In mid-February, a group of Chattanooga workers voted in what conservative commentator George Will called “the most important election of 2014.” They were workers in the Volkswagen plant, choosing whether or not to form a union.

Will was not exaggerating about the vote’s importance. For America’s working men and women, union membership usually has more impact on their lives than which party controls the House or Senate. A hotel housekeeper or building janitor typically earns a living wage if they belong to a union, and a poverty wage if they do not. Union contracts generally include employer-paid health insurance, so their health care does not depend on the fate of the Affordable Care Act. In mid-term Congressional elections like the one coming up in November, about 40% of eligible voters turn out; nearly 90% of eligible workers in the Volkswagen plant participated.

When those votes were counted, 626 workers had voted to join the United Autoworkers—but 712 voted against. The result is disturbing for union advocates, because this was about as close to a level playing field as you are likely to see in a union vote.

Under the National Labor Relations Act, workers generally choose whether or not they want to form a union through an election campaign in their workplace, one that pits union supporters against union opponents. Ordinarily, employers threaten, discipline or fire union activists, making organizing extremely difficult. In more unusual cases, employers adopt a neutral position, and the advantage—though less pronounced—shifts to union supporters. Will and other anti-union commentators fantasize that rampant “intimidation” by union organizers explains this. That’s nonsense, but when the company is in fact a disinterested party, union supporters enjoy the assistance of a well-resourced and experienced team of union organizers to help make their case, while skeptics are left to their own devices.

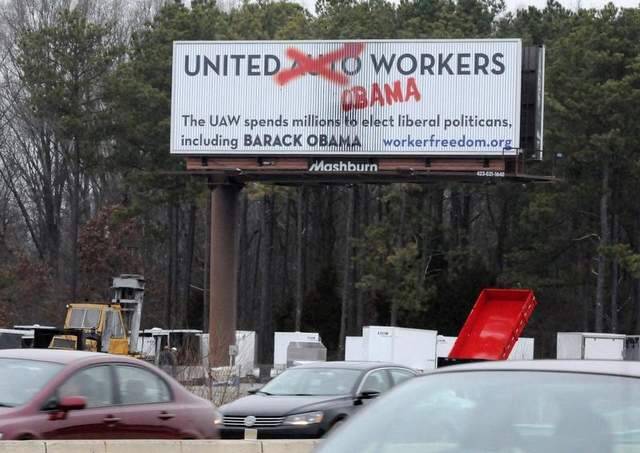

In this case, workers on both sides felt safe making their case openly, and both groups enjoyed professional backing: UAW supporters from union organizers, opponents from a variety of conservative organizations (like Grover Norquist’s “Center for Worker Freedom”) who parachuted in to assist the “no” campaign. And by a 53%-47% margin, workers opted against the UAW and collective bargaining.

To join a union is to form an association in the workplace. It’s a democratic association, one where workers elect their leaders and engage together in collective bargaining, but like all associations it carries a price—one who chooses association assumes duties as well as rights. In the end, individual liberty proved more compelling than solidarity for the majority of the voters, and that bodes ill for organized labor.

“Solidarity is undoubtedly a Christian virtue,” as John Paul II observed. But with each passing day it seems less and less an American virtue.