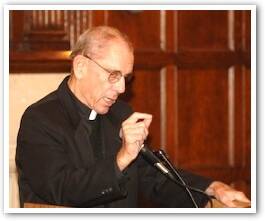

Father James V. Schall, S.J., is a California-based Jesuit teacher, writer, and philosopher. In December 2012, he retired as professor of political philosophy in the Department of Government at Georgetown University after 35 years there. After two years in the army, he joined the Society of Jesus in 1948, earning a B.A. from Santa Clara University. He holds an M.A. in philosophy from Gonzaga University and a Ph.D in political theory from Georgetown University.

A prolific writer, Father Schall is author of more than 30 book and editor or co-editor of eight others. He is also a regular columnist for various Catholic and academic periodicals. As a writer, Father Schall’s work consists largely of essays and essay collections exploring the pleasure of knowledge for its own sake. His latest book, “The Classical Moment: Selected Essays on Knowledge and Its Pleasures,” is being published by St. Augustine Press. On July 17, I conducted the following interview with Father Schall by email.

Why did you write this book?

Books that are collections of essays, I think, almost write themselves. That is, you will write one essay on some topic, then another on something else. But there is a certain mood to what you are saying. After four, five, ten, twenty, forty essays, you begin to wonder if they should not be collected into a single volume. For any book that you write, it is first and foremost your hope that someone someday will read it. You have to be vain enough and humble enough to realize that surely someone will read it and realistic enough not to fall apart if no one does.

Who is your audience?

I once wrote a book called Christianity and Politics. About twenty years after it was published, I received a letter from a man in Brisbane, Australia. He told me that he came across the book in the back of his local parish church. He was a working man and he liked it. Somehow, the idea of that book making it to Australia made me realize what an “audience” was all about.

I recall that the great Father Joseph Fessio, S.J., while speaking of his experience in the publishing business, remarked to me that the remarkable thing about a book is precisely that you never really know who will read it or when or even if. Books are not exactly immortal as physical objects—my fifty-year old books are getting musty and brownish. But books have a way of remaining in place waiting for someone to read them. Christopher Morley once said that books are the most explosive things in the world. They just sit there waiting to go off. So your “audience” is whoever chances to read what you write. The idea of being able to say or to identify just who exactly will read your book seems to encroach on a divine privilege.

Once, as a Jesuit scholastic while I was teaching at the University of San Francisco, I walked across campus one evening with Father Edmund Smyth. He had a doctorate in history from Toronto, as I recall. He told me that it was not unusual that a good scholar might spend his whole life writing a book or two that only four or five others in the world could properly understand. But it was imperative that we have the freedom and leisure to have such works. In the end, they may be the ones that save us.

But I am not averse to having books, like those of C.S. Lewis or G.K. Chesterton, that sell millions of copies well beyond their lifetimes. I suppose Augustine’s Confessions is a classic example of such a book. Surely Augustine would be astonished at the “audience” that has, over the centuries, actually read the account of his life. Yet, even though the book is a colloquy with God, still much of the world still reverberates with wonder at this book. I have always thought that Augustine definitely had me in mind when he wrote his Confessions.

What do you want people to take from this new essay collection?

In a way, I do not want them to take anything with them. I want them to be amused, alerted, sometimes provoked, and always made aware of a look at things that they could never see but through my essay. Josef Pieper, that most insightful man, in commenting on Aquinas, once compared the essay form to the “article” form of St. Thomas. He pointed out that a good short essay and an article in the Summa were about the same length, three or four pages. The article set about to answer a question and give reasons for it, and to come to a conclusion. The essay, the “effort” in French, was looser. It could range widely over its subject matter. It did not have to be tightly argued. Yet, without the article, the essay is in danger of being fuzzy and frivolous, whereas, at its best, the essay contains genuine truths and deep feelings about human things, yes, even divine things.

In this book, you call the essay “one of the great inventions of the human mind,” frequently quoting people like Samuel Johnson. Has essay writing become a lost art today?

As a matter of fact, essays are flourishing on the internet, to where so many magazines and reviews have migrated. There are remarkably good essays on The Catholic Thing, Crisis Magazine, University Bookman, Catholic World Report, and a huge variety of various blogs and web sites. David Warren’s “Essays in Idleness” is worth a hundred TV news broadcasts. As far as I can see, the art of essay writing is blooming. And I would add, like anything else, to have one really good essay, and one good collection of essays, we need to have hundreds that are not so good, but still pretty good and worth reading. So essay writing is by no means a lost art. It may be more dynamic today than at any time in history.

