Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of columns by James Keenan, S.J., on contemporary issues in moral theology.

From Palm Sunday to Pentecost, I keep my eyes on the Upper Room.

In John’s Gospel, we hear that “for fear of the Jewish leaders” (Jn 20:19) after the death of Jesus, the disciples gathered back in the space that Jesus reserved for his last Passover with the Twelve. But fear does not seem to be the enduring reason why they kept returning there. If you fear being caught, you don’t return to the same place every day; besides, after the crucifixion, we do not see any indication of a larger manhunt.

I think the disciples went to the Upper Room to grieve and (in time) to share the consolation of the Resurrection until the coming of the Spirit. In fact, aside from John’s mention of fear, the evangelists (including John) are largely in agreement on this point.

In Mark’s Gospel, the Eleven are gathered in the Upper Room, where, we are told, they are “mourning and weeping” (Mk 16:10). Mary Magdalene knows they are there and reports to them that Jesus is alive, but they do not believe her. Two more come to report to those in the Upper Room that they met Jesus on the road, but again, they do not believe. Later—and we do not know how much later—Jesus himself comes to the Upper Room. Once the Eleven recognize him, he rebukes them for not believing the reports, but then commissions them to preach and ascends to his Father (Mk 16:11-20).

In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus’ disciples grieve in many places, but especially in the Upper Room. We hear that on that Sunday, the women—Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James and the other women—discover the empty tomb and encounter two men “in dazzling clothes” who tell them that Jesus has been raised (Lk 24:4-6). They run to the disciples in the Upper Room, but the grieving disciples do not believe them. Peter then runs to the tomb and is amazed that it is empty (24:6-12).

Then comes the encounter at Emmaus, where two disciples are described as “looking downcast” (Lk 24:17). These two have already left the Upper Room, where they heard the reports of the women and of those who went to check the tomb. Jesus calls these two “foolish” and “slow of heart to believe” (24:25). In their shared grief, they still do not recognize him as he tries to open their eyes by recounting from the Scriptures. Finally, in the breaking of the bread, they recognize him; the Lord vanishes and the two rush back again to the Upper Room to tell the Eleven. As they enter the room, the Eleven tell the pair from Emmaus that the Lord has risen and appeared to Peter, and then the two make their report (24:17-35).

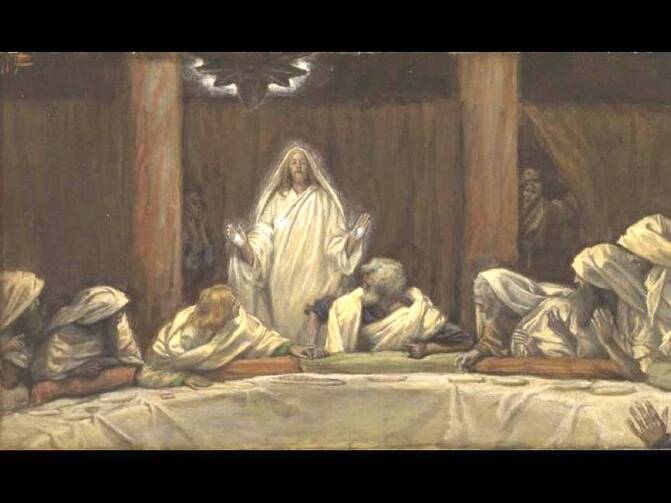

Just then, Jesus appears. They are startled, terrified. But Jesus extends to them his peace, eats fish with them and tells them to stay in Jerusalem because he is “sending upon you what my Father promised” (24:49). He walks to Bethany and then ascends.

In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke notes that after the ascension of Jesus, the Eleven return to Jerusalem and immediately go to the Upper Room, where we are told they were staying “together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers” (Acts 1:14). Luke makes a point that they are there for days (Acts 1:15). When the Pentecost occurs, again, it seems as if they are again in the Upper Room (2:1-2).

