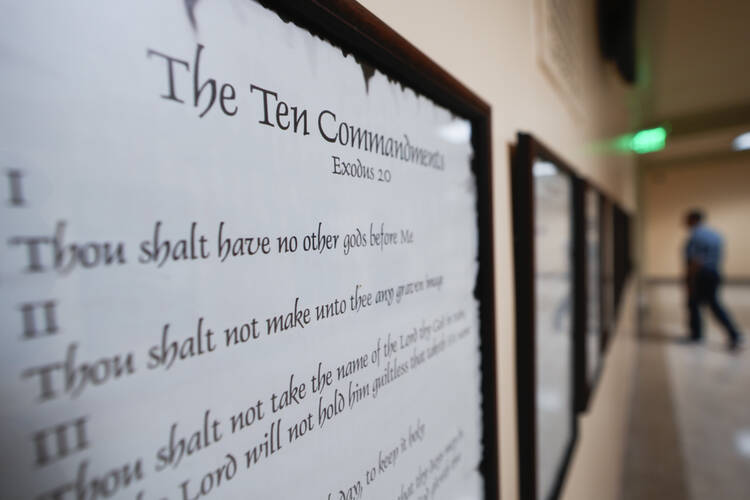

On June 19, Louisiana’s Republican governor Jeff Landry signed a law ordering that the Ten Commandments be displayed in every public school classroom in the state. Critics have assailed this move as an attack on the separation of church and state, but proponents have retorted that such a separation is unconstitutional, hostile to religion and should be done away with.

In the wake of the law’s passage, I spoke with Jacques Berlinerblau, a professor of Jewish Civilization at Georgetown University, who has written numerous scholarly books and articles on the subject of secularism, including the forthcoming second edition of Secularism: The Basics (Routledge).

This interview was conducted by email and has been edited for clarity and length.

Connor Hartigan: As a scholar of political secularism, how would you define that term?

Jacques Berlinerblau: Let’s start with what secularism is not because confusion runs rampant in discussions of this term, and the Louisiana case is no exception. Secularism is not atheism. The latter is an approach centered around the materialist conviction that there is no god or gods. Nor is it accurate to assume that secularism is synonymous with the oft-cited notion of “separation of church and state.” It’s also inaccurate to say that secularism is the “opposite” of religion. The opposite of secularism is fundamentalist religion. What we are seeing in Louisiana is a classic fundamentalist conceit. Namely, “thou shalt be subject to my religious views!”

Then what is secularism?

I think of the term as referring to a philosophy about the proper role and function of the state vis-à-vis religious citizens. (In my work, I have traced a very Catholic genealogy of political secularism, one that runs from the Gospels to St. Augustine, to Marsilius of Padua, to William of Ockham and beyond). A “secular” state is one that seeks to regulate the relationship between itself and religious citizens and among religious citizens themselves. It does so while bound to the precept that the state has no preferred or established religion. The secular state thus remains neutral with respect to all religious groups and non-religious groups.

What about secularism might be offensive to some religious citizens?

This brings us to another core aspect of political secularism. Put bluntly, the state is “on top.” In other words, in a disagreement with citizens of faith—which the ideal secular state always tries to avoid—it is the state that prevails. Historically, certain religious formations have taken umbrage at being placed in a position of subordination to the state.

Let’s apply your definition to the current situation in Louisiana. What would a secularist say about Governor Landry’s initiative?

Louisiana is not, according to our definition, a secular state because it has violated the principle of neutrality and veered dangerously close to endorsing what some might call Christianity—but I would call a particular form of Protestantism—as the official religion of the state.

What do you mean by “a particular form of Protestantism”?

Governor Landry is advocating a preference for those Protestant forms of Christianity that: 1) abide by the particular translation and numbering of the Decalogue that will be displayed in classrooms and 2) fervently believe that their religious views should be shared with all public school students in Louisiana. So the state of Louisiana is “on top,” but it’s certainly not a secular state.

Governor Landry is himself Catholic. What do you think explains a Catholic governor’s willingness to advance a Protestant religious vision in the public square?

