It may have been appropriate, in its own way, that the great sociologist, Robert Bellah, died on the feast of St. Ignatius. He had so many Jesuit friends, former students and colleagues at the Graduate Theological Union. Bellah was my teacher, mentor, colleague at GTU for over twenty-three years, and friend. Our lives inter-twined in so many ways. I remember, at first, when going to the University of California, Berkeley to begin my doctorate, being dissappointed that he was appointed my advisor. I had never heard of him then but had devoured all of the writings of Charles Glock, who was the main reason I chose Berkeley for doctoral studies with an emphasis on sociology of religion. It turned out, of course, that, like Bellah, my bent was for theory and the deep meaning of social structures and social change and I lacked the taste for Glock's more empirical, statistical studies in sociology (although, like Bellah and through his teaching, I did come to appreciate how to learn from them). I also learned from Bellah to look on the social sciences as moral sciences.

Others can attest to the intellectual achievements of Bellah, often enough likened to the great Max Weber for the scope and perspicacious breadth of his learning and the sway of his interests in global religion. I also had some personal and pastoral relations with Bob. When I was a doctoral student doing research in the Netherlands for my dissertation, which was published as The Evolution of Dutch Catholicism by the University of California Press in 1978, I kept sending chapters back to Bellah in 1973, who was, at that time, resident at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton. Not getting much by way of response, I began to despair that I was on the right track. I wrote an imploring and urgent letter to him. When he finally replied, he told me that he apologized but that his oldest daughter had committed suicide and he was finding it painful and shattering to adjust to that. He asked whether I knew of some good spiritual reading to help him and I suggested Images of Hope: Imagination as Healer of the Hopeless by William Lynch, S.J.

Bob and his wife of 61 years, Melanie (who was Jewish) became good friends. I recalled the other day a time when the three of us were going together to Stanford for a dinner and, then, a lecture by Peter Berger. Melanie was dawdling getting ready and Bob chided her: "Come on, Melanie, you know that sociologists and Jesuits need their scotch before dinner" and, then, in a aside to me, chuckling, he said, "especially you Jesuits!"

In 1976, a second tradegy hit Bob and Melanie. Another daughter, Abby, a senior in high school, tragically died in a brutal car accident in Berkeley. Bob asked me if I would conduct the funeral for her. "Make it as close to a kind of eucharist as you can," he said, although, of course, since Abby was never baptized it could not be a eucharist as such. For many years, Bob and I team-taught a course on social ethics and society, starting with Plato and Aristotle and going down through Aquinas. I can't remember how many doctoral comprehensive or dissertation defenses we both served together on. He always stunned me by his wide grasp of both philosophy and theology. Someone who was so widely esteemed by the likes of Jurgen Habermas, Charles Taylor and Hans Joas had to represent an exceptionally fine mind. Bob was also a very generous spirit who did not hesitate to learn from the marginal or forgotten ones of history.

One only has to read his last magisterial book, Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age (Harvard University Press, 2011), to see the scope of his learning and astute insights. I was humbled to have been invited to contribute to a festschrift honoring him, edited by his co-authors of the best-selling Habits of the Heart and The Good Society (the latter book shows Bob's interest in Catholic social teaching on the good society). I was also greatly honored to be the only outsider to the sociology department at Berkeley asked to give a testimonial speech at Bob's retirement party from the department in 1997.

Bob was a very devout Anglo-Catholic member of the Episcopal church. In mourning his passing, I went back into my journals to retrieve the homily I gave on the occasion of my last vows as a Jesuit, May 19, 1979. In it, I noted that, perhaps, the best way to understand one's particular path in life is to name one's spiritual teachers along the way. I singled out three of mine, the first of those named being Bob. Here is what I said about him, then, and I have only over the years come to see just how much my reflections captured his virtuous, kindly, generous and perspicacious humanity. I cite now from that homily at my last vows as a Jesuit:

The first teacher I lift up is not a Jesuit, not even a Catholic, although I esteem him as, perhaps, the most deeply and authentically spiritual person I have ever known. Robert Bellah taught me that Christianity is essentially a longing, an unslakeable thirst for living water in the sense of John's gospel, a profound hunger for the signs of God's presence. Bob also taught me that the holy mystery lies both veiled and yet betrayed in every human event, person, tradition and institution. He challenged me to become more truly Catholic than I have ever yet been. I know now that the only obstacle to God's deepened presense in my life is me—my complacency, my mediocrity, my too literalist expectations about where God can be found and how. Through Bob I came to be convinced that a serious outreach to other spiritual traditions besides my own is necessary if I wish to discover the meaning and validity of the Jesuit tradition for our own time. Indeed, through him I came for the first time to understand the Ignatian thrust to find God in all things—not to project him but to find him—and to seek to find him truly in all things.

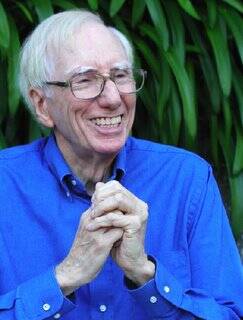

Not surprisingly, when I sent a copy of that homily to Bob, he responded: "I was quite stunned at your remarks about me which I do not feel that I at all deserve." Look at the smile of the man—he enjoyed life and was never tired of probing its wonders (and horrors) and by-ways and enticing invitations to become more fully human. Bob was never an optimist (he had too much a realist sense of evil), as he always insisted; nor was he a pessimist but a Christian and, therefore he had, despite all appearances to the contrary in our world, hope. I am sure that hope will not fail him now that he has died and is with the risen Jesus in whom he so deeply believed.