In my "other life" as a musician/songwriter I've been fortunate to have some really gratifying experiences sharing stages with personal heroes like Roger McGuinn of The Byrds, Shane MacGowan of The Pogues, bands like NRBQ and others. Strange as it might sound though, one of the most memorable moments in my musical life came as a magazine editor overseeing a profile on Pete Seeger.

In the spring of 2001, I was the managing editor of a now-defunct print magazine called Book. The concept behind the magazine was that all the major forms of entertainment—music, TV, movies—had magazines that covered them for a general audience (i.e.: Rolling Stone, TV Guide, Entertainment Weekly/Premiere). Books however did not, and that's where we came in. If John Irving, Anne Rice or Amy Tan had new books coming out, they would be on our cover and profiled within.

Unlike rock musicians or movie and TV stars, however, authors—while generally smart and insightful—are a pretty cerebral bunch whose lives don't often make for scintillating copy. There are notable exceptions—Hemingway, Fitzgerald—but one of our biggest concerns was avoiding stories like this:

Book: Can you tell us about what it was like working on your new novel?

Famous author: Oh, sure. Well for the past 8 years or so I got up early, sat at my computer and typed from 9:15-12:45. Then I took an hour for lunch—usually soup and a sandwich—and then was back at the computer typing until dinner.

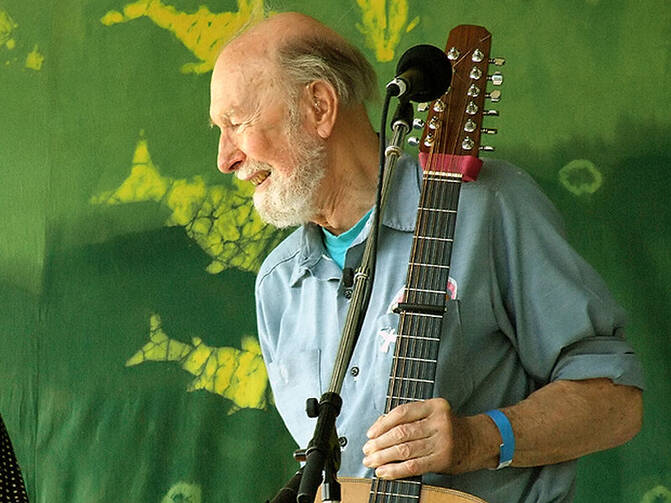

Finding interesting ways to cover "the reading life" for a general audience was a constant challenge. So when I noticed that Pete Seeger was releasing his aptly titled Pete Seeger's Storytelling Book it ignited an idea. Here was an "author" who considered the act of sharing stories to be a "near-sacred tradition" whether it was in the form of a book, a movie, a song or a simple conversation. In early folk music circles—before the explosion in recorded music and broadcasting—songs and stories were a form of currency that was shared, passed along and adapted. Seeger was a living link to that tradition and—in a pre-blogging age—wanted to democratize the act of storytelling by teaching us how it's done and encouraging people to believe we all have stories worth telling. I was sure he would make for a compelling profile and, at the very least, I was pretty confident that Pete didn't spend day and night sitting at a computer

Seeger had incredible stories of his own to tell. He'd hopped trains and sang in saloons with Woody Guthrie. He'd had hit records in the 1950s with The Weavers ("Goodnight, Irene," "On Top of Old Smoky"). At the height of his career he'd been blacklisted and called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee where he refused to cooperate and name names. He was instrumental in adapting and popularizing the traditional spiritual "We Shall Overcome." Pete also became involved in the civil rights movement alongside Martin Luther King Jr. His songs “If I Had A Hammer” and “Where have all the Flowers Gone” became standards around the world.

Seeger was the senior statesman of the folk music world when its young star, Bob Dylan, exploded onto the cultural stage. He was also there in 1965 when Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival and was infamously (and incorrectly) accused of wanting to cut the power off in protest (poor sound quality was to blame, not Dylan's move to electric instruments). His song "Turn, Turn, Turn"—adapted from Ecclesiastes—became a smash hit for The Byrds and was a cornerstone of the "folk rock" movement. The list of accomplishments was impressive.

Pete’s most incredible feat though was the fact that he was the real deal. People all around him had profited mightily on the folk music movement he helped foster but Seeger had eschewed fame and fortune to live a life of integrity and principle. He gave away much of the royalties he could've earned from songs like "We Shall Overcome" to non-profit organizations and charities. He continued to live simply with his wife of 70 years, Toshi, in the modest log cabin he'd built for them overlooking the Hudson River in 1949. The ideals he'd espoused all his life continued to be present in his championing of the clean up of the Hudson River through his Clearwater organization. His participation in the Occupy Wall Street movement was just his latest incarnation in a lifetime of social and political engagement. Seeger's life was almost Forrest Gump-like, except that he was real and his participation in hugely important cultural and political events wasn't a tangential fantasy, it was significant and ongoing.