This union of some Catholics with evangelical and fundamentalist Protestants—what they refer to as “co-belligerency”—is one of the defining stories in American politics over the last half-century. As I see it, the narrative commences in the 1960s and 1970s. It features a historically unprecedented but devastatingly effective political alliance between evangelical and fundamentalist Protestants on the one side and Catholics concerned by the reforms of the Second Vatican Council on the other.

These groups put aside nearly half a millennium of intense theological antagonism. Catholics, for their part, willingly forgot several centuries of discrimination that they endured in the United States at the hands of their newfound allies. For these Catholics, the predominant issue was Roe v. Wade and to a lesser degree the liberalizing cultural drift of the 1960s. In my own writings, I’ve noted that the Catholic contingent—although much smaller—was and has always been the brains of the enterprise. They were the leading strategists, legal theorists and intellectual first responders.

Do you think Governor Landry is wrong about political secularism in relation to American Catholics’ interests? Why should American Catholics support political secularism?

If there’s one thing I’ve learned after decades of studying secularism, it’s that religious minorities generally benefit from, and support, secular states. Catholics in the United States are a minority, one not unfamiliar with religious discrimination. And those old Catholic-Protestant antagonisms I alluded to above are not fully erased. Nary a week goes by without a Protestant co-belligerent making some hair-raising claim about the Catholic faith. Once secularism is vanquished, what safeguards do Catholics have against the possibility of rule by a religious majority?

Here’s an example: In a post-secular country, what would prevent South Carolina or Oklahoma or Louisiana’s legislature from enacting an establishment of some form of Protestant religion? And what happens to Catholics under this new dispensation? What if a Protestant governor decided not only to mandate Protestant prayer and the display of a Protestant Decalogue in schools but to forbid Catholic students from wearing crucifixes or carrying rosary beads?

What else do we know about Catholics’ history with political secularism?

It’s essential to recall that religious believers’ relationship with secularism is usually situational; it depends on their relationship to the dominant religion in a given polity. There have been times and places where Catholicism has abhorred political secularism. One thinks of Pius IX’s “Syllabus of Errors,” and the Vatican's opposition to political secularism in Mexico and France during the 19th century. But there have been times when individual Catholics and even national Catholic communities have been at peace with secularism.

Why is that?

Usually that was because Catholics were in the minority; they were afraid of what a religious majority with the full power of that state at its disposal might do to their religious freedom. Here we could speak of Senegal, Eritrea or, again, the United States during the mid-20th century. Let’s recall John F. Kennedy declaring in 1960 that “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute.” He was articulating not only the core principle of separationist secularism and of fair play but also a principle that served to protect the rights of the American Catholic community.

On the flip side, what reasons might American Catholics have to be suspicious of political secularism?

They do have reasons. During the 19th century, nativist, xenophobic Protestants (for instance, the Know-Nothing Party) advocated “separation of church and state” in an extremely cynical ploy to deprive Catholics of equal rights in the public sphere. Separation of church and state, which I noted above is not a synonym for secularism, was paradoxically used as the justification to permit Protestant-inflected prayer and Bible-reading in schools and keep Catholic forms out. That Protestant version of separationism, however, was deeply flawed and few secularists today would associate themselves with it.

Many proponents of Governor Landry’s initiative in Louisiana appeal to the notion of religious freedom as well. Shouldn’t Louisianans have the liberty to promote their religious tenets, even in the classroom?

In principle, yes. But whose religious freedom are we talking about? Much is made in Republican circles about parents’ rights, but what about the rights of Sikh or Hindu parents whose children have to stare at the Ten Commandments all year in homeroom? Or what about a Catholic kid looking at a Protestant translation and numbering of the Decalogue? (If that seems far-fetched then read about the role of Bible translations and mass violence in the so-called “Bible Wars” of mid-19th century America.) So, yes, religious believers have a majority stake in political secularism.

If you could tell all American Catholics one thing about political secularism, what would it be?

Although I am not a Catholic, I teach at a Jesuit institution, and my experiences there leave me hopeful that both the laity and the church will do the right thing. This is not only because political secularism protects the religious freedom of Catholics domestically and globally. There’s a more catholic reason, so to speak, for a Catholic preference for secularism. Political secularism accords equal rights to all human beings created in the image and likeness of God. I have faith—secular faith—that Catholicism will recognize the sanctity of that concept.