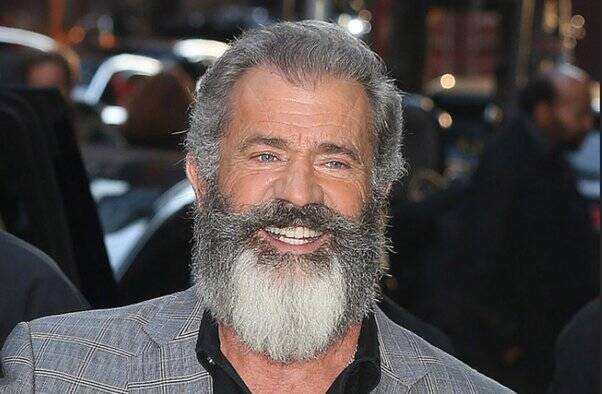

Actor and director Mel Gibson was in the news this week when rumors surfaced that filming will begin this spring on a sequel to his 2004 film “The Passion of the Christ.” That film, which he self-produced, grossed over $600 million worldwide. It is the highest-grossing independent film of all time.

It was not Mr. Gibson’s only appearance in the news this week, however: On Jan. 9, the Krewe of Endymion, which hosts one of the three largest Mardi Gras parades in New Orleans, rescinded their invitation for him to be their co-grand marshal hours after announcing it. The Krewe explained that their announcement had been met with immediate widespread negative feedback, including threats, and they made their decision out of a concern for the safety of all involved.

The Endymion story is the latest in a long series of ugly moments surrounding Gibson, stemming from antisemitic comments that he has made both publicly and reportedly in private over many years. And Endymion’s decision to choose to honor him brings up important questions about forgiveness and responsibility.

The Endymion story is the latest in a long series of ugly moments surrounding Gibson, stemming from antisemitic comments that he has made over many years.

Like father, like son

In a sense, Mel Gibson’s problems begin with his father Hutton, a “Jeopardy!” grand champion from Peekskill, N.Y., who moved with his wife and 10 children to Ireland and then Australia in 1968 after a work-related injury.

Hutton Gibson was a devout Catholic but a fierce opponent of everything to do with the Second Vatican Council, going so far as to label every pope from John XXIII onward a heretical “anti-pope.” Gibson was also rabidly antisemitic. In an interview in 2004, he denied that the Holocaust ever happened, saying the Nazis “knew how to do things, and if they had set out to kill six million Jews, they would have done it. But all we hear about is Holocaust survivors.” A year before, he had told The New York Times Magazine that Vatican II was “a Masonic plot, backed by the Jews.”

Like his father, Mel Gibson rejects the modern Catholic Church and considers himself a sedevacantist Catholic [literally, “The Holy See is vacant”]. “There was nothing wrong with the Catholic Church before Vatican II’s reforms,” Gibson, who was 6 when Vatican II began, said on a press tour for the film “Father Stu” last year. “It didn’t need to be fixed. It was doing pretty well.” Gibson built his own church in the Agoura Hills (not far from Malibu), the Church of the Holy Family, which holds services but has no relationship with the Catholic Church.

Gibson’s history is also marked by a series of antisemitic statements similar to those of his father. In 2013, he did an interview with Republican speechwriter Peggy Noonan for Reader’s Digest. Outtakes from that interview that were later released saw him casting doubt about the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust: “When the war was over they said it was 12 million. Then it was six. Now it’s four. I mean, it’s that kind of numbers game.”

Unlike his father, Gibson acknowledged that the Holocaust happened. But he argued that it was just one loss of life among others. “The Second World War killed tens of millions of people. Some of them were Jews in concentration camps,” he told Noonan. “In the Ukraine, several million starved to death between 1932 and 1933. During the last century, 20 million people died in the Soviet Union.”

Others have described Gibson kidding about the Holocaust privately. Actress Winona Ryder tells the story of Gibson coming up to her at a party in the 1990s and asking her whether she was an “oven dodger.” (He also looked at her friend, who was gay, and asked, “Oh wait, am I gonna get AIDS?”)

Screenwriter Joe Eszterhas, who worked with Gibson on a film version of the biblical Book of Maccabees, wrote a letter to Gibson in 2012 after the project was canceled, enumerating the many antisemitic things that Gibson had said during their work together: his use of words like “Hebes,” “oven-dodgers” and “Jewboys” to refer to Jewish people; calling the Holocaust “mostly a lot of horseshit” and insisting that the Torah “made reference to the sacrifice of Christian babies and infants,” a claim made in the antisemitic "Protocols of the Elders of Zion."

“You told me the mothers of the last three Popes of the Catholic Church were Jewish, and you said there was a Jewish/Masonic conspiracy to destroy the Catholic church,” Mr. Eszterhas wrote.

Actress Winona Ryder tells the story of Gibson coming up to her at a party in the 1990s and asking her whether she was an “oven dodger.”

