I went to the Met to take in the landscapes. I didn’t expect to find an old friend.

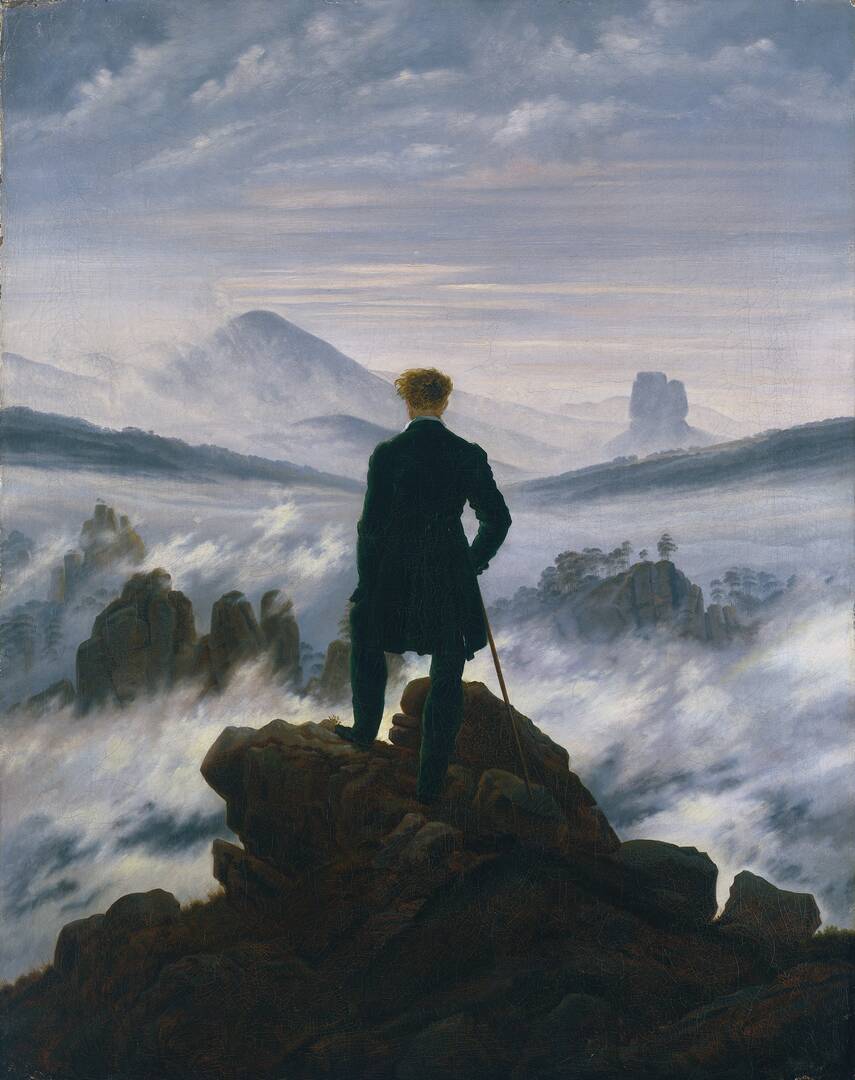

“Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature” arrived at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York this winter after a series of shows in Germany in 2024 marking the artist’s 250th birthday. You may not know his name, but it’s likely you know his most famous painting. “Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog,” the centerpiece of the exhibit, has been imitated numerous times, by artists like Anselm Kiefer and Kehinde Wiley, not to mention Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who used it to pitch the Green New Deal.

The painting, of a single, well-dressed hiker standing on a rocky ledge and gazing out over a foggy landscape, is a classic scene of man alone with nature. It’s the sort of work that puts you in mind of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, which was published 40 years after Friedrich composed his painting.

But the “Wanderer” can be a little misleading. Most of Friedrich’s work is not interested in a single human being alone in nature. Some of my favorites were of families or friends taking in the natural world around them. And those without people often featured religious imagery, like crucifixes on mountaintops. This is especially true of his early work.

Later in his career, he sought to evoke the “soul of nature” without any explicitly religious images. But God was there nonetheless. In his Summa Theologiae, Thomas Aquinas writes that God “produced many and diverse creatures, so that what was wanting to one in representation of the divine goodness might be supplied by another.” That is Friedrich in spades, capturing shards of divine beauty wherever he could find them.

