What if, instead of accusing Planned Parenthood of illegally selling baby parts, the Center for Medical Progress had just admitted up front that what was going on was legal?

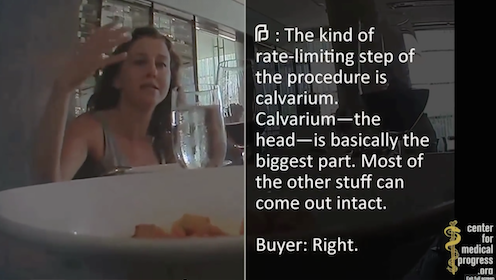

What if they had released the videos, in which a medical director for Planned Parenthood calmly explains how an abortion can be carried out to increase the likelihood of recovering the intact skull of the fetus the procedure kills, in order to recover its valuable brain tissue—and then asked us: “Right now, this is legal. Why?”

What if, instead of carefully editing out the parts where that doctor explains that Planned Parenthood can only accept payment to cover costs, and not to profit, they had left them in, and then asked if that careful adherence to legal technicalities makes any moral difference?

What if, instead of shouting #DefundPP, only to be met with #StandWithPP, we had instead been able to ask, on behalf of the unborn: “You want my brain, but why not me?”

While it has achieved new heights of political drama, the attack on Planned Parenthood mounted with these videos as the main weapon has been a tactical and strategic failure for the pro-life movement. The most recent ironic reversal, when a Texas grand jury, convened to consider whether Planned Parenthood broke the law, instead indicted the people who made the videos, provides an almost too-perfect coda to the whole mess.

As I said on the day after the first video was released, after watching the full footage, the way C.M.P. edited the videos to focus on illegal sales while obscuring Planned Parenthood’s efforts to stay within legal boundaries simply reinforced, for many people, the standard pro-choice narrative about pro-life activists as unscrupulous and dishonest extremists willing to do anything to interfere with abortion.

And now, with those very visible pro-life activists indicted for the false identification they used to get into Planned Parenthood clinics and National Abortion Federation conferences, that narrative is neatly completed.

Of course, the neatness of that story is unfair in many ways, not least in that the vindication defenders of Planned Parenthood feel should be exposed to some critical analysis. If an activist had used deception to gain access to document something that we all agreed was wrong, say for example abuse of the elderly in a nursing home or extreme cruelty to animals, would we want them prosecuted for that offense?

What if instead of focusing on how unfair it is that Planned Parenthood should emerge vindicated from the revelation that they’ve worked to maximize the collection of fetal tissue from abortions, we instead asked how we go forward from here?

I understand and share the frustration that nothing can be done to hold Planned Parenthood to account. I am still saddened and disgusted that an organization which reported 323,999 abortions and only 2,024 adoption referrals in 2014-2015 can continue to cite the meaningless statistic that abortion accounts for only three percent of the services it delivers, while probably close to one-third of its clinic revenue is derived from abortions. I remain unconvinced that government funding for other services but not abortion is a meaningful restriction, since money is fungible and the organization has made it clear that they give first priority to access to abortion.

I wish there was something we could do about it. But on the evidence of the last six months, there doesn’t seem to be a realistic path towards defunding Planned Parenthood at the federal level.

That doesn’t mean, of course, that we should do nothing. But we should do something with a better chance of changing hearts and minds and improving the national dialogue on abortion than accusing Planned Parenthood of crimes that hinge on the technical definition of "sales" and trying to drum up enough outrage to put them on the defensive.

We don’t need more outrage over abortion; we need more sadness. We don’t need anger at Planned Parenthood for breaking the law; we need weeping because what they’re doing is legal in the first place. We don’t need people shouting about baby parts; we need people asking why women are being “comforted” with the possibility that tissue from their unborn children can be used in medical research instead of being supported with the resources and policies necessary for them to feel secure in welcoming those children into the world.

We need to be asking how we can value a fetal brain more than an unborn child, and why we’re encouraging women who feel that abortion is their best or only option to do the same.

At a Mass before this year’s March for Life, just days before the Texas indictments were handed down, Paddy Gilger, S.J., preaching to students from Jesuit schools, reminded them that “No one ever changes from being yelled at. They change from being loved.”

