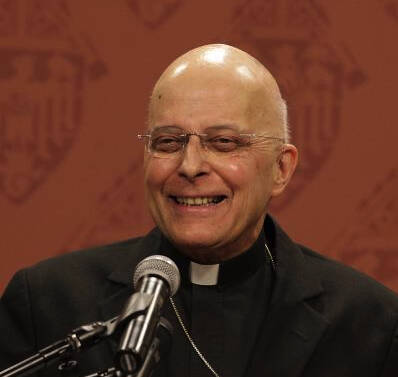

Cardinal Francis George, O.M.I., of Chicago gives up pastoral governance of the Archdiocese of Chicago on Nov. 18, when Archbishop Blase Cupich becomes Chicago’s next episcopal leader. Here is an e-mail Q&A that Cardinal George, a member of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate (O.M.I.) granted to America. In it he discusses struggles with life-threatening cancer and the after effects of childhood polio; the role of an archbishop, the recent Synod of Bishops on the Family, the handling of sexual abuse by clerics, celibacy, liturgical translations and other church issues.

1. As a person of faith, from your own experience of age and illness what hope and consolation do you find yourself bringing to others?

Many people are living with chronic and life-threatening illnesses, especially various forms of cancer. I remember often the advice given me, when I was thirteen and had contracted polio, by a neighbor whose daughter began her experience with the disease a year before. He came to my house, ran my leg through some exercises and said that I was not as severely affected as his daughter. Then he told me: “There is always someone who is worse off than you. Don’t ever feel sorry for yourself.” I have recalled this advice many times, in different circumstances over the years. It was the best advice I ever received. It enables me to encourage others, and many now write to tell me that they have found courage to face their own illness because I am still doing, in an increasingly restricted way, what I have been called upon to do by my office. At the same time, God also purifies us, and I have a sense that I’m being taught to let go, to put aside many of the concerns that have shaped my life, even as a bishop. I welcome that “purification of desires,” because it brings the “Unum necessarium” into clearer focus.

2. What would you advise your successor is the most important issues he will face as archbishop, a probable cardinal and as a member of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB)?

A bishop stands for Christ, the head of the church. What he faces is always tied to that vocational understanding. It means that the bishop has a unique perspective on the “whole,” on an entire local church with all its people, its ministries, etc. His challenge is to keep everyone focused on the mission, the purpose of the church and not let people get distracted by ministries, by what they have to do. His is a ministry of unity. Within that vision, he has to see that the church has the institutions necessary to pass on the faith and that the faith is clearly enough presented to call people to conversion of life. He has a special relationship to the priests and to religious men and women, deacons, lay ministers and others who have dedicated their time and sometimes their entire life to the mission of the church. He has to see that the poor and all others are part of the church’s sense of unity, as actors and not just aid recipients. He has to see that the basic liturgical discipline of the sacramental life of the church is respected, because the sacraments are the actions of the risen Christ. They are not just ecclesiastical rites. All of this has its financial dimension, and the bishop must help to engage people’s generosity. A growing challenge to this “normal” life of the church and the full range of a bishop’s concerns is the secularization of our culture and the conviction, on the part of many, that religion is a threat to peace and social harmony, not a contribution to the common good.

3. Do you agree that the bishops have been more politically active in recent years and what do you consider the successes/weaknesses in their activity?

Since the common good is expressed in this country by law, the bishops have always addressed changes in our legal system that would undermine the biblical anthropology that our doctrines presuppose. In other words, we are no longer a biblical people, and the law sees only individuals and their rights instead of persons and their relationships. I don’t believe the bishops have been more politically active in recent years, but it is true that our political activity is more adversarial as the law no long permits the “exceptions” that used to safeguard believers whose conscience will not permit them to approve of what has become lawful. The “price of citizenship” is high when it means one must approve as human rights the killing of the unborn, the creation of false marriages between two men or two women, the universal availability of free contraceptives, especially for women from a very young age. The Gospel is a message of freedom, and the Catholic way of life trains people in habits that protect that freedom from slavery to various addictions, etc. My own conviction is that we must be completely clear about the Gospel and how it is to change us, and then we work respectfully with individuals and groups who cannot agree with us. I do not know that we will be permitted to have that pastoral approach in the immediate future. We will not be permitted to enter into the public conversation unless we approve of what our faith knows to be morally wrong.