In John, there is a different chronological order, but still a lot of grieving—and then consolation. Mary Magdalene discovers the empty tomb and reports the missing body of Jesus to Peter and John, the beloved disciple; they rush to the tomb and then return to their houses. Mary returns to the tomb and grieves outside, distressed not only that Jesus has been put to death but that now even his body has been taken as well. The Gospel refers to her weeping four times, with both the angels and Jesus asking, “Woman, why are you weeping?” (Jn 20:13, 15).

Jesus approaches Mary in her grief, but like the two in Emmaus, she does not recognize him until he calls her by name. She clings to him; he tells her to stop holding on, and commissions her to tell the disciples. Jesus later goes to the Upper Room and breathes on the disciples. He returns a week later to reveal himself and his wounds to Thomas (20:18-31).

In short, the Upper Room serves as a shared space for mourning and gathering reports. The disciples’ grief was not an obstacle to them recognizing Jesus, but rather, the passageway itself to the recognition. Through their grief, they became more vulnerable in their love for Jesus, which enabled them to recognize his risen, vulnerable presence. These words—grief, vulnerability and recognition—are thus inextricably linked to the Pentecost story and, in particular, to the role the Spirit plays in their lives and our lives in the church.

It makes sense to me that they are grieving for a length of time in the Upper Room. After all, they all ran away, except John, Mary the Mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene and a few other women. Where would they know to go except for the place that they first gathered for the Passover meal? And there they would be reunited and learn what they missed in their flight.

Still, I think they went to the Upper Room to find one another, to learn what had happened, and subsequently to grieve and share in their unbelievable shock. Once they do this, they begin to be consoled. I suspect the first few days were pretty messy. The Crucifixion, by all reports, was barbaric: a late-night arrest during Passover, a sham trial, a crowd crying for his death, a humiliating, exhausting procession up to Golgotha. And then a naked nailing to a cross, a crown of thorns and a lance through the side. Veritably grotesque.

What was the Upper Room like for those days, as the whole story was told? What was it like when they heard the details? What was it like when Jesus’ mother arrived there? After every one of them but John had abandoned her son, how did they approach her? How did Peter? What was it like when she and Mary Magdalene and John told them about the crucifixion? How did they react to hearing about the nails, the spittle, the crown?

There in that Upper Room, they learned how vulnerable Jesus was every step of the way. Did they hear how attentive Jesus was, even from the cross—to the thief, the centurion, to his beloved disciple, to his mother? How did they react when they heard about him crying to his Father or breathing his last?

Later, how did the Eleven feel when they found out from Mary Magdalene that Jesus was raised? Or heard the reports from the two at Emmaus? One suspects that they must have been awfully afraid. And one can only imagine the fright they felt as Jesus himself entered the room.

I suspect that when he said “Peace,” they welcomed it. When they saw the wounds and saw him take food again in the very last place that they saw him eat, they realized something entirely new was happening. After all, that room was where he broke the bread and shared the cup, where he had stripped so as to wash their feet, where he made himself a servant to them. In fact, he told them to do what he had done: serve with vulnerability.

I suspect at some point after the appearances but before the Pentecost, they decided to break the bread and drink the cup as he did, but now in memory of him. I suspect, too, that they began to wash one another’s feet. I suspect all this happened in the Upper Room.

At some point it clicked. They would be his disciples in a new way. There would be no more running away, no more competition. Instead, they would each meet their own Jerusalem later on. In that Upper Room, they decided that they had to heed him unlike ever before.

A coda: We moral theologians do our work differently today from how we did years ago. We are more biblical and theological than we used to be. And we use certain concepts in very fundamental ways. Over the next couple of months, I hope to introduce you to some of these concepts, like vulnerability, recognition, grievability, synderesis, conscience, prudence, collectives, intersectionality and more. But for now, I simply ask that you think of vulnerability as Christ-like. The vulnerability of Jesus as he enters the Upper Room, revealing a self full of compassion, offering reconciliation and empowerment. It is a very capable vulnerability. There is nothing precarious about it.