There are two kinds of people in the world: those who are Irish, and those who wish they were. At least that’s how the saying goes—and I’ve heard it quite a few times since I married an Irishman a few decades ago.

Most of the time, I dismiss such bon mots of Irish pride for the blarney that they are and happily lay claim to my Sicilian-Roman heritage. (This is especially true around dinner time. Who would choose boiled potatoes and beer over a plate of Linguine Puttanesca and a glass of Chianti?) But when it comes to poetry, I must confess to full-fledged Irish Envy.

Ireland has more than its share of “saints, scholars, and schizophrenics,” as a celebrated study of Western Ireland has demonstrated. There is something about Ireland, with her wild terrain, deep mythology and dark history, that tends toward mystery. It makes sense that such a culture would produce people with extravagant minds. It also makes sense that it would produce more than its share of poets. Lovers of language and purveyors of song, no one can wield and weave words quite like the Irish—even in a tongue that is not their own. Irish lore is rife with poetry. The Ancient Makers knew there was magic in chanting “the right words in the right order” (the formula Coleridge devised to describe poetry), and Ireland’s Modern Makers know this, too.

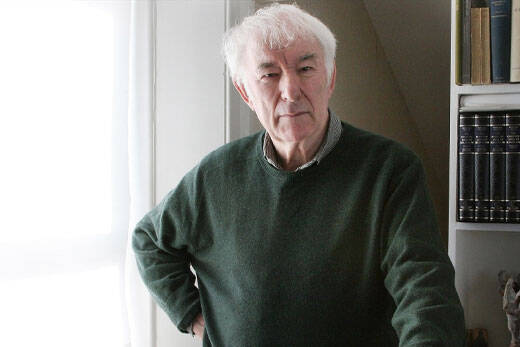

Sadly, the most celebrated among those Modern Makers, Seamus Heaney, passed out of this world on August 30, 2013. Winner of the Nobel Prize for Poetry (1995), author of 13 major collections of poems (and many smaller collections besides), four collections of prose, two plays and multiple translations of major Western texts, Heaney was among the most productive and lauded of living poets, Irish or otherwise. He was also among the most beloved. In addition to being a poet who wrote deeply human, accessible poems, he was a dedicated teacher of young writers, a generous friend, a faithful husband (married to fellow poet, Marie Devlin, for nearly 50 years), and a devoted father. W.B. Yeats, another celebrated Irish poet (one to whom Heaney is often compared), wrote that human beings are forced to choose between “perfection of the life, or of the work.” Heaney seems to have proven his predecessor wrong. He lived as well as he wrote.

For the past several weeks, Ireland has grieved Heaney’s loss publicly and without restraint. The day of his death, the radio stations played recordings of him reading his poems. As an Irish friend confided to me in an email she wrote that morning, “that voice and those words that are usually so comforting are so heartbreaking today.” Friends of Heaney, including august writers Thomas Kinsella, John Montague, Peter Sirr and Paul Muldoon, in speaking of him had to stop as they were overcome by their sorrow.

The rest of the world grieves Heaney as well, for unmistakably Irish as he was, we know he belonged to us all. Even people who never knew Heaney personally but know him through his work—people like me—feel a keen sense of loss and understand we are all poorer for his passing. Over the past few weeks, Heaney’s poems have haunted me. Lines come to me unbidden, out of the pure blue—like these from his poem, “Clearances,” chronicling the death of his parents:

And we all knew one thing by being there.

The space we stood around had been emptied

Into us to keep, it penetrated

Clearances that suddenly stood open.

High cries were felled and a pure change happened.

A “pure change” has happened to us all as we look into the emptied space left by Heaney’s absence, the sudden silencing of a voice that has been with us for nearly five decades (so familiar, “so comforting,” as my friend said). Since 1966, with the publication of his first book, Death of a Naturalist, Heaney has been telling us his story—of his growing up in rural County Derry, the eldest of nine in a big Catholic family, of his explorations of the little world he inhabited and what its mysteries might mean, of his discovery of his vocation as writer (rather than farmer or IRA soldier), of the Troubles that afflicted his country and led to bloodshed and murder and self-sacrifice, and of the power of poetry to name the graces we are blessed by and to redeem our most grievous losses. Heaney had the poet’s gift of being able to make the particular universal—to tell his story, in all its concrete detail, while simultaneously telling us our own.

Heaney’s poems of childhood—that universal condition we all share—are particularly poignant, capturing as they do our own discoveries of pleasure, of beauty, of love, and, inevitably, of our mortality. (And how often these discoveries occur to the child at the very same moment.) In the poem “Blackberry Picking,” he describes in glorious detail the eager pleasure of searching for blackberries in high summer, anticipating the buckets full of berries he and his siblings would bring home, gorging themselves on the “flesh / sweet like thickened wine,” and “hoarding” them in the barn for future days. Sadly, though, the ritual begun in such joy would end in desolation, as the children would find “a rat-grey fungus glutting on our cache”:

Once off the bush

The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour.

I always felt like crying. It wasn't fair

That all the lovely canfuls smelt of rot.

Each year I hoped they'd keep, knew they would not.

