Editor's note: This article originally appeared in America on March 28. 2005.

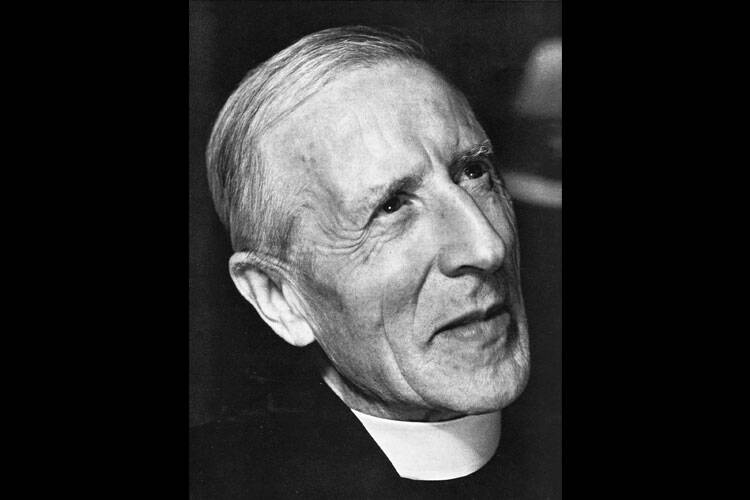

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., died 50 years ago in New York City. At the time, he was widely recognized in U.S. scientific circles for his work on the geology of Asia and his studies of Peking Man. Otherwise, he was virtually unknown. He had written abundantly in philosophy and theology, but church officials had prevented publication, although some of his essays were widely circulated during his lifetime in manuscript form. After his death, friends in Paris did what he had not been permitted to do; they published 13 volumes of his religious writings. By the time the Second Vatican Council began, less than a decade later in 1962, Teilhard had come to be regarded as a saint for the times. But his sanctity was unusual; it showed itself chiefly in a dedication to the world and secular work.

During World War I, Teilhard was a stretcher-bearer in the French Army and much respected by his fellow soldiers for his indifference to danger. After the war, he returned to the University of Paris to complete his doctoral studies in geology. He approached science as a “religious devotee” and spoke of a “sacred duty of research. We must test every barrier, try every path, plumb every abyss.” To Teilhard, research was a form of adoration, involving its own asceticism. His work took him through blistering heat and icy blizzards, snakes and scorpions, bad food and no food, political instability and exile. Through it all, Teilhard came to be known as “the smiling scientist.” A young Chinese geologist found it “a moving experience to see how much the man could bear.”

Teilhard was striving for sanctity by working in science, and this effort would require a new understanding of what it means to be holy.

Teilhard was striving for sanctity by working in science, and this effort would require a new understanding of what it means to be holy. The traditional understanding of sanctity regarded secular work as a “spiritual encumbrance” and viewed “the world around us as vanity and ashes.” To come to the things of God required rejection of the things of earth. So says the First Letter of John: “Do not love the world or the things of the world” (2:15). Likewise, St. John of the Cross: “Desire to enter into complete detachment, emptiness, and poverty with respect to everything that is in the world.” Worldly knowledge and secular concerns were thought to lead to pride. “Study to withdraw the love of thy soul from things that be visible, and turn it to things that be invisible,” wrote Thomas à Kempis.

As the 20th century advanced, seminaries still recommended such texts, but most Christians no longer found in them the expression of a human ideal. Nonetheless, when Teilhard’s Divine Milieu was finally published in 1958, the dedication came as a shock: “For those who love the world.”

In 1916, in the lulls between battles, Teilhard wrote the first of the essays that would make him famous, “Cosmic Life.” In it he described a communion with earth as a way of attaining communion with God. His theology centered on the Pauline idea of the “body of Christ.” Christians were called on by Paul to see themselves not as separate individuals but as one body. Furthermore, St. Paul’s writing suggested to Teilhard that the “body of Christ” might include the material world, for Christ was progressively uniting all things to become the one in whom “all things hold together” (Col 1:17). Such a unity could be achieved only by building a secular infrastructure. Through work in science, technology, government, education and the unity of peoples, Christians were called to develop the world so that it might be a suitable body for Christ, who would be its soul. Evolution was a building process, and Christians should commit themselves to continue it. “Collaboration in the development of the cosmos,” he wrote, “holds an essential and prime position among the duties of the Christian.” Teilhard suggested that there ought to be a religious community in which people would vow themselves to further the work of the world, a work that would have its own asceticism in its denial of “egotism” and would call for a “supreme renunciation.”