4. As the bishop who led the American side of the mixed commission that got the sex abuse norms approved in 2002, how do you evaluate how the bishops have done in implementing them?

I think the bishops have done well in understanding that zero tolerance, which was very difficult for Rome to accept ten years ago, is the basis of our ensuring that children will be safe and that the moral credibility of the church will be restored. Some have done less well in setting up the procedures and the systems needed to determine whether or not a priest or a deacon is truly guilty of having abused a minor child. Some allegations and their surrounding stories are complex, and the civil authorities are not always helpful. I think most bishops have done well in reaching out to victims and giving them the pastoral care necessary to restore their trust and rebuild their life. Because of our tort system, the costs of helping victims are very high and, consequently, some dioceses have gone into bankruptcy. Most dioceses, I believe, have good prevention programs in place. There are very few accusations against a priest who has not previously abused a child; the newly reported instances of abuse are mostly historical. There are both individuals and groups, however, who do not want this tragic saga to disappear from the headlines; they have a vested interest, whether financial or ideological, in discrediting the church.

5. Many church leaders have expressed in recent years (perhaps you among them?) the opinion that a smaller more unified church might be better. Now Pope Francis seems once again to be encouraging people of diverse views to be part of the Church. What do you think of his approach?

I don’t know any bishop who has said that he believes a “smaller, more unified” Church might be better. What I have heard Pope Benedict say is what Karl Rahner once expressed: it will be so difficult to be a Christian that the church will be composed of mystics and others similarly committed. But this is not represented as an ideal to be hoped for. Christ died to save the entire world. The church’s job is to share Christ’s gifts as widely as possible, among all peoples and nations, without exception. No believer wants the grace gained for everyone by Christ’s death and resurrection to be wasted or ineffective. Within a universal church, there will be not only sinners (all of us) but also those whose commitment varies from time to time and place to place. The parables of the kingdom speak of a church filled with wheat and weeds, not a field purged of anyone who does not understand or accept all the demands of the faith. Recent popes have done their best to motivate Catholics to support missionary activity and to enter into the New Evangelization—calling everyone into Christ’s body, the church.

6. Pope Francis may be the first pope who as a pastoral leader was faced with the kind of desperate poverty that is no longer experienced in this country. Is there a communications gap between his experience of how economies operate and those in this country who tend to view the operation of our economy uncritically?

There is a gap between any Pope and those who would accept our economic system uncritically. The major criticisms of any economic theory are in Catholic Social Teaching: the universal destination of all material goods, the treatment of the poor as the gage of a just economic system, the need for some regulation of markets so that return on capital does not completely outrun gains from wages, the social mortgage of private property, etc. Both Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict contributed to rather sophisticated advances in the church’s teaching on economic order. They were able to address the technical challenges of supply-side economics, the production of wealth so that more wealth can be distributed, the creation of an economic order founded on “gift.” Pope Francis, so far, with the poor uniquely at the center of his concerns, has focused on distribution. This is a common criticism of religious leaders: they understand distribution but not production. As challenges to an economic system that is still far from what the Gospel would encourage us to work for, Pope Francis’ statements ring true; as judgments on economic theory as such, a lot more has to be said. The Pope speaks, it seems, from the experience and the analysis of South Americans who believe that some are rich because others are deliberately kept poor, that the “system of neo-liberalism” captures capitalism in its entirety. It remains true that no Catholic can view the operation of our economy uncritically.

7. Reconsideration of celibacy of the priesthood in the Latin Church seems for the first time to be a possibility. Do you agree that it is only a discipline open to change or does it have doctrinal implications?

Celibacy for the sake of God’s kingdom is a Gospel value. The Latin church chooses as candidates for ordination to priesthood only from among those who can also say they have been called to celibacy. Since the priest represents Christ as head of the church, it is most fitting that the priest have as bride only Christ’s own bride: the church. The “discipline” goes back to the end of the Roman persecutions. Even in the Eastern churches, the bishop must always be celibate. The relation between Christ and the church is spousal, and, consequently, so is the relationship between the ordained priest and the church. In a post-Freudian culture, celibacy is an object of hatred; hence its witness is more important than ever. It reminds people of the total self-surrender that is the heart of Gospel radicalism. This is not, therefore, the time to change the “discipline” here. The anger that gathers around this question, and the ordination of women, the indissolubility of marriage, the definition of marriage, etc. bears witness to how a corrupt culture forms its devotees. They are also class issues—these are not the issues at the center of poor people’s concerns. These are the concerns of those who are most identified with current cultural “trends,” those who have “made it” and believe the whole world should think like them. At the same time, we have to meet all people where they are and consequently search for ways to explain and present the Gospel in all cultures, including our own.

