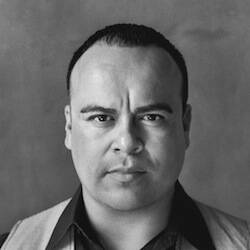

Rigoberto González, a Mexican-American poet, was born in Bakersfield, Calif., in 1970. At the age of two, his family returned to Mexico, where he remained until 1980.

His latest collection of poetry, Unpeopled Eden, deals with the poet’s grief surrounding what he describes as the second loss of his father. Voted one of the best poetry books of 2013 by Slate magazine, Eden discusses issues such as death and immigration, and as Jonathan Farmer of Slate magazine writes, “González strips his language down so far that it starts to sound like a collective voice—the voice, quite often, of a place emptied of emigrants killed or departed.”

In an interview conducted via email on July 28, the poet discusses the inspiration behind Eden, when he first fell in love with poetry and more.

When did you first become aware of your relationship with writing, particularly with poetry?

I was born in California, but at the age of two my family returned to Mexico. I didn’t become a reader however until my family moved back to California in 1980. I was 10 years old and desperate to learn English, which I knew was the key to thriving in the United States. I understood that not knowing English held my father back from getting a better job and made my mother fearful of venturing out on her own beyond the neighborhood. When we received letters in the mail, it caused my parents such anxiety not knowing what the paper in the envelope said—Were we getting thrown out of the country? Were we losing our place to live? My task was to learn the language and help my family with encounters with English that quickly became obstacles. Before this task, I felt somewhat unimportant and useless. Now I had a function. But once I began to access books I was unstoppable. My world became bigger and more interesting.

Eventually, I began to fantasize about becoming one of these people who wrote books and I continued to nurture that fantasy until I began to move among living writers—my teachers in college. At that point, the fantasy of being an author became a possibility, but I had to get there one page at a time. I think this is why poetry became so important to me—it helped me envision completion and sharpen my sense of artistry within the limits of a single page. Through poetry I learned about focus and music and craft—all elements that became essential when I began to write prose. And even though I write in many genres, I still think of poetry as my first love.

So to answer your question more simply, my lifelong relationship with writing began when I crossed the border as a 10-year-old and I looked at a sign on the street and wondered what it meant. My lifelong relationship to poetry began when my English tutor said to me, “Here, look at this: PAT PET PIT POT PUT. Every single one of those sounds is a word.” The desire to possess these tools—meaning and sound—have only continued to grow.

People often ask if I didn’t have these feelings as a Spanish-speaker. Well, Spanish wasn’t what made me unique in the house—English was. And since we didn’t have books in the house, it was those books at school that became important to me. I became a writer when I started learning English.

You were born in California but moved to Mexico and currently reside in New York City. How has living in these places affected your overall writing?

Leaving Mexico, and later leaving California, made me want to rebuild what I had left behind, made me want to preserve the memory of my experiences in those places that shaped the person I had become. When I write about my childhood, I always return home. When I write poetry, I usually go back to the complex and rich lives of the people who were part of my youth. Place as a cultural space is incredibly inspiring and fuels most of my work. It’s difficult for me to conceive writing anything without first locating that memory or image in a specific setting. Setting orients all the other elements—story, character, scene, dialogue, emotion.

I travel often, and I’ve been to some amazing places, and sometimes they sneak into the writing though it’s more like a cameo appearance—a mention of Italy or Scotland or Brazil. I am committed to situating my work mostly in Mexico and California, even though I’ve lived in New York City now since 1998. Just when I think I’ve become so much a New Yorker that I should write about it, I get pulled back to Mexico and the American southwest. Those are still fertile territories for me that keep me engaged. So my New York chronicle is forthcoming, but I’m in no hurry.

You mentioned in an interview with Publisher’s Weekly that one of the reasons you went into a creative writing program was “to imagine a cultured life.” Have you achieved that life in your writing?

Absolutely. To me a cultured life means having access to the intelligence, curiosity, beauty, mystery, imagination and insight that’s possible through books, through interactions with thinkers, artists and activists. It means contributing with my own voice and vision, and asking questions, challenging my own perspective. But it’s not all paradise in the writing program, and that’s what makes it even more appealing because I also learned how to handle disappointment, failure and exasperation. In a writing program I didn’t have to ever explain to anyone why I was reading a book or why I was writing such a story or poem—those were expectations. Since I was a bookworm from such a young age, how could I not commit to inhabiting this community of like-minded individuals?

Now, decades after the writing program, I am understanding how I’ve sustained that cultured life, not only as a writer, but [also] as a teacher, and as a citizen on Twitter. Knowing that I’m not the only one reacting to the atrocities and injustices of our times gives me comfort and also hope. I’m a writer, but sometimes I don’t want to write an essay or a poem—sometimes I just want to say what’s on my mind—vent, express outrage or recollect and muse. Again, even those sudden outbursts don’t need to come with caveats or explanations or excuses because I belong to a literate and open-minded tribe that knows where I’m coming from, and that even those not-so creative moments are necessary in order to get to a place of artistry.

What inspired your latest collection, Unpeopled Eden?