Teilhard's sanctity was unusual; it showed itself chiefly in a dedication to the world and secular work.

It was a new way of thinking. Christians could love the world—for Christ was found there. Suffering was no longer a penalty for sin, but the price each of us must pay to bring the universe to its completion in Christ. Several weeks after completing “Cosmic Life,” Teilhard added a postscript acknowledging that he had introduced “a completely new orientation into Christian ascetical teaching.” Pierre Leroy, Teilhard’s closest Jesuit friend in his final years, tells an anecdote that shows how lay Catholics were particularly taken by his words. When a successful businessman asked for clarification, Teilhard responded:

Since everything in the world follows the road to unification, the spiritual success of the universe is bound up with the correct functioning of every zone of that universe, and particularly with the release of every possible energy in it. Because your enterprise... is going well, a little more health is being spread in the human mass, and in consequence a little more liberty to act, to think, and to love.

As World War I dragged on, Teilhard developed his ideas in additional essays. But when he sent several to his religious superiors, some of them were disturbed. They feared that in his emphasis on God’s presence in the world, he was verging on pantheism. He even seemed to accept the term. To defend himself, Teilhard again appealed to St. Paul, who spoke of Christ as head over all things and Christ’s body as “the fullness of him who fills all in all” (Eph 1:23).

When Teilhard returned to civilian life, he sought confirmation of his “new orientation” by sending essays to Maurice Blondel, a noted philosopher and prominent Catholic scholar of the time. In an accompanying letter Teilhard argued that a spirituality of renunciation was not viable for humanity as a whole. Most people must work long hours in the secular world, he pointed out, and these hours should not be apart from a communion with Christ. In his response, Blondel expressed his own concern that some of Teilhard’s passages verged on pantheism. But he also found something very right in Teilhard’s message. Blondel had come to a similar spiritual understanding himself but hesitated to voice it publicly. He was “held back, troubled for long periods by all the testimonies and authorities who advised against it,” for Catholic scholars generally regarded worldly concerns as “vanity, affliction of the spirit, perversion of the heart.” Reading Teilhard, Blondel was encouraged: “How much confidence and reassurance it has given me!”

In his exchanges with Blondel, Teilhard developed a second phase in his spirituality. First, one must love the world. Then, when the time comes, one must renounce it. With a spirituality of growth and self-development, “one is only half-way along the road that leads to the Mount of Transfiguration.” One also needs a spirituality of diminishment, surrender and death. Teilhard speaks of our “annihilation” (a term he picked up from St. John of the Cross)—the time in every life when the current of events goes against us, and we find ourselves beaten by the forces of this world. We face our limitations, failures, suffering and death. For Teilhard, these too could bring God to us and us to God. “If we believe,” he wrote, “the power with which we clash so agonizingly ceases to be a blind or evil energy. Hostile matter vanishes. And in its place, we find the divine Master.”

Still, before annihilation, humans must first develop themselves and in so doing develop the world. “The universal striving of this world can be regarded as the preparation for a sacrifice that will be offered.” Like climbing a ladder, we must first hold onto the step and then let it go. Human love is our initiation to love and a preparation of the heart for divine love.

Christians concerned with the environment, like Thomas Berry, Al Fritsch, S.J., John Grim and Mary Evelyn Tucker, have also looked to Teilhard for inspiration.

Teilhard, therefore, did not disagree with the spirituality of renunciation, but felt that it was not the right place to begin. Success is not the whole story, nor is failure. But Jesus is found in pain and loss only after we have tried our best to find him in a work that is good.