When people we love are holding fast to great evil, we have several tasks. If we can prevent them from carrying the evil out, then we should; but whether we can or not, we don’t stop there. We have to do what we can to avoid any cooperation in or support of the wrong, but we don’t stop there either. We want their hearts to be converted; we want to help them repent of evil and choose the good.

With its video strategy, C.M.P. prioritized attacking Planned Parenthood ahead of trying to change the hearts and minds of those who support them. We’ve seen the results of that approach.

What if we try something different?

I have read the post where Kevin Clarke interviewed the Poynter Institute representative, and I agree that C.M.P.'s tactics with the videos were self-defeating, from a broader perspective of trying achieve actual change in how people view abortion. (That's what my whole post was arguing.)

With respect to the three percent number, I linked to a Planned Parenthood defender explaining why that statistic is meaningless. I don't disagree that Planned Parenthood does other things that are important and that are not abortion; I'm arguing that to pretend that abortion is a minor part of what they do is, at best, wildly disingenuous. Since Planned Parenthood (as is their right) only reports that misleading statistic and won't tell anybody how abortion relates to revenue, we have no really good way of judging the relative importance they attach to their different services.

As I said in the post, I don't think arguing to defund Planned Parenthood is the right strategic priority for the pro-life movement, but I understand why people want to achieve it. One of the reasons that's it's not the right strategic priority is because it leads into dead-end arguments like this over who really cares about women's health, instead of focusing the question on the injustice of abortion, both for women and unborn children.

Hello Crystal — thanks for commenting.

I'm not denying that Planned Parenthood provides a lot of non-abortion services. I was trying to explain (since I expect this piece will also be read by pro-life folks who may be very frustrated that I'm calling the videos a failure for the pro-life movement) that I understand why defunding Planned Parenthood seems like such an important goal. A huge part of that reason is that Planned Parenthood wraps itself in the protection of saying how important they are to women's health, which is true, and then saying that abortion is only 3 percent of what they do, which is only true is the most technical sense, and is designed to mislead. If we aren't counting every STI test and contraception prescription as a "service" numerically equivalent to an abortion, things look different. Recognizing that Planned Parenthood performs almost as many abortions as it does breast exams or Pap tests puts things in a different light (respectively: 323k, 363k, 271k according to their own annual report).

In any case, I've said above and I'll say here that defunding Planned Parenthood is unlikely to succeed and is not the right strategic goal for the pro-life movement.

Regarding responding to other comments, you've often commented about the need to focus on contraception as a way to decrease the incidence of abortion. That's a complicated and thorny issue, particularly from a Catholic perspective. It's also not been the direct topic of anything I've written about in the videos issue (since the videos don't involve contraception). The question of how much contraception can reduce the incidence of abortion certainly worthy of discussion, but I don't think it can ever serve as an answer to the question about whether abortion is unjust and wrong. We're still going to have to figure out how to talk about that.

In any case, my apologies for seeming to ignore your comments by not replying; I assure you I have read them.

If I can ask you a question in response: if pro-life folks were more willing to talk about contraception, how do you think that would change and improve the dialogue about abortion?

Thanks for replying. To push the question a bit further—do you think that convincing pro-choice people that pro-life people are more serious about reducing the number of abortions make them any more likely to give serious consideration to the question about whether abortion is unjust and wrong? Otherwise, pro-choice people telling pro-life people that they won't listen to them about abortion because they find them hypocritical on contraception seems kind of hollow. Or have I misunderstood something about how you see the issue?

About the thorniness of the contraception issue—yes, it's not just a Catholic issue. But hopefully the way I've put the question helps explain why someone with a pro-life perspective might not be convinced that talking about contraception more will necessarily advance the cause of justice they're concerned about. (And I know that's not a satisfying answer; it's not meant to be.)

Thank you for the conversation, too.

I do think the contraception issue is worthy of discussion. But I also think that work needs to be done to keep the deep question of justice alive about abortion. Certainly we should try to reduce the need for abortion, but we shouldn't "let ourselves off the hook" about the question of whether or not it is right, whether or not it sacrifices the innocent lives of the unborn, and whether or not it contributes to structures that expect women to choose between pregnancy and economic security/opportunitity.

And quite often, I think that the shift to "how do we reduce the need" is a (sometimes only implicit) way to move away from the question of "is this just?" and "why is this legal?" We need to find ways to talk about those questions in common, and I don't think focusing on contraception, as important as it is in other ways, helps us there.