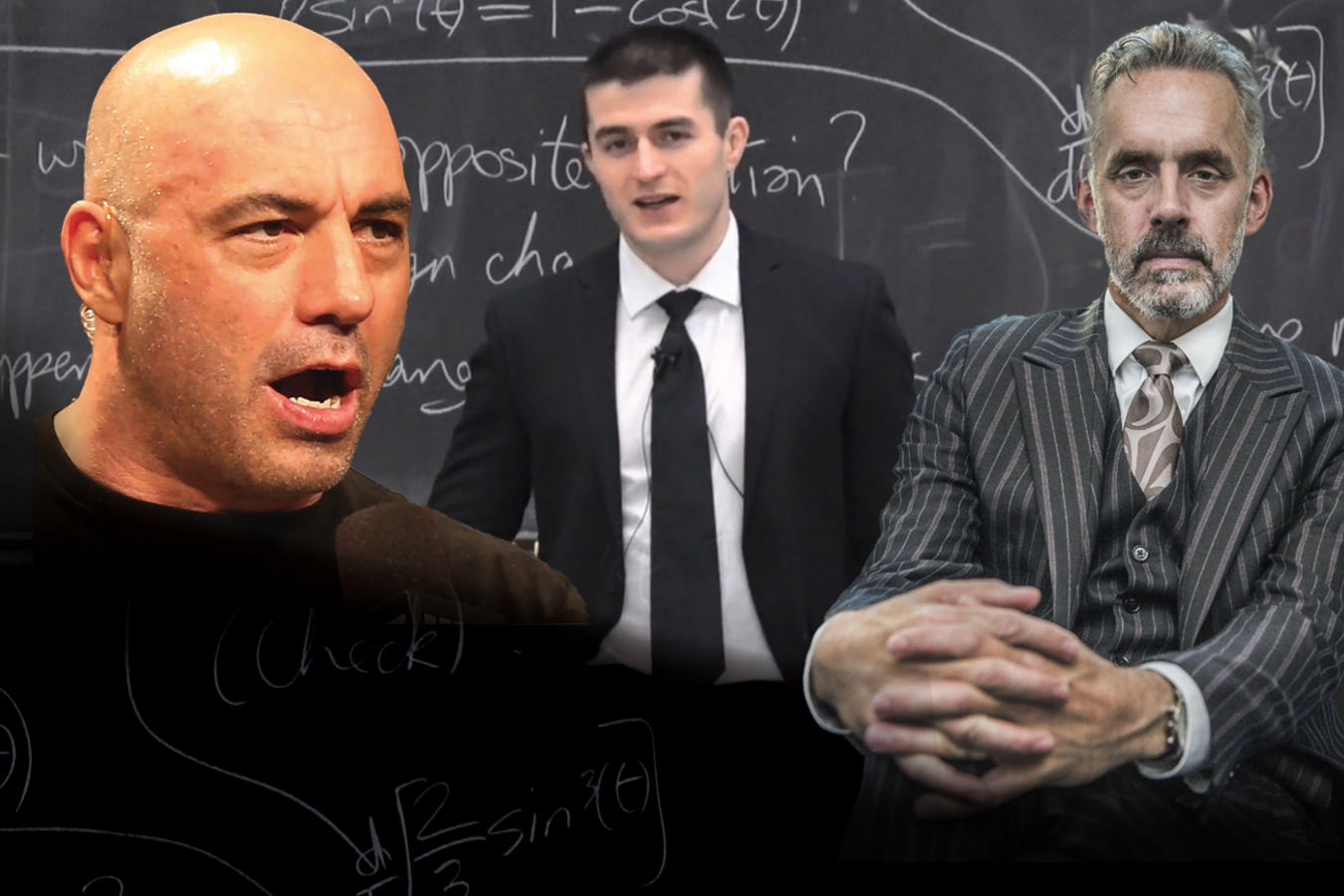

When I started teaching college almost a decade ago, I began hearing the young men in my classes refer to a group of podcasters. The students who brought up these figures admiringly, even adoringly, were usually quiet and sat in the back of the room. Their feeds included Jordan Peterson, Lex Fridman and Joe Rogan—the elder sage, the curious ascetic, the guy to talk trash with over a protein shake. They were then on the verge of becoming household names.

After fairly B-list careers in their primary professions, they have found their callings in the earbuds of the young. Each enacts a distinct but mutually reinforcing persona of white manhood, sponsored by a distinct set of advertisers. They appear on each other’s shows. Together, they inhabit a self-proclaimed “intellectual dark web.”