In 1923, while excavating in canyons close to the Great Wall of China, Teilhard wrote what is probably his most popular essay, “The Mass on the World.” Standing on the yellow soil of China, he told of making the entire earth his altar. At the offertory of this Mass, he offers all the labors and sufferings of the world. The bread includes all that springs up, grows, flowers and ripens; the wine all that corrodes, withers and is cut down. In the consecration, Christ speaks through the priest to claim the world’s growth as his body and its anguish and death as his blood. Christ is everywhere, and the world is consecrated as his flesh.

Following the wonder of the consecration, the priest proceeds to Communion. Reaching for the “fiery bread,” he makes a commitment to moving beyond himself and being drawn into labors, dangers and a constant renewal of ideas. Through all of these he will grow and in the process find God: “The man who is filled with an impassioned love for Jesus hidden in the forces which bring increase to the earth, him the earth will lift up, like a mother...and enable him to contemplate the face of God.”

But ultimately the kingdom of God is not of this world. The God immanent to the world is also radically transcendent. Hence one cannot enter into God simply by working for an earthly cause, no matter how great. For a final union, one must pass through agonizing diminution and death, for which no tangible compensation is given. “That is why, pouring into my chalice the bitterness of all separation, of all limitations, of all sterile fallings away, you then hold it out to me, ‘Drink ye all of this.’” Jesus is hidden in these forces, and those who love him there eventually “will awaken in the bosom of God.” Teilhard quotes an unnamed Jesuit of the 16th century: “You, Lord, lock me up in the deepest depth of your heart; and then hold me there, burn me, purify me, set me on fire, sublimate me, till I become totally what you would have me be through my utter annihilation.”

Many modern theologians and spiritual writers consider themselves indebted to Teilhard as well.

In the half-century that has passed since Teilhard’s death, the church has experienced many changes. Most are associated with the Second Vatican Council, where many see Teilhard’s influence at work. The council’s “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World” (1965) reaches out to the secular world by stressing the value of the secular and the wonders of technology. It sees scientists working “with a humble and steady mind,” being led by the hand of God and Christ as Omega, “the goal of human history.” Individuals and nations are called upon to join together to become “artisans of a new humanity.” Human development is a common responsibility—a thought Teilhard had expressed in his first essay. Bishop Otto Spülbeck of Meissen, Germany, reported that Teilhard’s name was mentioned four times as the bishops in the council’s main assembly hall were working on the text of the conciliar document.

Many modern theologians and spiritual writers consider themselves indebted to Teilhard as well. Jon Sobrino, S.J., has credited Teilhard with influencing his work on liberation theology. Christians concerned with the environment, like Thomas Berry, Al Fritsch, S.J., John Grim and Mary Evelyn Tucker, have also looked to Teilhard for inspiration. Michael Comdessus, director of the International Monetary Fund for 14 years, said he thought of Teilhard in his work every day. Even spiritualities with little connection to Christianity have drawn from him. When Marilyn Ferguson, author of The Aquarian Conspiracy, asked 185 New Age leaders who had the greatest influence on their thinking, Teilhard was mentioned more than anyone else.

All of these are among “those who love the world.” Teilhard would have been encouraged. He tells of praying his “Mass on the World” many times. It reminded him that there are two forms of Communion: in our growth we communicate with Christ’s body, and in diminishment and death we communicate with his blood. Looking ahead to his own death, Teilhard noted that all the faithful want to receive Communion as they die. He asked for something more: “Teach me to treat my death as an act of Communion.” On April 10, 1955—Easter Sunday—Teilhard suffered a fatal heart attack, and his Communion was complete.

The Smiling Scientist

Muslim troops from Algeria spoke of Teilhard as sidi, a term of religious respect. A fellow soldier observed:

The North African sharpshooters of his regiment thought he was protected by his baraka [Arabic for “supernatural bearing”]. The curtain of machine gun fire and the hail of bombardments both seemed to pass him by.... I once asked, “What do you do to keep this sense of calm during the battle? It looks as if you do not see the danger and that fear does not touch you.” He answered, with that serious but friendly smile that gave such a human warmth to his words, “If I am killed, I shall just change my state, that’s all.”

—Michael Conte, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1968)