One would be hard-pressed to find an author or illustrator who has made a greater contribution to Catholic children’s literature than Tomie dePaola. His signature style, which has been compared to the bold lines and solid colors of stained-glass windows, has illuminated the lives of the saints, the stories of the Bible and the experiences of children in ways that draw young readers into a world of faith and beauty.

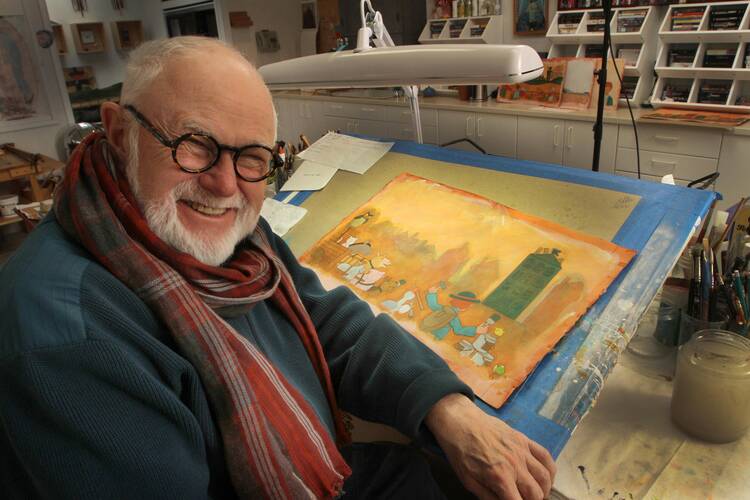

As an accomplished fine artist and liturgical artist, dePaola was well aware of the tradition in which he was working when he took up sacred topics, as he notes in the preface to Saint Francis: Poor Man of Assisi: “I was determined, some day, to recount the tales, in words and paintings, of the two saints [Francis and Clare]. Not an easy task! After all, it meant following such geniuses as Giotto, Cimabue, Simone Martini, Thomas of Celano, G.K. Chesterton, and Nikos Kazantzakis, to mention a few.” DePaola clearly considered his picture-book illustrations and storytelling just as consequential as any of his fine art pieces. As he told America in 2018, “It’s very hard work and I take it very seriously, and especially since it’s really aimed at children. Only the very best is good enough for children.”

Although dePaola did not consider himself a practicing Catholic in adulthood, he continued to recognize beautiful stories in the church through his work. DePaola described the purpose of books like Saint Francis and Mary, the Mother of Jesus as making sure that “these meaningful stories be available for all children in beautiful formats with well-appointed pictures.” He introduces children to the Western artistic tradition with images like St. Christopher struggling across the river with the Christ Child on his shoulders, which echoes a fresco in the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna. He incorporates rich symbolic imagery, as when on the book jacket of Mary, Mother of Jesus, he follows medieval tradition and depicts the Blessed Mother as the New Eve, holding an apple.

Thankfully, many of Tomie dePaola’s books are still in print. DePaola’s death in 2020, however, leaves a gaping hole in the world of Catholic picture books. The situation is similar to that which Dana Gioia lamented in his 2013 essay “The Catholic Writer Today.” After wondering why a new generation of Catholic fiction writers had not arisen to replace the likes of Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy, Gioia explained that these writers represented not a renaissance, but something new: “There was no earlier American Catholic literary tradition to be reborn.” I would like to suggest that while Tomie dePaola might be the grandfather of the Great Catholic Picture Book, we are still awaiting anything like the mid-century flowering of the Catholic literati in the world of literature for young Catholics.

Catholic Cultures and Customs

Tomie dePaola was born in Connecticut in 1934, and at the age of 4 announced that he would grow up to write and draw books for children. On the way to achieving this goal, he received advanced degrees from the Pratt Institute, California College of Arts and Crafts, and Lone Mountain College. He taught art and created fine and liturgical art as well, and when the opportunity arose, he brought all this experience to bear on the images in his children’s books.

He was inspired to tell the stories of the saints in part by the spiritual writer Caryll Houselander. As he said in a 2009 interview, “She made the statement once that people should publish these wonderful legends and stories about the saints because they read like fairy tales. I said, ‘Oh, that’s a very interesting idea. I think I’m going to try that.’”

Over his long career, dePaola helped children to see the broad range of cultures and customs that accompany the Catholic faith. The Legend of the Poinsettia and The Night of Las Posadas celebrate Mexican traditions, while The Legend of Old Befana and Strega Nona’s Gift explore Advent and Christmas traditions from dePaola’s own Italian heritage. An Early American Christmas highlights some German Christmas traditions—including the Christmas tree and Christmas cookies—that have spread into wider American culture, and imagines how one family’s faithfully living out their Christian traditions has the potential to change the hearts of their whole community.