The death of my father. I have been having a very long conversation with my father over the span of many books. I lost him twice: when I was about 13 years old and he remarried to rebuild his life without me; and when he died. His death gave me some clarity. Before then I wrote to him and about him through the language of anger and betrayal. Now his second wife had lost him also. In order to avoid writing an intensely personal and private book—and I knew it had to be poetry, no other genre was going to allow me to navigate such intense grief, not at that moment in my life anyway—I looked at the experience of losing a father through a number of lenses: death, desertion, war, divorce, migration, etc. A weight was lifted off my shoulders knowing that this was a burden upon the world, not only on me. It’s interesting because the farther I thought I was getting from my father’s death, the closer I was getting to it. And next to this very painful reality were other painful realities that I wanted to explore—I didn’t have to impose this personal loss on any other dynamic or experience because now I recognized it everywhere. The loss of a father, of guidance, of protector, of safety—it was all around me, and it had always been there, part of humanity’s history, which also showed me that I could survive it, as many others had. This is the hope embedded in my work. People look upon death and loss only as tragedy and sometimes forget that there is a stage of recovery, of healing, that necessarily comes after. I too was one of those people, and then, through the writing, I remembered that although I could not make my father’s absence disappear, I could build a kind of memorial—this book—to honor his passing.

Unpeopled Eden, in Juan Felipe Herrera’s words, takes its readers “into the gnashing river where no one really dies yet is ripped out of self.” This relationship between the idea of death and self is one of the many reasons it was named one of the best collections of 2013. Was there an element of your own self that went into any of these poems? If so, did the writing process become much more difficult?

One of my colleagues at Rutgers-Newark, Brenda Shaughnessy, once made an astute observation about writing her incredibly moving book, Our Andromeda. She said that she put so much of herself into it that the book demanded so much of her—arms, legs—that she didn’t think she was going to survive. But miraculously, she did—everything grows back. I relate to that experience because it reminds us that writing is a very physical process also, not just an intellectual one. And by that I mean that the body participates in the creative process through posture, patience and emotion.

As a writer, I put all of myself into my books, and with Unpeopled Eden it was particularly challenging because there was a deliberate purpose: to work through the grief of losing my father. This book of poetry also contained pieces that were multiple pages in length—the longest poems I’ve ever written, which required even more attention and awareness of the big picture of the poem, its expansive structure, even if I was only working on a single line or word. I knew that if I could make these long poems stand on their own two feet, I could stand on mine again. This book of poems really did take it out of me in ways that no other book had, and it was because I had to keep the pain from consuming me, from rendering me helpless and hopeless. But as Brenda said, one miraculously survives, and in no small part because the writer took control of the language of expression.

You are an English professor at Rutgers-Newark University. What is the most important piece of writing advice you give your students?

To read widely. One of my pet peeves is to mention a writer who is not obscure and yet no one in the classroom except for me has read that writer. I advise my students not to be caught off-guard. I encourage them to read their contemporaries so that they understand the community they are now part of, and to build on their personal literary ancestry. I encourage them to read poets in translation, and to share their discoveries with their cohorts so that a conversation can take place. I ask them to read across aesthetics, cultures, timelines, languages. To interpret reading text as interacting also with art, music and nature. No time is lost in reading, and much is gained by reading. I’ve learned long ago that even college students could use a mentor who is part coach and part cheerleader, who champions reading as the answer to most questions.

When I was about 11 years old, I went to the local secondhand store with my family because at the end of the shop there was a bookcase with used books that sold for a dime each. That dime was such a small price to pay that it was never denied me. I remember once standing at the bookcase, browsing, when an elderly gentleman stood next to me to browse also. He suddenly turns to me and asks, “Do you like to read?” I said yes, shyly. He nodded his head and said, “Good. Read anything. Read everything. It doesn’t matter what it is. It’ll improve your vocabulary. Here, buy yourself ten books.” And he gave me a dollar. It’s still one of my fondest memories, this moment of being acknowledged by a stranger as a reader, and then being rewarded for it with approval and a dollar. Each time I give my students books or recommend books or ask them what they’ve been reading, I remember that man whose kind gesture has stayed with me all these years.

Is there anything you want your audience to take from all your writing?

At the very least, pleasure. I hope that my writing pleases the discerning reader who places a high standard and a high value on the experience of reading. I hope that my writing opens a new window to people and places never encountered before, or that it offers a fresh glimpse to what comes across as familiar. I hope that it encourages readers to read further, certainly more of my work, but definitely more of the literature that comes from my many communities—the poetry community, the Chicano/ Latino community, the L.G.B.T. community and the immigrant community. And I sincerely hope that no matter how dire and doomed the world seems, that they find solace in the book, which is not an escape, but a different way—maybe a better way—back into that world; and [that] the world will come across a little less broken on that journey.

Is there anything you would like to add?

Yes, I’m currently working on a number of projects very dear to me: the third YA book in The Mariposa Club series, Mariposa U., will come out in November of this year and I’m currently working on another YA book, Mariquita, about an effeminate 9-year-old boy. I’m putting together a second book of essays and speeches. And I’m slowly building toward that fifth volume of poetry, which will be a book-length sequence about a historical tragedy that took place a century ago. This event and the event that inspired the title poem in Unpeopled Eden are both commemorated in Woody Guthrie songs, so I think I may dedicate my next book of poems to the songwriter/ folk singer.

Olga Segura is an assistant editor at America.