As I tried to understand what my students were drawn to, I noticed a few things. First, virtually all of the content was extremely long. Podcasts and videos went on for hour after hour, as if in grueling rebellion against the supposition that kids these days need everything bite-sized. Second, at a time when white masculinity is often a target of criticism, they gave a kind of permission for dudes to just practice being dudes together, to think big thoughts, to take nothing off the table.

Through their muscular anti-brevity, these guys carry out a further kind of performance: an insurgency against the political lines in polarized times. They present themselves as aloof from the political categories of the moment, as if in an alternate universe where giving offense is a virtue and nobody gets canceled.

Jordan Peterson is the only one of the three who bothers to publish books. His major writings are less about culture-warring than about Jungian psychology and the practical wisdom of decent living. He encourages readers, for instance, to stand up straight and be kind to animals. But what first brought him most to prominence was his objection, as a professor at the University of Toronto, to a law that added discrimination by gender identity to Canada’s human rights code. He complained that the law would inhibit free speech by compelling the use of a person’s preferred pronouns. Peterson later compared trans identity to a “social contagion” on Rogan’s podcast. In 2022, Twitter suspended him for referring to the actor Elliot Page by his “dead” name and pronoun.

Joe Rogan has defied cancellation for his casual use of a racial slur and his penchant for promoting medical misinformation. Like Peterson, he has promoted anti-trans activists as guests; he has also welcomed trans people on his show. There are interviews in his catalog with the commentator Ben Shapiro and with Senator Bernie Sanders, whose political differences did not hinder Rogan from signaling his support for them.

Lex Fridman exemplifies the persona of category transcendence, of innocent curiosity. He brings on leaders from various religions—Bishop Robert Barron, for example, representing Catholicism—to explain the basics of their beliefs to his listeners. He does the same for political pundits, tech entrepreneurs and scientists. The Israeli prime minister was a guest just before a Palestinian poet. His questions are more leading than he lets on—he seems to enjoy asking guests how they would praise Elon Musk, for instance—but we are told he is merely curious.

The common thread among Peterson, Rogan and Fridman is a studied resistance to commitment—political, religious and otherwise. More than mainstream news broadcasters these days, the podcasters go out of their way to defy political labels. None of the three claims a specific religious affiliation. Over and over, when criticized, these figures insist that they are just interested in the conversation, the dialogue, the hard questions.

In polarized times like ours, there is something refreshing in refusing to choose a side. It’s like being John Wayne on a horse, dealing justice in the way neither the gangsters nor the lawmen want. Accordingly, the podcasters are wildly interdisciplinary, juxtaposing politics and culture wars with deep dives into theoretical physics and ancient mythology.

Among those educating young people on streaming media these days—via podcasts and videos, and even through the brevity of TikTok—the eminent modality is the rabbit hole. Like Alice’s descent into Wonderland, these rabbit holes are journeys of obsession, fascination, impropriety and conspiracy that unsettle the supposed rules of normal life. To get lost in one is to find some relief from the heat and false simplicity of the Boomer-led culture wars. Listen carefully, say the streaming philosophers, but do your own research. People who are coming of age crave complexity, and their favorite content creators know it.

A Return to the Spoken Word

The internet has done something important for philosophy: a return to orality, to the eminence of the spoken word. Many ancient philosophical texts, from India to Greece, took the form of dialogues or monologues, where any written record presented itself as a mere approximation of the original. We know about Socrates’s teachings, including his anxieties about literacy, only because Plato wrote them down. Orality presumes that philosophy is as much a genre of public performance as of abstract ideas, that a persuasive presence is as much a sign of wisdom as what one says. Streamer philosophy thus counteracts the trend of Western philosophy over the past few centuries: an ever-deeper wallowing in the production of increasingly bewildering written texts meant only to be read.

I first encountered Daniel Schmachtenberger when he was onstage at a cryptocurrency conference in 2022. His oeuvre cannot be found in any book, only in hours of monologues and interviews, live or online. Perhaps you caught him on Rogan’s podcast. He has this concept of the “metacrisis”—basically, all the ways the world is falling apart. Over many hours of videos and podcasts across various platforms, Schmachtenberger explains how “we” today find ourselves trapped between the options of unbridled climate-tech-bioweapon chaos and a dystopian, A.I.-authoritarian lockdown. The source of hope is in “sensemaking” our way toward finding a “third attractor,” a technology-enabled option where human decency and planetary ecology still have a chance.

