In a previous column for America, I noted that the Beatitudes are about the needed internal growth of the Christian disciple to recognize the plight of the poor in spirit. Toward that end, the Beatitudes offer a training program to acquire a set of specific capabilities: empathy, meekness, an ascetical spirit, mercy, personal integration, reconciliation and a courageous self-offering. It is a transformational ladder of ascent, instructing us each to be like Christ by growing in virtues through devotional practices so as to attend to the poor in spirit.

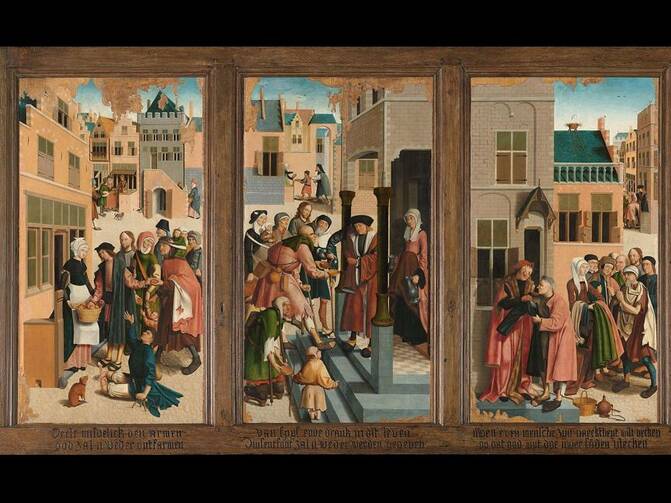

If the Beatitudes are for growing in vulnerability to the needs of others, then the works of mercy are the practices that Christian disciples collectively engage to respond to them, whether they are hungry, thirsty, sick, homeless, naked, imprisoned or even the abandoned dead who need to be buried. Both the Beatitudes and the works of mercy are our pathways, one inner, one outer, to lead us into fellowship with the poor in spirit.

Besides the Beatitudes, the works of mercy are intimately connected to the Eucharist. Indeed, shortly after the disciples left the Upper Room, they and their followers defined themselves as Christian by celebrating the Eucharist and the works of mercy. Following Jesus’ instruction to his disciples at the Last Supper to “do this in memory of me,” a phrase read in Luke (22.19), repeated in Paul (1 Cor 11.24-25), and reported in Acts (Acts 2: 42, 46; 20: 7-12) and Corinthians (1 Cor 11: 17-24; 16:1–2;) the disciples begin the practice of celebrating the Eucharist on Sunday, the day that Christ was raised.

Curiously, the disciples did not make Sunday a Christian Sabbath. Like Jesus, who broke the Sabbath ban on work, the early Christians seemed to be a busy lot, not resting in any noticeable way on the Sabbath or on Sunday. The general tendency of early Christians was to work seven days a week, including Sunday.

The famous Redemptorist historian of moral theology Louis Vereecke noted that the first texts of the early church positively exclude any cessation of work on Sunday. Paul shows no interest in the Sabbath, but instead highlights the importance of work (1 Thess 2: 9; 2 Thess 3: 10-12; Eph 4: 28). Following Ignatius of Antioch (d. 110), Ireneaus (d. end of second century) argues that Christians keep every day as their spiritual day, but no day as a day of repose. The Didascalia (third century) tells Christians that whenever they are not worshiping, they should dedicate themselves to work always and diligently.

As they developed the practice of receiving the mercy of God through the body and blood of Christ, the early Christians carried that mercy forward to others in exercising the works exhorted in the Gospel. I define mercy as the willingness to enter the chaos of another, which captures well, I think, how the Trinity began the work of our salvation by the Incarnation, through which Christ entered into our chaos to redeem us. Thus, we who receive that mercy practice it as well.

In Matthew 25, the saved are those who perform what we later called the corporal works of mercy—to feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, shelter the homeless, clothe the naked, visit the sick, visit the imprisoned and bury the dead. While the first six are found in Matthew 25, the seventh, to bury the dead, was added because the practice is so specifically Christian and pervasive.

The first work to emerge is tending to the sick. Indeed, just as Jesus began his ministry with many healings (Mk 1: 32–33; Mt 4: 23; Lk 4: 40–41), the disciples began theirs in much the same way: Shortly after delivering his remarkable Pentecost discourse in Acts 2, Peter heals the lame man at the start of Acts 3. By Acts 5: 12-15, we see that there have been so many healings by Peter that people bring their sick so that Peter’s simple shadow falls on them!

His miracles become even more astounding. In Lydda, Peter healed Aeneas, who was paralyzed for eight years (Acts 9: 32-35) and in Joppa, he even raises Dorcas from the dead (Acts 9: 36-40). But it is not only Peter tending to the sick. Ananias heals Paul of his blindness (Acts 9: 17-19). Paul, too, performs such miracles. He cures a man born lame at birth (Acts 14: 8-10) then later, like Peter, raises one from the dead, a Eutychus who falls to his death from a windowsill, apparently having dozed off while Paul is speaking.

These healings served as catalysts for later Christians to work collectively in attending to the sick by working together within their communities for greater health, and eventually moving to more institutional models of creating hospitals—as well as the specific leprosaria and the legendary “hospitals for the incurables.”

