Timely counsel from America’s first commander in chief

Insightful, engaging and suddenly very timely—how’s that for a letter written to a newspaper in 1796?

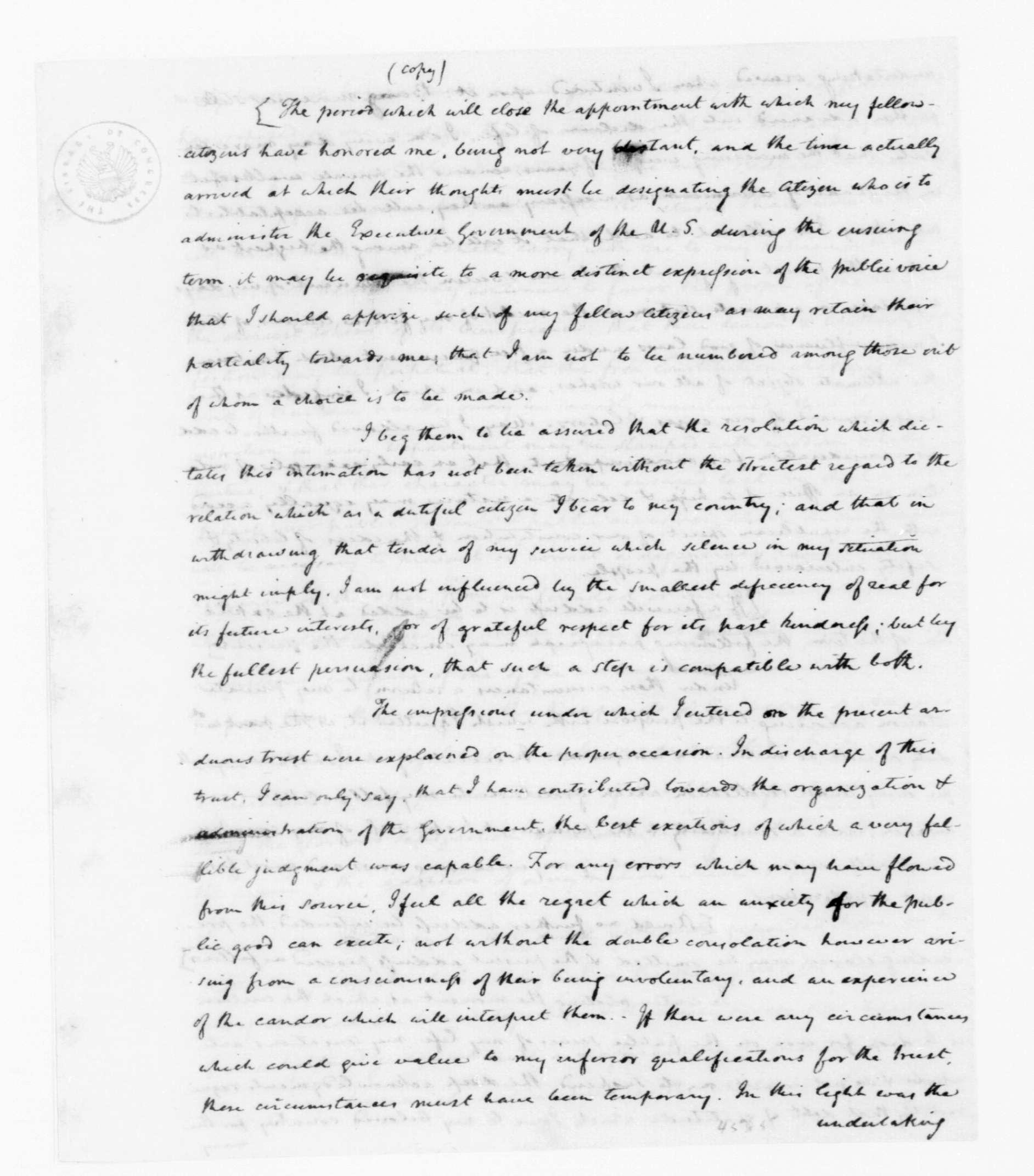

Now known simply as Washington’s Farewell Address, this public notice to “Friends and Fellow Citizens” was the way the country’s founding president announced that he would not seek a third term. It was also the way he shared his hopes and fears for the young country’s perilous future.

George Washington had appeared in person to address the Congress in 1783 when resigning his commission as commander in Chief of the Continental Army. But this 1796 farewell was written, not spoken—although it is still read aloud in the U.S. Senate on Washington’s birthday. The author of this book, John Avlon, editor in chief of The Daily Beast and a political analyst for CNN, calls it “the most famous American speech you’ve never read.” His perceptive view of American history and his agile prose make a convincing case for why you should read Washington’s farewell today.