‘The Passion of the Christ’

In 2004 Gibson released his film “The Passion of the Christ,” which he said was meant to “tell the truth” about the death of Jesus of Nazareth. Prior to the film’s release, the head of a scholarly group convened by the Jewish Anti-Defamation League and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a statement saying his group found the script to be “one of the most troublesome texts related to antisemitic potential that any of us had seen in 25 years.”

Gibson’s sources for the film included the writings of two nuns whose writings were filled with antisemitic tropes. One of them, Sr. Anne Catherine Emmerich, “was an early 19th century German stigmatic who often described Jews as having hooked noses,” Rabbi Marvin Heir and Harold Brackman of the Simon Wiesenthal Center wrote in The Los Angeles Times. She “told of a vision she had in which she rescued from purgatory an old Jewish woman who confessed to her that Jews strangled Christian children and used their blood in the observance of their rituals.” This claim had been used to stoke violence against the Jews throughout their history, including by the Nazis.

After the film came out, the Anti-Defamation League wrote: “We fear the consequences of this film. There will be many people who are not so familiar with the Gospel narratives and might believe that everything they see on the film derives directly from the New Testament.

“We are also concerned about those who already are disposed unfavorably toward Jews and will use this to fan the flames of hatred,” they said. And that is exactly what happened; NBC News reported on Arab people who saw the film and believed it “unmasked the Jews’ lies.” And in the United States, after four years in which hate crimes against Jewish people had gone down or stayed the same, attacks increased.

Before the film’s release, A.D.L. National Director Abraham H. Foxman asked Gibson to include a card at the end that would “implore your viewers to not let the movie turn some toward a passion of hatred.” Gibson replied only that he hoped the A.D.L. and he would “set an example” of showing “love for each other despite our differences." (Some critics disputed the charge of antisemitism.)

Incidents of antisemitism in the United States have gone up 34 percent just in the last year, to an average of more than seven a day.

The arrest

Two years after “The Passion of the Christ” came out, Gibson was pulled over by an L.A. County sheriff’s deputy on suspicion of driving under the influence. Gibson became belligerent toward the officer and made a series of antisemitic remarks, including “The Jews are responsible for all the wars in the world.” Then he asked the officer if he was a Jew.

Gibson issued a statement through his publicist the day after the incident, saying: “I acted like a person completely out of control when I was arrested, and said things that I do not believe to be true and which are despicable. I am deeply ashamed of everything I said, and I apologize to anyone I may have offended.”

But since then, Gibson has mostly minimized the incident, calling it simply “unfortunate” in 2016 and complaining that he was the one victimized. “I was recorded illegally by an unscrupulous police officer who was never prosecuted for that crime,” he told Variety. “And then it was made public by him for profit, and by members of—we’ll call it the press. So, not fair.”

In fact, as reported by Forward in 2020, that officer—who indeed was Jewish—had been pressured by his supervisors “to remove the antisemitic remarks from Gibson’s incident report” after it happened. He refused, and soon after began to be passed over for promotions. After he sued the department and won a settlement, they fired him, forcing him to sue again to get his job back.

Redemption is not earned by waiting out the impact of one’s mistakes, it is earned by actually doing the work of repair.

Why is this still an issue?

In that same interview with Variety, Gibson argued, “I don’t understand why after 10 years it’s any kind of issue.”

“For one episode in the back of a police car on eight double tequilas,” he said, “to sort of dictate all the work, life’s work and beliefs and everything else that I have and maintain for my life is really unfair.”

But it’s not just one episode. And meanwhile, incidents of antisemitism in the United States have gone up 34 percent just in the last year, to an average of more than seven a day. “This is the highest number recorded since 1979,” the Anti-Defamation League in New Orleans wrote in response to the Endymion invitation, “when ADL began tracking such incidents.”

An A.D.L. report on antisemitic attitudes in the United States released Thursday likewise found that “over three-quarters of Americans (85 percent) believe at least one anti-Jewish trope,” a jump of a massive 24 percent in less than four years. Matt Williams, vice president of the A.D.L.’s Center for Antisemitism Research, told The Washington Post that American attitudes are more and more reflecting “antisemitism in its classical form…where Jews are too secretive and powerful, working against interests of others.”

To invite someone who has repeatedly made antisemitic remarks to have a highly public role in a major city function (and an ostensibly Catholic one at that) serves to normalize that behavior. It sends the message that those attitudes are either no big deal or legitimate.

And in saying that it rescinded its invitation out of safety concerns, Endymion—whose recent history includes passing out blackface figurines—seems intended to stir up more hostility toward Jewish people. As the A.D.L. officials wrote, “Blaming the public for their reaction to the krewe’s misguided choice is an affront to the residents of New Orleans, and all who stand against bigotry and hatred.”

For years now, Gibson has been saying it is time that people forgive him, that holding him accountable for comments from a decade or more ago is ridiculous and unfair. No doubt some Catholics and others feel the same at this point. They think he’s “done his time.”

But redemption is not earned by waiting out the impact of one’s mistakes, it is earned by actually doing the work of repair. Gibson hasn’t done that yet. Meanwhile, Jewish people in the United States find themselves more and more misunderstood and mistreated. In that climate, holding Gibson up as a leader is not only wrong, it’s dangerous.