Schmachtenberger represents the more mystical branch of the streaming philosophers, more likely to associate with the “liminal web” than the “dark” one. Until recently, relevant hangouts took place on YouTube channels with names like The Stoa (a reference to the architectural site of much ancient Greek philosophizing) and Rebel Wisdom. Schmachtenberger and his peers, again, claim no specific religious or political confession, but one does feel (and occasionally directly hears) the lingering presence of the New Age philosopher Ken Wilber, the now-elder purveyor of demanding books and workshops offering a “transpersonal” “theory of everything” that unites science, spirituality and experience. Schmachtenberger, for his part, attended Maharishi International University in Iowa, which is associated with the Transcendental Meditation movement.

The streamers induce nostalgia for me as much as anything else. Most of what I read in my coming-of-age years were textual versions of the same sort of thing: highly confident men in militarily dominant societies explaining the world at length. The more abstract the better.

The apogee of this genre was the 19th-century German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel. His writings are lengthy, impenetrably dense and supremely confident about the workings of the universe. Many of these texts are actually notes from his lectures transcribed by students. I know the appeal of this sort of thing; my first book, a zealous history of proofs for the existence of God, cribbed its core idea from some of those lectures. If Hegel were alive today, I bet his disciples would be encountering him not primarily in books, not on TikTok, but on the vast monologue-friendly expanses that YouTube and Spotify afford.

For Hegel, all philosophy is actually history. Ideas develop in evolving relationships to each other through sequences of dialectic: thesis, antithesis, synthesis. To philosophize, then, is not solely to apprehend certain ideas; it is to stand above and beyond all ideas and observe their swirling development. Polities that mattered to Hegel, like Prussia, were the agents of history. Non-European peoples, peripheral to his story, are people without history. China has no real history, he believed, and stateless people have no history. Their fates do not ultimately matter. They are expendable, philosophically speaking, despite whatever they might say about themselves.

Hegel saw Napoleon marching on Jena as the “world-soul,” the angel of history; Lex Fridman has been similarly obsessed with the proposed cage fight between Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk. For the YouTube Hegelians, the agents of history worth caring about are tech-startup founders.

Like Hegel, his online successors seem to think that everything important is big—the trends that are all-consuming and inescapable. In an age like ours that is so full of division and polarization, identity politics and information overload, these metanarratives offer a simplifying sort of complexity. The point is not which side of a culture war wins or loses, because both sides of the dialectic are necessary participants in the process of history discovering itself. As Ken Wilber’s “integral theory” would suggest, they are just squares on a quadrant, points on a map of possible positions. No particular position matters, ultimately, but only the map, the view from nowhere that can see how they all interact and where they are leading.

The price for achieving the view from nowhere is time. Schmachtenberger’s monologue introducing the third attractor—the first of two parts—lasts almost three hours. He likes to insist that properly understanding one of his ideas will take multiple hours and several sessions. I am astonished that anyone can talk into a camera for that long and do so coherently, and that tens of thousands of others show up to watch. But they do. The amount of time spent with the philosopher is inseparable from the ideas he uses that time to convey.

The internet has done something important for philosophy: a return to orality, to the eminence of the spoken word.

Duration is no accident in the Hegelian tradition. The longer a philosopher can draw you into his universe—with its extensive terminology and opaque phrasings—the more you drift from identification with the world of mere particulars, mere location, mere identity. You become a philosopher-king in a universe of philosophical sovereigns. You see the universal and become a citizen of it. Length and difficulty are the table stakes, the hard-won ante that keeps disciples in the game and renders them trustworthy. These videos serve the same time-gobbling purpose as a heavy and difficult text.

Plus, more time means more ad views.

Hegel’s ideas proved useful for calamities. Writing certain places and peoples out of history surely eased the self-deceptions necessary for colonial regimes. Among the “Young Hegelians” who built their ideas on the foundations of the master was Karl Marx; his metanarrative of class struggle has justified regimes willing to let millions of their own people die for the cause. The centrality of what became the German nation in Hegelian thought prepared the way for Nazi mythology. Once you understand the dialectic of history in the Hegelian sense, nothing else really matters, and human life can seem expendable.

I do not mean to malign the YouTube Hegelians through such associations, but the associations are cause for caution. They love to talk about complexity theory, but they tend to ignore the complexities and differences among human cultures. They abhor the claims of identity politics and rarely talk about sexism or racism or ableism, except in ridicule. In their grand storylines, such trifles ultimately do not seem important. The dialectics at play will be absorbed into what is really real: tidal waves of “exponential” technologies and epochal shifts, such as life extension and space travel.

The philosophers can claim innocence from the fray of culture wars because they have their eyes on the meta-wars. And they are particularly influential in the world-colonizing subculture of tech startups.