But I do think the essay is one of the great inventions of the human mind. It is not the only thing the human mind has invented, but it is one that, in a brief space, manages to say many things, sometimes serious, sometimes lightsome, and sometimes whimsical. The essay is always on some aspect of our lot that we might otherwise have missed.

Johnson, of course, was one of the great essay writers. I like the classical essays, which seem to have been invented or at least popularized by Montaigne, though Cicero, Seneca, and Horace are still great models and preserves of the form. I do a series of columns over the years in The University Bookman called “On Letters and Essays.”

I associate letters and collections of letters—like Flannery O’Connor’s The Habit of Being—to belong together with essays. I am not sure if there is a collection of “Selected E-Mails,” but that is the form in which the old letter written on paper seems to be going. The good thing about a printed copy of a book and a journal is that you can hold them in your hands. Somehow, that seems more permanent, even though, if I want to look up Dorothy Sayers’ “Lost Tools of Learning,” I do that on some search engine even though I have several printed copies of it somewhere in my files.

Why is the essay still relevant?

Why is anything still relevant? I am afraid that I consider the criterion of “relevancy” to be one of the great causes of university mediocrity. It is a version of “keeping up with the Joneses.” The essay is a form, not the only one, to be sure, in which you can tell the truth. We need this "telling" perhaps more than anything in our culture. Moreover, as Chesterton said, there is no reason why an essay cannot be funny and tell the truth at the same time. He said in a memorable phrase, when he was accused of not being serious because he was amusing, that the opposite of funny was “not funny.” Many of the greatest truths we know are also funny and delightful. The essay should not be defended on the grounds that it is “relevant” but on the grounds that is one very concise way to tell the truth.

In your opinion, who are the best essayists currently in print?

The best essayist in the English language, as I have argued in my recent book, Remembering Belloc, is Hilaire Belloc. And the good thing about the essay is that it does not make any difference when the essay was written. There is absolutely no reason why “current writing” should be a criterion for our attention to essays. As I mentioned above, I think that we are living in a time of great flourishing of essays. I like David Warren, Joseph Epstein, Thomas Howard, Joseph Pearce, and George Will.

But when I sit down to read an essay, I usually reach for Belloc, C.S. Lewis, or Johnson. I refuse to be imprisoned by the now. I used to have a theme: “To be up-to-date is to be out of date.” If I write an essay, which I seem to have been doing most of my life, I do not compare it with “current writing.” I go back and read an essay of Belloc and shake my head and say to myself, “This is just great!” I do the same when I reread Hazlitt’s “On Going a Journey.” I ask myself, “How could anything be better?”

I should also say a word about Plato. If someone asks me “Is Plato relevant?” I almost despair. Sometimes I am not sure anything else but Plato is worth reading. The subtitle of my book Idylls & Rambles—a title that obviously comes from Samuel Johnson’s essay collections in The Idler and The Rambler—is “Shorter Christian Essays.” Thus, I tend to distinguish between long and short essays. My love is the short essay. Some of my best essays though are longer ones, especially on Plato. In many ways my best academic essay is entitled “On the Death of Plato: Some Philosophical Thoughts on the Thracian Maidens,” which is found in my collection, The Mind That Is Catholic.

I might add that I have been writing a series of essays on Chesterton for many decades now. Some of these are collected in CUA Press’ book “Schall on Chesterton.” I would fail if I tried to explain the wonder of Chesterton’s essays. I have a number of books that are more academic and not just collections of essays: At the Limits of Political Philosophy; Reasonable Pleasures; The Order of Things; Reason, Revelation, and the Foundations of Political Philosophy; The Modern Age, and The Regensburg Lecture. But I do love the essay and all books begin with some small sketch that is really an essay.

You often mix pop culture references into your essays, citing Charlie Brown and Snoopy as philosophers alongside Aristotle and Augustine. Why?

The short answer is that Charles Schulz is, in fact, a very good philosopher writing in a format that may be off-putting to the purist who cannot imagine true philosophical insight to appear in a cartoon. Actually, I never particularly liked Snoopy. I found the real core of Schulz in Charlie himself, particularly in Lucy, but also in Linus, Schroeder, and the others. I see nothing to prevent my citing any insight I might come across if it makes what I am saying clear or if it says the truth in a way that few would otherwise miss.