8. You were prominent in the work of theInternational Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) and the development of the new liturgical translations. Now that they have been in use for nearly two years, are you satisfied with the translations pastorally and theologically?

It’s hard for me to give an unbiased judgment on the value of the new translations. First of all, the first full translation of the missal of Paul VI was ideologically charged. Since the liturgy, along with Sacred Scripture, is the primary carrier of the tradition that unites us to Christ, the loss of the theology of grace, the domestication of God, the paraphrasing that deliberately omitted nuances of understanding, the deliberate omission of biblical references in the liturgical text itself, etc. left the church for forty years without a way of worship that adequately expressed our faith. This was clear for those of us who used the Roman missal in Spanish during those years; their translation was far more adequate. The bishops had the obligation to see that the translation into English of the third edition of the Roman Missal was faithful and also able to be used communally. I believe it has been well done. Some of the expressions in the Prefaces are a bit “clunky,” but the collects are truly beautiful if a priest takes the time to interiorize the structure of dependent clauses and use his voice so that the prayer is comprehensible to the faithful. Normally, people paid little attention to the collect; they couldn’t tell you what the priest said as soon as they sat down. Hopefully, a more deliberate style of declamation with a more adequate text will help draw people into a climate of worship and prepare them to hear the Word of God in Scripture. The canons are very well done, even the most difficult, Canon One, because it is a compilation from various sources. Criticism of the scientific inaccuracy of the word “dewfall” in Canon II is a bit absurd coming from those who easily accept and speak of “sunset.” Some of the criticisms have an extrinsic rationale. The bishops’ choice of experts meant that many who had been more involved in the work of ICEL previously were no longer engaged. The loss of a work to which one had given oneself is always hurtful. Some others just opposed any exercise of episcopal authority; in principle, the bishops were just supposed to rubber-stamp what the “experts” were doing. Some, surprisingly, objected to the re-introduction of the biblical metaphors and allusions, while others underestimated, I believe, the native intelligence of the average English-speaking worshiper. There were a few more justified criticisms of the process, which was open in places to accusations of last-minute manipulation. I have to say that I enjoyed going back and working through Latin texts, something I hadn’t done since minor seminary.

9. The issue of Catholics who are divorced and remarry without an annulment looks like it will come up at the forthcoming Extraordinary Synod of Bishops. Do you have suggestions on how to address the issue of Catholics who have remarried without receiving an annulment of the first marriage as well as suggestions on changing the annulment process?

I think we have to listen carefully to what is reported about the discussions in the Synod. The process of judging the sacramentality of a marriage is one that should be thoroughly re-thought; but it has to remain a process outside of the forum of conscience alone. No one is a judge in his own case, as the proverb has it. Self-delusion is a danger that has to be addressed in the forum of courts or their equivalent. I have heard many good suggestions about how to improve the present system of granting annulments. I hope they will be acted on. Pastoral practice, of course, must also reflect doctrinal conviction. It is not “merciful” to tell people lies, as if the church had authority to give anyone permission to ignore God’s law. If the parties to a sacramental marriage are both alive, then what Christ did in uniting them cannot be undone, unless a bishop thinks he is Lord of the universe. The difficulty of giving communion to parties in a non-sacramental marriage doesn’t stem from their having sinned by entering into a non-sacramental union. Like any sin, that can be forgiven. The difficulty comes from avoiding the consequences of living in such a union. It is foolish to believe that a publicly approved although “restricted” exception to the “discipline” around the sacrament will remain “restricted” very long. When speaking of acting “pastorally,” a bishop has to ask what is good for the entire church, not just what might be helpful to an individual couple. How the entire pastoral conversation around marriage will change with a change of “discipline” is a question that must be answered before making any other decision.

10. Are there other contemporary issues you want to address?

Give me a chance to think!

Mary Ann Walsh, R.S.M., is a member of the Northeast Community of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas and the U.S. Church Correspondent for America Magazine.