Going Meta

When Mark Zuckerberg renamed his company from Facebook to Meta in 2021, he did so under duress. Especially after the 2016 election, he became the leading villain of a “techlash.” Politicians, journalists and even some Silicon Valley peers accused him of destroying democracy at home, enabling genocide abroad and committing a host of other wrongs. A former employee, Frances Haugen, released troubling internal documents and testified about them before Congress. The language of “meta” offered an escape, a way up and out. Zuckerberg made the rounds on Joe Rogan and Lex Fridman’s podcasts.

Many teenage millennial nerds like Zuckerberg (and me) learned about meta-ness from Douglas Hofstadter’s glorious 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. It is also a favorite of Schmachtenberger, who features the book at the top of his recommendation list, and, reportedly, Meta employees consulted with Hofstadter during the company’s rebrand. Hofstadter argued that “going meta” is a kind of law of nature, as well as a formula that recurs in mathematics, art and music. To change the frame of reference, he added, is to change the set of possibilities. When you shift from the individual melody to the symphony, or from binary instructions to JavaScript, the rules of the system change.

Long before Hofstadter, the language of meta entered the Western canon through Aristotle’s book Metaphysics. Aristotle did not actually name the book that; a later editor simply attached to it what seemed the most obvious possible title. “Meta” means “after” in Greek, and this work was in the catalog after the book called Physics. But the prefix took on a life of its own. Metaphysics discourses on the nature of being, causation and God—the conditions of possibility for everything else. Thus, to speak of the meta has become not a mere matter of sequence, but also one of transcendence. It is a claim to move from one level of reality to a more fundamental one.

To speak of the “metacrisis,” then, is to claim access to a crisis more real than reality appears to most of us. Going meta means shifting attention away from the problems of politics and culture, away from the world we read about in the news. Rather than fixating on election interference or genocides, Zuckerberg wants us to fixate on a future occurring in virtual worlds, as his company’s “metaverse” products seek to enable.

The YouTube philosophers believe that everything important is big—the trends that are all-consuming and inescapable.

Jordan Hall, a tech entrepreneur and streaming philosopher, is with Schmachtenberger one of the leading theorists of the metacrisis. He speaks of it in terms of two distinct sets of rules: Game A and Game B. The distinction, we are told, takes many hours of content consumption to comprehend. But as near as I can grok it, the idea is that Game A is the dominant way of the world (acquisitive, competitive, self-destructive) and Game B is an orientation that prioritizes collective flourishing (creative, coordinated, coherent). Maybe Game A was working well for a while, but it runs into trouble because of “exponential” technologies—things like the internet and artificial intelligence, whose effects seem to accelerate and transform everything beyond anyone’s control.

The Game B philosophers have a technique for putting the culture wars in their place. Calls for undoing racism and sexism through social movements, for instance, are just Game A thinking. While Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis oppose feminists and antiracists with legislation and polemic, these philosophers do it with their transcendence—simply shifting attention elsewhere, away from the supposed present and toward what is just over the horizon. When one of the rare non-white streaming philosophers, Vinay Gupta, attempted to raise questions of race and colonialism in Game B discussions online, he experienced hostility and censorship from the community there. The leading voices seemed unwilling to challenge the prevailing behavior. Gupta characterized Schmachtenberger, for instance, as “a spineless s—bag on race issues.”

The metacrisis playbook has been particularly visible since the release of the artificial intelligence chatbot ChatGPT. Tech entrepreneurs and investors have rallied around a science-fictional framing of the problem: Large-language models, which learn by analyzing huge amounts of digital text, are an exponential technology that will change everything, and policymakers should start taking responsibility for addressing the catastrophic threats that the supposedly intelligent technologies pose. This is what Sam Altman, the chief executive officer of ChatGPT creator OpenAI, has preached on his roadshows on Capitol Hill. Technologists can thus present themselves as the angels of history, the sources from whom the forces of true importance will come, while passing off the responsibility for their products’ harms to the geriatric politicians.

Meanwhile, tech critics like the former Google ethicist Timnit Gibru see the framing of future catastrophe as a distraction. We have enough problems with A.I. already, they say, and we know what they are: racial discrimination, evasions of accountability by decision-makers, corporations profiting from others’ creativity and an underground network of exploited human workers propping up the appearance of automation. When C.E.O.s point attention to the meta, the worry goes, they are turning regulators’ eye away from the actual injustices going on right in front of us.

In the light of the metacrisis, actual crises become harder to see. Weavers of abstraction obscure the agents of power politics, yet they come together around Joe Rogan’s mic.

