Pune, India. I am at the end of more than two weeks here in Pune. I resided during my stay at the Jnana Deepa Vidyapeeth (something like, “The School of Wisdom, Light of Knowledge”), home to the Jesuit de Nobili College and Papal Seminary, moved here from Kandy, Srilanka, soon after Indian independence in the late 1940s. Here large numbers of diocesan and religious order seminarians study, as well as a number of nearby congregations of sisters. The campus is large and serene, an oasis removed a bit from the increasingly busy and crowded city outside the gates. The students are, as one might expect, a wide mix: scholars to be alongside those eager to get out into their ministries, and as at any seminary, the task is to show, again and again, how and why times of quiet study matter. As teachers and scholars, the faculty face the major challenge of making coherent a variety of streams of thought and values: the traditions of Western and Christian philosophy and theology as understood and governed by Vatican norms; traditional and contemporary Indian philosophies and theologies that often seem squeezed to the edge of the curriculum; the intellectual and spiritual way forward for the Indian Christian community, thought and argued out on this campus, among its present and future intellectual leaders, in today’s swiftly changing India. But perhaps the greatest challenge is more mundane: it struck me that these faculty are entirely too busy – too much administration and too much teaching – and thus have a hard time continuing the thinking and writing which is, in many cases, closest to their hearts. As the worldwide Church of the future looks to India for guidance, it will be necessary to give its best minds more time to do their research and writing.

Since I was in town, I received some other invitations as well, to speak several times outside the seminary context, for example, at the venerable Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute on my new project in Mimamsa (Hindu ritual thinking), and at Pune University, where I was asked to speak on the state of religious studies in America today. I was impressed by the intense interest of faculty and students in thinking through issues in the study of religion, and in seeking models for this study that are not merely imported from the West, but fitting to the Indian intellectual scene. The issues took on a new life this past week, as a controversy sprang up here in India and then globally, over Penguin-India’s withdrawal from sale of Professor Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternative History, after a lawsuit was lodged arguing that the book is offensive to Hindus. By an old British-era law the case could be brought, and Penguin-India decided to avoid the lengthy legal battle that would ensue, by withdrawing the book and promising to destroy remaining copies. Opinion in the press is divided, and on the streets too. On one nearby campus, I met a group of college students who observed a moment of silence yesterday to lament this blow to freedom of speech. While offense, particularly needless offense, to people’s religious faith is hardly commendable, and cultural standards differ regarding what is offensive, it is a dangerous road to travel, if we start banning books because someone or some group is offended. Better, I suggest, would be a robust intellectual response, demonstrating a book’s limitations and offering counter-arguments. I hope someday to meet some of the aggrieved proponents of the case, to explore further what they did and do think of the whole matter, as a religious and not political event.

On a more positive note, I had the occasion to travel to the famed Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute, a spiritual and busy place that seems to have outgrown its space, with the many students coming and going while I was there. I was honored to spend some time with the internationally known BKS Iyengar, one of the foremost of yoga teachers in the world today. Recently he received the highest civilian honor the Indian government can offer, the Padma Vibhusan. At 95, he is impressively alert and agile, and it was fascinating to hear his musings on how his own simple practice and teaching of yoga, at his teacher’s command, led to this worldwide movement. Slow and sure, focused commitment makes a difference, we are reminded, when politicians and the press are rushing to decide religious matters.

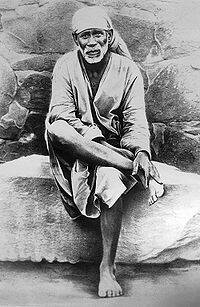

My other great excursion was a kind of pilgrimage, out to the town of Shirdi, about 150 kilometers from Pune. What had been a small village, that has grown up to be a major destination for pilgrims, for it was home, a century ago, to Sai Baba, the simple and mystical holy man, perhaps a Muslim, perhaps (too) a Hindu, who lived much of his life there. Amazingly, nearly 100 years after his death, his tomb (samadhi) is said to receive about 50,000 visitors a day. We – myself and two professors – spent about 24 hours in the area, amidst the great crowds of pilgrims of every age and background visiting the village (many times in the monumental hotels surrounding the central area). Early in the morning we joined the line of visitors to the tomb of the saint, and wound our way above and below ground until we reached the tomb itself, where we could linger for just a moment. The walls of the shrine itself, and its environs and the bookstores, are full of claims about Sai Baba, the effectiveness of prayer to him, and the exalted nature of his divinity; but it seems to be left to individuals to decide for themselves how to think of and honor him. I know that some at the seminary, though living in the vicinity for decades, have never visited Shirdi. A few at least were politely uncomfortable with the very idea of Christians visiting this shrine of the saint. But in my writing and occasionally, as this time, on my feet, I believe that going to the other, to other holy places, as a simple pilgrim, is a necessary move – particularly in an era when it is tempting to place it safe and to withdraw into one’s own religion and see other religions are forbidding, foreign zones. On this visit, I am sure I was experiencing the grace of God. For God does not hesitate, I think, to dwell wherever holy men and women have lived, and wherever holy pilgrims manifest their faith. Whatever the politics and cultural tensions of religious pluralism today, figures like Sai Baba remain a gift for us all, a reminder that deep spiritual insights and lives draw together rather than divide us. It is not entirely fanciful to ask: In 2014, what would Sai Baba do?

More after the next step in my journey, to Srilanka.