I found that last quotation in “Renewing the Earth,” the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ pastoral letter on the environment from 1991. I read the document after visiting the Met because I had a hunch that it was ghostwritten by my friend and former boss at America, Drew Christiansen, S.J., who died in 2022. And it was Drew, even more than Thoreau or Aquinas, whom I was surprised to encounter amid the German landscapes on the Upper East Side.

Finding Solace

When I began working at America in 2006, Drew had been editor in chief for just over a year. He worked out of a large editorial office on the second floor of America House, which was then located on West 56th Street in Manhattan. I worked a floor above, in a small office that had once been a room in a hotel before the Jesuits acquired the building. Drew would often stop by my office to chat, and often our conversation turned to nature. When I told him I was going to the Catskills he recommended a trail in Claryville. Over the winters he advised me as I took up cross-country skiing.

Drew liked to take walks in Central Park to find solace. “The park has become for me, as for so many, a haven where I can breathe the light, smell the earth and listen to birdsong,” he wrote in one of his many Of Many Things columns. As a boy growing up in Staten Island, he would hike in the Adirondacks or the Catskills. Later, while studying and teaching in Berkeley, Calif., he would take long retreats in the mountains with his fellow students and other Jesuits. “In the summer, we would often camp and hike for a week at a time,” Drew wrote. “In the best years, it has meant three weeks outdoors for retreat and vacation.”

When I knew him, Drew did not have the same freedom to take weeklong retreats in nature because of age and some physical ailments. But that didn’t deter his enthusiasm for the natural world. At least once a year he recommended a nature scene for the cover of the magazine. One picture, of a cardinal sitting on a snowy tree branch in winter, provoked a lot of discussion among our readers. What was America saying about the hierarchy? Drew just liked the photograph.

When Drew died, 10 years after he left America for Georgetown University, my colleague Jim Keane wrote a lovely essay about his nature writing for the magazine: “The opening lines of his 2004 cover story for America, ‘Into the High Country,’ read like a cross between Tolstoy and Jack London: ‘The days were lengthening. Daylight itself seemed brighter. The sap was rising in the trees, and with it I felt the wanderlust rising in me.’”

Drew’s love for nature found its way into his work for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, where he helped build on the themes introduced in “Renewing the Earth.” Walter Grazer, who served as director of the environmental justice program for the U.S.C.C.B., spoke about the importance of that document at a forum at Georgetown University. “We have to remember that this pastoral was released at a time when the broader religious community, and certainly the Catholic Church with the exception of a few bishops’ conferences, had not yet placed concern for the environment on their agendas,” Mr. Glazer said. “In this sense it was a prophetic pastoral.”

Christ and the Landscape

Caspar David Friedrich arrives in New York at a time when the environment is on everyone’s agendas. (Well, almost everyone’s.) Nature as a fount of wisdom, spiritual or otherwise, has been conventional wisdom for some time now. So it’s interesting to note how Friedrich’s work was received in the 19th century.

One of the painter’s critics was his fellow German Basilius von Ramdohr, who took him to task for his painting “Cross in the Mountains,” which placed a crucifix in the background of a distant landscape. He saw it as a sign of disrespect for Christ. It would be “a veritable presumption, if landscape painting were to sneak into the church and creep onto the altar,” he wrote.

Such a sentiment seems antiquated today, of course. We all like to find God in nature: Just ask the pastor who has to explain why a Catholic marriage must be celebrated in a church rather than outdoors. But time has also perhaps made it more difficult to see God’s fingerprints in Friedrich’s paintings. A Christian imagination, for example, might look at the artist’s famous painting “A Monk by the Sea” and see a solitary man wrestling with the vastness of the world and God’s place in it. The exhibit’s catalog notes that Friedrich was “trying to express, through landscape, the conditions of belief itself: an experience of the ineffable.” Yet a critic today looks at it and sees nothing but a man alone in the universe. A critic for The New Yorker called it a “portrait of the most impossible thing in the world to represent: emptiness.”

In contrast, consider this quotation from John Updike, a Christian, who wrote about Friedrich for The New York Review of Books in 1991: “If Friedrich meant to imply Presence with his controlled, emptied vistas, and we can feel only absence, well, Absence is an old friend, and we wouldn’t know what to do with Presence if It came up and hit us in the face.”