Again that is the genius of the essay form. You can include anything in it if it makes the truth in its own way. Msgr. Robert Sokolowski, who is probably the best philosopher among us, has a wonderful book entitled Pictures, Quotations, and Distinctions. He points out that our ability to cite someone else in the context of our own thinking or writing enables us to call on the rest of the world as we think our way through our own understanding of it. When you write, you write among both friends and antagonists. Of the latter, you want, as Aquinas would advise, to find the truth in what they are trying to say. Of the former, you are grateful that someone else has seen a truth before you did, or explained to you why it was so. So to “mix” these references is simply to be honest. Someone else really did guide you to some truth or insight that you might have otherwise never noticed.

You retired from the classroom after 35 years as a popular Georgetown professor teaching classical political philosophy. If you could pick only one lesson that students took from your writing and teaching, what would it be?

The overwhelming thing, I suppose, is a lesson from Aristotle: We cannot have many good friends in this life, because true friendship is for a few in a complete lifetime. Yet, and this is the Christian element, we still have met so many fine and lovely students that we only began to know. They each had to go on to their own lives. Yet, reality somehow cannot be at rest if it does not ultimately include this completion of what was also begun in this life. This is why I have written so much on immortality and resurrection. There is already much of this wondering in my first book, Redeeming the Time.

Still, with regard to students, I think that my book Another Sort of Learning best takes us to the lessons that students teach us. The function of a professor is primarily to teach the truth, not “his” own private truth. Students are just out there. When you walk into class the first day of a semester, they do not know you nor you them. They are not there so you can entertain them, though you hope that they laugh at your jokes, even if they are not particularly funny. You do not “own” the truth. You are there as someone who has read and hopefully pondered things that they never thought of, the things that are. You are there to enable them, as Yves Simon explained, to arrive to the truth faster than if they would flounder about by themselves.

So you tell them about those books and writers who have helped you. Another Sort of Learning is full of books to read, books that probably no one ever told them about, books, as I say, “to keep sane by.” But you read with them. They have heard of Aristotle, perhaps, but have no clue about him. So you just begin to read him. “Stick with me,” you tell them, “you will see.” Most often they do.

But you cannot “make” them see. It is something that must come from within them as it has to come from within you, but about something that is not you, about what is. So you look for what I call “the light in the eye.” You look for the day that the young man in the back of the room suddenly seems to perk up. He seems to see that Aristotle or Plato or Aquinas has something to say.

You tell them that one of the things you want them to learn from your course is that the most exciting things they will ever encounter came from hundreds and thousands of years ago. They will find nothing quite like it and they know it. When they see this, your job as a professor is basically over. That is always why I tried to end my classes with Plato. As I say, there is no such thing as a university in which the reading of Plato is not constantly going on.

Outside of knowledge for its own sake, what is the greatest love in your life?

Goodness! “Knowledge for its own sake” is again Aristotle. Strictly speaking, we can only love what is loveable. Ideas we know. We want to know if they are true or not. But we can only love a person. And the love of persons includes, as Aristotle said, reciprocity. Once we realize this fact, we can begin to wonder why we are told that the first commandment is to love the Lord, our God.

This gets us to Aristotle’s problem of whether God is lonely. We then read in Aquinas that there is otherness in God. A chapter in Redeeming the Time was called “God Is Not Alone.” It was the chapter on the Trinity. I once heard the Australian writer and publisher, Frank Sheed, a famous speaker at Hyde Park Corner in London, say that the one topic that always caused silence and attention in these most critical listeners was that of the Trinity. I suspect the greatest love of one’s life is the discovery of the origin of love in the Trinitarian inner life of the Godhead, the only possible place that the friendships we begin in this world could be completed and abide.

Any last thoughts?

We live in a time in which the very essence of our republic and our reason are being overturned in the public order. They are replaced by the voluntarism of which Pope Benedict spoke so clearly. All turmoil in the public order begins in the hearts and minds of the dons, clerical and academic. My last thoughts are those of Chesterton concluding Heretics in 1905, that in the end, the only ones left to uphold reason in the modern world will be the believers. We are seeing this happen before our very eyes, but few notice because few want to know.

Sean Salai, S.J., is a summer editorial intern at America.