Addressing the Catholic Finance Association in New York City: October 7, 2014.

I am happy to come to this conversation not only as a Jesuit priest, but also as a proud graduate of the Wharton School of Business. To establish some bona fides, I was a finance major at Wharton, took a job in the Financial Management Program at General Electric in New York City, which was then the International Finance and Accounting headquarters of GE, worked after my training program for a year in international accounting, and then took a job running the FMP program at GE Capital in Stamford, Connecticut, and finally moved into human resources. So I come before you as someone who knows that business is a real vocation, who still has many friends in business (and specifically in finance) and who also knows that business is a real way to contribute to the common good.

So I approach our discussion of executive compensation from a financial point of view and a human resource point of view, but also, of course, from a Catholic point of view. You will hear a lot about the financial perspective and the human resource perspective tonight from our other distinguished participants, but I think what I might be able to contribute is the Catholic perspective.

The Catholic perspective on salaries, compensation and labor is the Christian perspective in general, and the basis of that is always the Gospels. You all know what Jesus commands us in the Gospels, and, we might say even more accurately, invites us to: Love our neighbor. Pray for those who persecute you. Forgive someone seventy times seven times. And of course care for the poor. Jesus is born into a poor family in a poor town, he works as a carpenter, which at the time would've been seen as a very low-class occupation (below the peasantry, since the carpenter did not have the benefit of a stable plot of land), he sees the disparities between the rich and poor in his own lifetime, and he constantly pointed us to the poor and the marginalized in his public ministry. So this is the Christian perspective.

But Catholic teaching, and specifically Catholic Social Teaching, has a great deal to say about economic conditions in general, and this teaching builds on the Gospels and, as embodied in the great papal encyclicals, enjoys the highest teaching authority in the church.

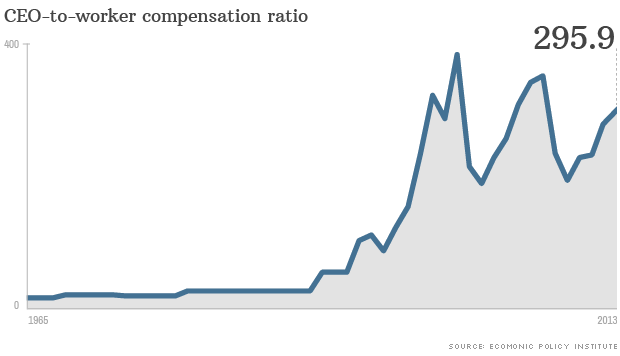

Now, just to tip my hand, I believe that capitalism is the most efficient economic system in distributing goods and services to people. But it's also not perfect. How do we know that it's not perfect? Because we can step outside today and probably after just walking a few feet, meet a homeless person begging for food. We can also see gross disparities in living conditions around the world and in this country, and even, given what we are talking about here, gross disparities in executive compensation compared to what the average worker makes. As you may know, CEOs in the United States make something like 300 times as much as the average worker, and 700 times that of the minimum-wage earner. That statistic comes from Forbes magazine, by the way.

Catholic Social Teaching has focused more on the issue of minimum wages than anything about the upper end of the pay scale. There is, as far as I know, nothing explicit about CEO pay in the major Catholic social teaching documents, that is, about maximum wages. Nonetheless, one can easily extend the logic of Catholic Social Teaching to address of the thinking of our church’s social teaching to what I would call excessive maximum wages, which effectively crowd out the ability to provide a decent minimum wage for the lower wage workers.

In other words, we need to remind ourselves that the dollar slipped into the pocket of the CEO come out of the pockets of the person in the factory. Money in the corporation is finite. A corporation makes a certain amount of profits per year. CEOs and boards, when they are deciding on CEO pay are, in essence, then, allocating dollars.

Fairness, equity, and solidarity are constant themes in Pope Paul VI's great encyclical Populorum Progressio. Pope Paul, who was hardly a liberal nutcase, decried the situation where "misery and luxury rub shoulders" which suggests a great level of discomfort with the extremes of the rich and poor. Other encyclicals have repeated the church's opposition to such great levels of disparity in income. After all, the low-wage worker often works much harder than the high-wage earner, and often in far worse working conditions. Jesus, the humble carpenter from Nazareth, would have known that.

In fact some Catholic theologians today are positing not just a "minimum wage," but even "maximum wages."

So the question I would ask Catholics and Catholic CEOs is quite blunt: What do you want to say to Jesus when you reach the gates of heaven? Do you want to say that you took as much as you can, even as much as the market would bear, because your board okayed it? Or do you want to say you accepted what you thought was just, and understood the needs of your fellow men and women, who may have worked even harder than you?