Intentionally yet unobtrusively, dePaola prepares his young readers to recognize and appreciate the Catholic Church’s rich artistic heritage when they encounter it later in life. In St. Francis, the dust jacket illustration is reminiscent of Giotto’s St. Francis Preaching to the Birds. In the author’s note in The Three Wise Kings, dePaola writes, “In this book, I have chosen to paint the mother and child in the traditional pose referred to as ‘Seat of Wisdom, Throne of Justice.’ This pose was frequently used in Romanesque paintings of the Adoration of the Kings.” In The Clown of God, which also helps children see that God rejoices in whatever kind of gift they might offer him (even juggling!), dePaola uses elegant architectural details and framing and draws the statue of the Virgin and Child in the final pages in the style of the Sienese Renaissance. A recognition of the power picture books can have in a child’s formation informed these efforts. As dePaola told Publishers Weekly in 2013, “A picture book is a small door to the enormous world of the visual arts, and they’re often the first art a young person sees.”

Several of dePaola’s books, while not explicitly religious, depict the beauty of family life. In Nana Upstairs, Nana Downstairs, dePaolareminisces about his Sunday visits to his grandparents’ house, where his great-grandmother also lived. The love his young protagonist has for his great-grandmother, Nana Upstairs (who as dePaola mentions in the author’s note, “was my very best friend when I was four years old”), and his learning to deal with his grief at her death highlight the great depth possible in multigenerational relationships. Similar themes appear in Tom and Now One Foot, Now the Other, both of which focus on a child’s interactions with his grandfather. The Baby Sister also includes a grandparent (this time one who is more difficult to get along with), but unlike many books targeted at new older siblings, The Baby Sister focuses not so much on the difficulties of life with a new baby, but instead on the joy that a baby brings to the whole family, older siblings included.

Along with his joyful depictions of marriage and family life, dePaola also shows clergy and religious in a positive light—and not just those priests and religious who are already saints. Though Christmas Remembered, which dePaola hoped would appeal to “all ages,” begins with fireplaces for Santa and new television sets, he also recounts a Christmas spent in Santa Fe (the inspiration for his book The Night of Las Posadas) and two spent with different groups of Benedictines. The descriptions of the joy and beauty of life and liturgy in these communities humanize religious life for those who live outside the cloister walls. One of my favorite moments in all of dePaola’s work comes in The Night of Las Posadas, when Mary and Joseph miraculously appear, telling the priest who is organizing the Posadas that they are “friends of Sister Angie.” The sister’s prayer before the Holy Family is one any child could pray: “Oh, Maria. Oh, Jose, my heart will always be open to you so that the Holy Child will have a place to be born.” I can’t imagine a better explanation of the vocation of a religious sister.

In search of the transcendent

There are a few truly wonderful Catholic picture books out there. Josephine Nobisso’s trilogy, The Weight of the Mass, Take It to the Queen, and Portrait of the Son, come to mind. Carey Wallace’s Stories of the Saints, accompanied by Nick Thornborrow’s striking illustrations, deserves credit for its straightforward and engaging exploration of saints’ lives. Katie Warner and Meg Whalen have teamed up to create This Is the Church and The Tiny Seed: A Parable, the second of which would be at home next to the best picture books anyone is publishing today, Catholic or secular. Haley Stewart, editor of the new Votive children’s imprint from Word on Fire, has consistently emphasized her commitment to championing beautiful picture books.

“A child’s taste is in formation,” Stewart suggested on the Votive podcast, “So we should be offering these opportunities to encounter things that are really beautiful as often as we can, because that’s how their taste then gets formed.”

Still, a perusal of one’s local Catholic or Christian bookstore is likely to be disappointing if one is looking for numerous books of the artistic and literary quality we came to expect from Tomie dePaola. There are many wholesome books, many sweet books, many books that are faithful to the Magisterium…but far fewer whose texts or illustrations—let alone both—could rightly be judged as transcendent in the way dePaola’s feel to so many people.

Dana Gioia, in that 2013 essay, wrote: “Whenever the Church has abandoned the notion of beauty, it has lost precisely the power that it hoped to cultivate—its ability to reach souls in the modern world.” Do we really wish to cede this power when it comes to reaching the hearts of our children? If not, we as a church have a great deal of work to do.

Let us hope that many Catholic authors and illustrators (not to mention editors, jacket designers, layout designers, publicists and the rest of those whose skills are needed to make a picture book really sing) will continue the sort of work dePaola began, presenting the stories inspired by the Catholic faith to our children with all the richness—that is, all the truth, goodness and beauty—that it deserves.