"Look, I’m very aware of the fact that no reviewer is going to be able to stop the Watchman juggernaut" Entertainment Weekly Senior Editor, Tina Jordan, opined last week. "I just want people to understand two things: First, this is all about the money. And second, reading Watchman will forever tarnish your memories of one of the most beloved books in American literature."

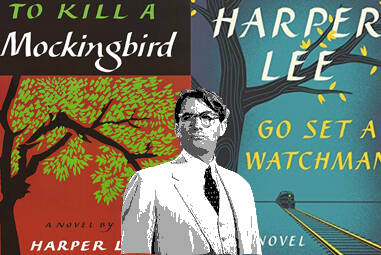

Jordan's review struck me because it perfectly encapsulates the very odd mixture of cynicism and naivete that has characterized so much of the coverage in general of Harper Lee's 'newly discovered' novel. Full disclosure here: I have not yet read Watchman, but I am one of the countless people—I think the technical term is "gazillions"—who have read and loved To Kill a Mockingbird and seen the film. Thus I am eminently qualified to make the following pronouncements. ;o)

In all seriousness, though, I'm less concerned about whether Watchman stands or falls on its own merits (by nearly all accounts, it falls); instead I'm fascinated by the strange sense I'm getting from the coverage that Mockingbird is somehow tainted by the publication of Watchman. Atticus, Scout et al are as beloved as any characters in American fiction over the past century, so there is an understandable sense of ownership that we all have. At the same time there seems to be an undercurrent to some of the criticism that suggests that we may have been duped, that somehow Harper Lee has committed a crime of the imagination in creating an alternate story in which Atticus is not the saintly crusader for racial equality in Mockingbird but instead an aging father who is troubled by the changes brought on by the civil rights movement.

Is this Harper Lee's The Education of Little Tree moment, in which we are scandalized to discover that the author of a beloved childhood story is not who we presumed?

Hardly. Yet, while it's touching that readers are so devoted to the characters set forth in Mockingbird, it's slightly disconcerting that anyone would allow their love of such a beautifully rendered story to be diminished by an author’s different imagining of it. Bob Dylan’s version of “Like a Rolling Stone” in waltz time—released decades after the original—is an interesting window into the alley ways he traveled before settling on the final record as we know it but it doesn’t alter the original’s epic greatness in the least.

Granted, given the new book's murky origins, Tina Jordan’s first caveat, “This is all about the money,” could be true. And it would be sad to think that the notoriously publicity-averse Lee, now 89 and reportedly less lucid, had been taken advantage of. The truth is we probably would’ve seen Go Set a Watchman at some point in the not-too-distant future anyway.

My only fear at this point is that with the upcoming release of JD Salinger's unpublished work, we don't discover a long-lost novel in which Holden Caulfield grows up to be "Mad Men's" Roger Sterling.

Thanks Beth. That's an interesting insight into a Southern reality that people like me from the North wouldn't necessarily get.

Bill