The child’s pleasure in satisfying his “lust for picking” and his appetite inevitably leads to this sober knowledge—beauty dies, pleasure ceases, nothing lasts in the end. These are grim thoughts for any child to harbor—but such is the nature of the human that we cannot help but hope, from moment to moment, day to day, and year to year. Hope is what keeps us from despairing in the face of death, and poetry speaks the language of hope better than any other art I know. With each re-reading of this poem, we accompany young Seamus and our childish selves in the ritual search for a perfection we know we can never possess. And we reenact this fruitless/bootless search, this hopeful/hopeless quest, joyfully. Because of Heaney’s art, we accompany ourselves singing.

Heaney’s most well-known poem is the one that might seem, at first glance, to be the least universal, “Digging.” A poem about young adulthood, rather than childhood, Heaney dramatizes the moment when he discovered his vocation as a writer. This epiphany comes to him as he sits as his desk looking out of his window and watching his father dig peat in the field below. Since few of us have grown up on farms in rural Ireland, and few of us decide to become writers, it might seem a stretch to claim that “Digging” describes our own sudden knowledge of our selves, our limitations and our talents. Yet Heaney’s poem speaks to us through its particularity, immersing us in Irish earth and yet piercing through the veil of appearances, to reveal to us the time-honored human journey toward maturation, revelation and self-knowledge:

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.

Under my window, a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging. I look down

Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.

The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked

Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade.

Just like his old man.

My grandfather cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toner’s bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, going down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

Between the opening and the closing of this brief, 31-line poem, the young Heaney goes from idle observer of the world to active participant in his chosen arena of life. In the opening stanza, his pen is poised, ‘resting’ in his hand, “snug as a gun”—a terrific simile suggesting the latent power in the pen the boy has not yet learned to use. By the end of the poem, the pen has transformed into a very different sort of tool—a spade. But unlike the spades used by his father and grandfather to dig in the earth, the pen is a spade that probes the heart and mind, digging into memory, history, and the mystery of identity.

Much of the poem focuses on the past—the work of his forbears, their precision and craftsmanship, “nicking and slicing neatly,” their heroic strength, “heaving sods over their shoulders” like the Gaelic Giants they were to the small boy Seamus. He has long known himself to be different—“I’ve no spade to follow men like them”—but he suddenly discovers essential ways in which they are the same. Their pursuit of excellence, intimacy with the gritty reality of the place they come from, what Jesuit poet G.M. Hopkins describes as the this-ness of life, “The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap / Of soggy peat”—these are their common passions, only Heaney will lay claim to them with words. The young man’s—and the universal—rite of passage is complete. The final lines of the poem launch the passive, past-obsessed boy into his own future as he concludes with this resolve, “The squat pen rests. I’ll dig with it.” And dig he does. Heaney remained faithful to his promise for the next 50 years—until now.

Three years ago, I had the pleasure of doing a podcast/interview with Americamagazine when Heaney’s then-new (and, as it turns out, his final) collection was published, Human Chain (2010). When asked by the interviewer, America editor Tim Reidy, to identify a favorite poem in the book, Heaney’s strange poem “A Herbal” immediately popped into mind, as it contained these marvelous lines:

I had my existence. I was there.

Me in place and the place in me.

What strikes me about these lines is the bold claim they made then and that they make now. Heaney wrote them after suffering a stroke that nearly killed him, and they seemed to me to constitute a declaration of independence and an absolute refusal to fear. With its insistent repetition of “I” and “me,” the lines proclaim the inviolable power and sanctity of the eternal “I AM.” Whenever death comes (and come it will), whatever death might do to my body, Heaney seems to say, it cannot take away from me the fact that I lived—and not only lived, but lived in the here and now that is Ireland, my heart and my home. These are words we might all live and die by, no matter what country we might call our own.

The American poet Walt Whitman once wrote that “the proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it.” Heaney has been absorbed by his country all right, and claimed by most of the countries of the world, as well. Wherever poetry is valued, he is revered and mourned. In addition to the many eulogies offered, the hundreds of tributes penned, the public readings of his poems, people from around the world have been writing poems honoring Heaney’s life and his art. I’d like to close this piece by offering one such poem, a sonnet I wrote in homage to Mr. Heaney some years ago. In addressing Heaney as “Saint Seamus,” the poem calls attention to the sacredness of the Word, the instrument Heaney used to honor and celebrate the world, and suggests the sacredness of the pursuit of poetry.

Homage to Saint Seamus

“I rhyme to see myself, to set the darkness echoing.”

Seamus Heaney

For years I’ve knelt at your holy wells

and envied the cut of your clean-edged song,

lay down in the bog where dead men dwell,

grieved with your ghosts who told their wrongs.

Your consonants cleave my soft palate.

I taste their rough music and savor it long

past the last line of the taut sonnet,

its rhyming subtle, its accent strong.

And every poem speaks a sacrament,

blood of old blessing and bread of the word,

feeding me full in language ancient

as Aran’s rock and St. Kevin’s birds.

English will never be the same.

To make it ours is why you came.

"Homage to Saint Seamus” admits openly the Irish Envy I confessed at the outset of this essay—but the poem finally arrives at the joyful discovery (just as I did) that poets like Seamus Heaney bless and liberate language for all of us. We don’t have to be Irish to lay claim to great poetry. We only have to be human.

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell is a poet, professor and associate director of the Curran Center for American Catholic Studies at Fordham University.