Another work of mercy that quickly became a Christian practice was visiting the prisoner. This corporal work has been practiced consistently throughout the life of the church. Christ himself had been a prisoner, like John the Baptist before him. Later Peter, Paul, James and many of the apostles are imprisoned as well. For Christians, prisoners were perceived as not only people in need, but also people of courage and holiness. Early church members visited their imprisoned brothers and sisters, worked to liberate them and sought their blessing as well. Clement of Rome (35-99 C.E.) wrote to Corinth in his Epistle that many ransomed others by offering themselves in exchange for the one held hostage. This Christian practice of visiting the prisoner perdured throughout history.

In the late 12th century and into the 13th century, charitable institutions were established for the release of prisoners. The Trinitarians (“Order of the Most Holy Trinity for the Redemption of the Captives”) founded by St. John of Matha (1160-1213), were singularly dedicated to ransoming prisoners and laboring to alleviate the conditions of those who remained in slavery. Similarly, The Royal, Celestial and Military Order of Our Lady of Mercy and the Redemption of the Captives was founded by St. Peter Nolasco (1189-1256) for the same task.

Often enough, prisoners were either debtors or those awaiting trial, sentencing or execution. In 16th-century Rome, for example, over half the imprisoned were debtors from the poorer classes; the others, awaiting trial, had not yet had their guilt established. The early Jesuits took care of the imprisoned by preaching, catechizing, hearing the confessions of the imprisoned and bringing them food and alms. Later they raised funds through begging to pay off the prisoners’ creditors. Elsewhere, they begged for money to ransom back prisoners taken by the Turks. Likewise, they preached against slave-taking raids and often they worked to improve the plight of prisons.

Later, another confraternity made up mostly of priests was dedicated to prisoners awaiting execution. They would visit the prisoners and spend the night with them before their execution, praying with them and helping them to identify with Jesus as a condemned prisoner. The following day, the priest dressed in white (hence known as the “Bianchi”) would accompany the prisoner to the gallows, walking ahead of him and holding a painted panel of the suffering Christ in front of his face so that the condemned man could keep his gaze fixed on Jesus instead of on the crowds or the executioners. Subsequently, the confraternity attended to the needs of the widows and orphans.

Later, in 1775 and 1777, Alphonsus Liguori, the patron saint of moral theologians, published a set of instructions, “Advice for Priests who Minister to those Condemned to Death,” noting that such men merited the “greatest sympathy” among any about to die, because of “four anxieties”: the fear of eternal punishment for their crimes; the dread of the execution itself, cutting short their lives; the public shaming of the execution itself; and the profound regret of leaving family, wives, parents and children without benefit of support and protection.

These confraternities helped their members to first recognize the prisoners and then their plight. From their experiences of the prisons, there grew subsequently numerous critical voices that protested prison conditions and started movements of reform to correct conditions among the imprisoned in Europe and elsewhere.

Perhaps the most interesting of the works of mercy is the last. While belief in the resurrection is, as Augustine notes, what separates Christians from others, the emperor Julian contended that one of the factors favoring the growth of Christianity was the great care Christians took in burying the dead. Though individuals often performed the task, the church as a community assigned it to the deacons, and, as Tertullian tells us, the expenses were assumed by the community. Lactantius reminds us further that not only did Christians bury the Christian dead, but they buried all of the abandoned:

We will not therefore allow the image and workmanship of God to lie as prey for beasts and birds, but we shall return it to the earth, whence it sprang: although we will fulfill this duty of kinsmen on an unknown man, humaneness will take over and fill the place of kinsmen who are lacking (Instit. 6.12).

Eusebius too reports that during the plague that raged during the reign of the emperor Maximus, Christians cared for the sick and buried the dead. The Christian community accompanied the dead to their resting place, and their care for the dead extended not only to burying them but also to making offerings for the repose of their souls.

Two insights are worthy of note here. First, we cannot underestimate how extensive this work was. For instance, though only five of the over 60 catacombs of Rome are open, visiting one gives a person a sense of the scope of this work. Therein, you see Christian reverence for the human body. It also helps us to understand that the catacombs were not secret hiding places. On the contrary, everyone knew, including the emperor, that Christians were burying the dead there. Moreover, and this leads to the second insight, they also went to the catacombs to be near their loved ones whose bodies were now with Christ in glory. They went there not to escape the Roman soldiers, but to be as close to another on earth who was already in glory.

While the early church has had a somewhat negative view on sexuality, it never, even by extension, had a negative view of the human body. On the contrary, as the works of mercy show us, early Christians tended to others’ needs for food, drink, housing, freedom and more because it would be in our bodies that we would one day meet our Risen Lord. Taking the human body and its needs seriously is what the church did as it taught the Beatitudes, practiced the works of mercy and celebrated the Eucharist in memory of Him.

More columns from James F. Keenan, S.J.:

“What the disciples learned while grieving in ‘The Upper Room’”

“The great religious failure: not recognizing a person in need”

“Vulnerability isn’t weakness. It’s what makes us human—and able to love.”