The man was a living and breathing American treasure as far as I was concerned. Though I wasn’t interviewing him or writing the profile myself, I wasn’t planning on staying on the sidelines either. When the book’s publicist suggested I contact Pete by phone to coordinate the interview and photo shoot I immediately borrowed the only private office at the magazine and closed the door so I wouldn’t be interrupted. Turned out I was interrupting Seeger. His wife answered and said he was out chopping wood (at 81!) and asked me to hold on.

When Pete finally got on the line, it was quickly clear that he was exactly who I'd hoped he'd be. He was incredibly kind, smart, interesting and extremely humble. His hearing wasn’t great and his conversation rambled a bit, but for 81 he seemed extraordinarily vibrant. We talked for 45 minutes on a wide range of topics—his career, his activism, the Newport incident with Dylan. It was like having a private conversation with history itself.

The reporter submitted his copy a few weeks later and, amid the quotes I needed to check, I noticed a paragraph about Seeger’s recent attempts at songwriting. "I get ideas and don't know how to complete them,” he said. “I'll come up with a good line, but no song for it. For instance, I have a line for an Irish song that goes, 'And who'd believe/ I'd feel so good/ To discover I'd been wrong.' But that's all I have."

The songwriter in me liked the line and thought it could work well as a refrain. In the reporter’s notes I saw that Seeger was referring to a 1998 IRA bombing in Omagh, Northern Ireland. Over the next few weeks I did some research on the Omagh bombing and began to flesh out a melody and lyrics around Pete’s original idea. When the story was finally published, I called to say thank you and arrange to get him copies.

Once again, we had a wonderful, extended conversation about all manner of things. As it wound down, I was nervous about mentioning what I’d done with his song lyric. I wasn’t sure if he’d think it was presumptuous of me. Before we hung up I gathered up some courage and told him I had a bit of a confession to make. Fortunately, Pete was very gracious, excited even, that I’d taken his idea further along. He said he’d like to hear it. I told him I’d record it and send him a copy on a cassette (I don’t think Pete was very digital at the time).

A week or so after I sent him the song I received a simple, handwritten white postcard from Pete to the effect of “I really like the song, Bill. Let me know if you’re able to do anything with it!” and he signed it with his name and a doodle of a banjo. Ok, I thought, so Pete Seeger and I won’t be recording a duet anytime soon but at least he liked what I’d come up with.

A few weeks later I was surprised to receive another postcard from Pete. “Bill, I just listened to the song. I really like it but I’m just not sure what I could do with it now. Keep me posted on what you come up with. Pete.” I was a bit confused. Had he listened to the song again and written or had he forgotten that he’d written me the first time? I really had no way of knowing for sure until a week later when I received yet another postcard. “Bill, Thanks for sending the song. It sounds good, I’m just not sure I have the energy or time to do anything with it myself now though. Good luck with it! Pete”

It was pretty clear that Pete kept coming across the cassette and had forgotten that he’d already responded to me. I smiled to myself when I realized that this rapidly growing personal correspondence with my hero was the result of his fading short-term memory. In that moment, Pete transcended the iconic status he held in my mind as a singer, songwriter and activist and he became something altogether more profound. He became a real human being. He was a husband, father and grandfather who was moving into his 80s in much the same way my own grandparents had. Sure he’d lived through and contributed to some incredible times, but fundamentally he wasn’t any different from the rest of us. Wasn’t that precisely what the folk tradition and political activism that he devoted his life to was all about: discovering and sharing our common humanity for anyone with eyes to see and ears to hear?

Pete Seeger was more than an artist, he was an ordinary man with a lifelong vocation to a “near-sacred tradition” of sharing living things like stories, songs and a passion for justice. He did this for most of his 94 years on this earth in the hope that these living things would continue to take on new life for others and bring about a slightly more compassionate, peaceful and just world.

I was in bed after midnight on Tuesday when my phone lit up with a notification from the New York Times about Pete’s death. I didn’t click through to read the obituary; instead I laid back down, stared up at the ceiling and said a brief prayer for Pete. I prayed in gratitude for his life and, before drifting off to sleep, I also said a prayer of thanks for that one brief, tangential moment when I’d had the opportunity to share in that living tradition of song with him…even though I’m pretty sure he never would have remembered it.

Thanks Stanley...it's been percolating a while. B

That's great, Vince! Thanks for sharing it.