Philosophy and Power

In early 2022, Lex Fridman announced: “I will travel to Russia and Ukraine. I will speak to citizens and leaders, including Putin.” He went on: “War is pain. My words are useless. I send my love, it’s all I have.”

Fridman was born in Soviet Tajikistan and claims family members on both sides of the Russian-Ukrainian border. His reflections on the war there have been particularly heartfelt and tortured, even for him—the rare public figure who regularly speaks and invites others to speak about love and hate. He seemed to place great hope in the peacemaking potential of an interview with Vladimir Putin; repeatedly, he would ask guests for advice on what to ask. He seemed to imagine—in a sweet sort of way, really—that with the right kind of conversation, the fighting might end.

He traveled to Ukraine and described visiting the war’s front. The interview with Putin, however, did not materialize. The war rages on. Echoing Plato’s failure to reform a Sicilian despot with philosophy, once again philosophy could not corral political power. As Plato and Hegel found in their own careers, philosophy’s easiest path to political relevance is to concoct elaborate justifications for the powerful. This appears to be the role that the streaming philosophers are performing, not on behalf of some political party but for the corporate tech elite.

What do these self-described “heterodox” thinkers really believe? Perhaps it is more difficult to pin down an oral tradition than a written one, though that is less the case in a universe where every thought becomes a video on the internet and A.I. can transcribe it all. The streaming philosophers discussed here harbor a general skepticism of liberal institutions, such as government regulators, public health authorities and salaried journalists. During the Covid-19 lockdowns, they generally erred on the side of vaccine “skepticism” and whatever else might upset the designs of Dr. Anthony Fauci. Today, Lex Fridman invites guests to ponder the harms of “woke”-ness. And Jordan Hall has flirted with the right-libertarian school of propertarianism, which privileges the right to property over all else.

They can claim innocence from the culture wars because they have their eyes on the meta-wars.

I asked Hall about his relationship to the culture wars over dinner at a conference we both recently attended at Harvard University. As a conversationalist around a crowded table, he was alternately pensive and jovial. But he said he would have to think about my question. The next morning he took me aside and said that the political debates of the moment are “not the hill I want to die on.”

Through the media of interviews and monologues, the philosophers themselves seem anxious to maintain plausible deniability with respect to any given position. Their calling is the bottomless sensemaking. Fridman seemed to believe, with respect to Vladimir Putin, that if the right men get together and have the right conversations, the great problems of the world can be solved. And yet he and his fellow philosophers have a kind of parasitic relationship to the culture wars they claim to transcend, because it is by enraging the partisans that they attract attention to themselves and their advertisers.

In 2022, David Fuller, founder of Rebel Wisdom, went on a retreat in India and decided to close down his platform. This move seems in tune with the anti-institutionalism and ephemerality of streaming philosophy. Yet in a series of essays and interviews, he lamented what had become of the movement he had helped build. Fuller laments that Jordan Peterson, whom he once admired, “is now little more than a boilerplate conservative commentator.”

Fuller described a kind of capture that streaming philosophers often fall for as they chase the dollars and dopamine rushes of online virality. “If you’re outside the institutions,” he explained, “you’re dependent on your audience, and audience feedback becomes a warping factor.” A willingness to challenge certain political pieties can turn a person into an uncritical devotee of the opposite pieties. Probing the uncertainties of a pandemic in public can lead to obsessive anti-vaxxery.

As Fuller considers next steps in his own career, he says he is interested in projects focused on masculinity. This has been the central topic for most of these streaming philosophers all along, though they have rarely acknowledged it as such. I mentioned to Hall that I considered him a role model for young men in particular, and he said he had not thought of himself that way. Yet he agreed that nearly all his public conversation partners happen to be men, just as nearly all the guests on Lex Fridman’s podcast are. Perhaps a more explicit examination of masculinity might help them recognize their interests as dependent upon the particular perceptions of a certain class of experience.

The world does need more conversation across dividing lines. I consider it a testament to my students and other young people who follow these figures that they crave this stuff: long conversations against the culture of brevity, and ideas that challenge the homogenizing pressures of a polarized time. But there are other lessons I hope my students learn—lessons that tend not to come up when tech founders are presented as the angels of history. Try to see the world through the eyes of the poor, not just the powerful. As much as you stay open-minded, be willing to commit.

It should come as a relief that humankind still has an appetite for depth. But is the depth we need to be found in rabbit holes?

[Correction: A previous version of this text misspelled Ken Wilber's name as Wilbur. It has since been updated.]