Voted unanimously by the Electoral College to two terms as president, George Washington personified the new nation. He had wished to serve but one term and began drafting a farewell address in 1792. By then, however, Washington found himself to be a needed conciliator among hostile “factions” within his own cabinet, and it was only the specter of a civil war without his steady leadership that prompted him to stay on.

Washington knew from the start just how fragile the new republic would be. He was president of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, where he dealt first-hand with the conflicts inherent in forging this novel political system. He strove then to reconcile tensions that still persist: between federal and state governments, between urban and rural communities, and between an industrial North and an agrarian South. The only president to be a true independent, before the rise of political parties, Washington still had to endure divisive partisan strife between those later called the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans.

During Washington’s second term, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton was a loyal aide, but Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the principal drafter of the Constitution, secretly founded The National Gazette as a paper that ceaselessly attacked Washington.

When in 1793 Washington declared U.S. neutrality between the warring French and British, he was denounced for abandoning an ally. France reacted by sending as its ambassador Edmond-Charles Genet, whose secret mission was to foment a popular revolt against the president. And when in 1795 the Chief Justice of the United States John Jay negotiated a treaty with Britain as a way to buy time for the fledgling nation to recover from war and expand trade, it was attacked for aiding a former enemy. Washington couldn’t wait to return to Mount Vernon.

Yet Washington’s Farewell became more than his personal view of America’s future because by enlisting Madison, Hamilton and Jay—all three authors of The Federalist Papers that had advocated ratifying the Constitution—he drew on diverse perspectives from his fellow founders. Washington asked Madison to try a first draft in 1792, used Hamilton as his principal ghostwriter in 1796 and enlisted Jay to edit the many drafts as they evolved.

Avlon eloquently highlights six themes or “pillars of liberty” celebrated by the address: national unity, political moderation, fiscal discipline, virtue and religion, education, and foreign policy. He calls the address’s history and drafting “an autobiography of ideas,” and in this telling Washington comes alive as a prophet of today’s political ills. Partisanship, he warned, “agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection” and “opens the door to foreign influence and corruption.” Washington was a practical advocate of enlightened citizenship, and his “overriding focus was turning the fact of independence into enduring liberty,” Avlon explains. “This is not an incidental distinction: While freedom can be a state of nature, liberty requires a degree of self-discipline. It is the essence of self-governance.”

A man with little formal schooling himself, Washington valued public education both to endow his fellow citizens with practical skills that would enrich the country and to assure that “public opinion should be enlightened.” Washington also advocated religious pluralism and spurned the “horrors of spiritual tyranny and every species of religious persecution.” His own strong sense of personal morality and decorum he developed by reading a 17th-century Jesuit guide known as “Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.”

While the address is remembered for warning against “entangling alliances,” the phrase itself was actually first used by Jefferson at his first inauguration. Washington’s counsel is timeless nonetheless and could well apply to the way the United States treats Iran and Russia today, just as it did to France and England in his time: “The nation which indulges towards another a habitual hatred or a habitual fondness is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest.”

Through later generations the address was quoted by Jackson to oppose secession and by Lincoln to forestall civil war, although Jefferson Davis also used it to celebrate the Confederacy’s “constitutional liberty.” Lyndon Johnson cited its call for public education, and Gerald Ford commended its principles of religion and morality. Unfortunately, the address was also badly misconstrued, as in 1939 when the German American Bund rallied in Madison Square Garden, claimed that it justified U.S. neutrality toward Hitler and circulated a pamphlet titled “George Washington: The First Nazi.”

Mostly, however, Washington’s Farewell Address has survived as civic scripture, memorized by school children and celebrated in government and commercial advertising. In 2015, the sell-out Broadway musical “Hamilton” set key phrases from the address to hip-hop song and verse that celebrated the peaceful transition of power and the bond of citizenship.

Dwight Eisenhower said that as a young man he “idolized” Washington, and as retired general himself he echoed the address’s warning against “overgrown military establishments” in 1961, when he delivered his own farewell on national television. Then he condemned the “military-industrial complex” as a threat to “our liberties” and “democratic processes.” It is notable that Three Days in January, a book by Bret Baier and Catherine Whitney about Ike’s farewell, has also recently appeared.

Washington’s Farewell complements another fine book about presidential rhetoric, Lincoln at Gettysburg, by Garry Wills. The two volumes focus on different values from the country’s anxious founding days. Wills shows how in just 272 words Lincoln drew on the Declaration of Independence to rededicate a fractured nation, while Avlon parses the 6,088 words Washington shared to celebrate the principles and the powers inherent in the Constitution.

Avlon gives us a vivid and engaging review of Washington’s decisive role in shaping our history: first as a general when helping to gain American independence, then as a scribe whose farewell guides his fellow citizens on a courageous quest that remains unfinished to this day.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Timely counsel from America’s first commander in chief,” in the April 3, 2017, issue.