Cambridge, MA. I was asked several times during my ten days in China how I would compare China to India; repeatedly, I had to answer that this would be a very difficult comparison to make, given that this had been my first visit to China, while I’ve been going to South Asia for 40 years. What I experienced at age 22 in Nepal, where I arrived in July of 1973, had to be a different kind of formative experience for me than visiting China at age 62. Even if I accept the invitations to come back and spend weeks or months in Beijing or Hangzhou, and build my relation with the most interesting and impressive professors and students I met, there is no chance that I will invest in China the same interest and attention that I’ve given to India and Hinduism over the decades. Still, I’ve ever been one to insist (including in this space, as in my series of learning from the Book of Mormon) that no interreligious encounter is impossible, entirely strange or alien; no one reading this blog is incapable of learning across the borders of religions. Better yet, even as amateurs, we can begin to learn across cultural and religious boundaries, and make good progress even if unlikely ever to be expert. Since I am not adept at geopolitics or the great issues of the day or ready to predict the future of China in the 21st century, etc., I turn back to history, and inward to literature and religious practice. So here are several of my own concluding reflections on China, to finish off the reflections offered in my first and second entries.

First, it is not insignificant that China hold such an honored place in Jesuit history. I quoted during one of my lectures in Beijing the words of Nicolas Trigault, SJ (1577-1628). In his 1615 introduction to Ricci’s diary, Trigault gave this comprehensive judgment on China:

Of all the pagan sects known to Europe, I know of no people who fell into fewer errors in the early ages of their antiquity than did the Chinese. From the very beginning of their history, it is recorded in their writings that they recognized and worshiped one supreme being whom they called the King of Heaven, or designated by some other name indicating his rule over heaven and earth… They also taught that the light of reason came from heaven and that the dictates of reason should be hearkened to in every human action. Nowhere do we read that the Chinese created monsters of vice out of this supreme being or from his ministering deities, such as the Romans, the Greeks, and the Egyptians evolved into gods or patrons of the vices…One can confidently hope that in the mercy of God many of the ancient Chinese found salvation in the natural law, assisted as they must have been by that special help which, as the theologians teach, is denied to no one who does what he can toward salvation, according to the light of his conscience… That they endeavored to do this is readily determined from their history of more than four thousand years, which really is a record of good deeds done on behalf of their country and for the common good. The same conclusion might also be drawn from the books of rare wisdom of their ancient philosophers. These books are still extant and are filled with most salutary advice on training men to be virtuous. In this particular respect, they seem to be quite the equals of our own most distinguished philosophers.

High praise indeed. I do not agree that one can conclude anything decisive about China and India, such that one would be preferable over the other in some absolute terms, but were I to study China, I would certainly want to think more about how Francis Xavier died trying to enter China, how Trigault and other early Jesuits found so much to admire in Chinese culture, philosophy, and religion - and, perhaps, how China much more recently inspired Teilhard de Chardin.

Second, even if I could not (at this point in life) learn Chinese in any serious, scholarly way, I would want to read more Chinese poetry as a starting point. The clarity, utter calmness, subtlety of emotion, and harmony with nature come across even in translation. Consider this classical poem about the West Lake in Hangzhou, a wonderful place to visit:

Now spring is here the lake seems a painted picture, / Unruly peaks all round the edge, the water spread out flat. / Pines in ranks on the face of the hills, a thousand layers of green: / The moon centred on the heart of the waves, just one pearl. / Threadends of an emerald-green rug, the extruding paddy-shoots: / Sash of a blue damask skirt, the expanse of new reeds. / If I cannot bring myself yet to put Hangzhou behind me, / Half of what holds me here is on this lake. (from A.C. Graham's Poems of the West Lake: Translations from the Chinese, London: Wellsweep, 1990, as found in the China Heritage Quarterly)

Being “held” by this lake, drawn into it as if into a work of art seen for the first time and impossible to forget, is a precious starting point. The smallest point of contact, intimately played out in color and light and touch, is enough to make much learning possible. Or this excerpt from a modern poem by Marie Pansot, “Evening”:

…On the lake of the poets a stone lamp flickers. / It casts eight moons dancing, casting doubt / on the moon that rides above the winter air. / Ice thaws in a poet’s throat; the springing / truth is fresh. It wakes taste. The taste lasts. / Language floods the mud; mind makes a cast of words; / it precipitates, mercurial, like T’ang discourse / riding the tidal constant of its source. (“Hangzhou, Lake of the Poets” from The Green Dark, as found here.)

Again, the passing of winter into spring, a taste that does not fade right away, is enough to make real learning possible.

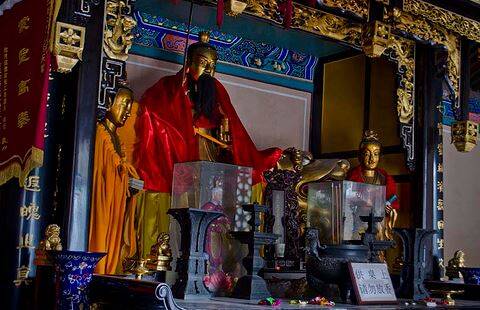

Third, had I the time, I would probably take up the study of Daoism, that very old and very Chinese tradition. I had mentioned in a previous blog visiting the White Cloud Temple in Beijing. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Cloud_TempleWhile I had visited several impressive Buddhist temples, it was this Daoist shrine that seemed to be most richly complex, bringing together a sense of the universe and the universal interconnectedness of things, and the harmony with the microcosm that is human being. In the many individual shrines in the temple — which, if properly understood, seem a primer of Daoism as a whole — one meets deities and saints, teachers and healers, philosophers and mystics. I could easily be at home there, I think. I noticed in the temple several deities that seemed very gracious, even (from the translation of the note to visitors!) Christlike; I cannot say for sure, of course, but at least this intuition is a starting point. And here again, I would begin with a poem, such as this one I discovered today at a website for Daoist poetry:

Attainment of the Prime of the One / Is not a gift from Heaven. / Realization of the Great Nonbeing / Is the state of highest immortality. / Light restrained, a hidden brilliance, / The body one with nature: / There is true peace, won but not pursued. / Spirit kept forever at rest. / In serenity and beauty: this is perfection! / Body and inner nature, hard and soft, / All is but cinnabar vapor, azure barrens. / One of the highest sages – / Only after a hundred years / The tomb is discovered empty. (Mysterious Pearly Mirror of the Mind by Jiao Shaoxuan, 817 CE; as quoted from The Daoist Experience, edited by Livia Kohn, 1993)

I share all this with you in part, again, to put in place and as it were close off my trip to China, even before jetlag is nearly done with, and in part to try to convince you, once more, that in our personal ways, we can always learn across religious boundaries. Our history, our literature, our holy places — all can be starting point. Try it, encountering some religion, in what you see or read or actually visit.