What, then, does Presence look like? One can look, of course, to the religious images in Friedrich’s paintings. In addition to crucifixes, he painted the ruins of cathedrals in the German countryside. “Ruins of Oybin” (c. 1812) features a derelict Celestine monastery, which he encountered during a hiking trip. Friedrich’s practice was to sketch his scene on site, and then complete the final painting in his studio. In this case he added a crucifix, an altar and a sculpture of the Madonna and child to his final work.

Finding Presence in a landscape can be more difficult. But start by looking to the skies. “While light is the commonest metaphor for divinity,” Updike wrote in his essay, “Friedrich’s skies, which often take up more than half of his picture-space, show an especial tropism toward the realm of the glowing impalpable.”

For examples, see “Coastal Landscape in Morning Light” (c. 1817) or “The Evening Star” (c. 1830), both on view at the Met (the exhibit is open through May 11). The latter caught my eye because of the way it brings together nature and people. A boy, gesturing toward the evening sky, stands apart from his mother and, presumably, his sister. The Dresden skyline, marked by cathedral spires, can be seen in the distance. “The Evening Star” is Venus, but the planet is almost impossible to make out without the help of the painting’s accompanying text. Indeed, the boy is the star of this painting, at least for me; he, not the sky, is the subject of his mother’s gaze. He is with his family, but apart from them, and their distance foreshadows the day when he will leave home.

Triggers for Prayer

In his essay “Into the High Country,” Drew wrote that “the mountains hold natural triggers for prayer.” For Drew, it was flowing water or a field of wildflowers. For others, it was an encounter with animals. But friendship was also key. At the end of each day’s hike, Drew and his fellow backpackers would gather for Mass and spiritual conversation. At night they would sit by the fire and watch the stars. These were moments of “emotion recollected in tranquility,” to quote Wordsworth’s definition of poetry, but with another ingredient added to the mix: conversation.

Daniel Groody, C.S.C., vice president at the University of Notre Dame, accompanied Drew on some of these hikes as a graduate student. He remembers them fondly, especially the way the graces of the retreat would carry over into the months and years to follow. Drew sometimes could not complete a hike because of physical limitations, but those moments in nature “profoundly affected him,” Father Groody told me.

Drew was particularly inspired by the Jesuit paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin, who saw creation as imbued with the Spirit. “He often pointed me in that direction,” Father Groody recalled, “and it gave me a whole new way of understanding the sacramentality of creation.”

In “Two Men Contemplating the Moon” (c. 1825-30), Friedrich paints two men on a hillside looking at the moon in the distance. One man holds a walking stick, while the other rests his arm on his friend’s shoulder for support. The taller, older man is thought to be Friedrich himself, and the second his student, August Heinrich. Unlike in the “Wanderer,” these men do not face the world alone. They contemplate life’s beauty and its mysteries together. Is God present? It would depend, it seems, on the viewer. When Samuel Beckett saw the painting a century later, he was inspired to write “Waiting for Godot,” a play much more about Absence than Presence. But the evening star is there, once again, and the spring moon suggests nothing so much as the “glowing impalpable.”

In “Renewing the Earth,” the U.S. bishops tried to strike a balance. They worried that “twentieth-century Americans have..grown estranged from the natural scale and the rhythms of life on earth.” They invoked Scripture (“Mountains and hills, bless the Lord…”) and the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins to turn our hearts toward the goodness of the natural world. That call has been heard, most notably by Pope Francis.

But while God can be found in nature, the bishops noted, nature is not itself God. It can only offer glimpses of God. What’s more, nature cannot be seen apart from the humans who inhabit—to use a more recent phrase—“our common home.” “A distinctively Catholic contribution to contemporary environmental awareness,” the bishops write, “arises from our understanding of human beings as part of nature, although not limited to it.”

It is this mix, of people immersed in nature but also finding time to care for one another, that I found most compelling in the work of Caspar David Friedrich, and which reminded me of my friend Drew. So go to the Met, or pick up the catalog, and revisit the bishops’ pastoral letter from 1991. It ends with a prayer I remember well from my early days at America, for Drew recited it at the beginning of every meeting:

Send forth thy Spirit, Lord

and renew the face of the earth.