It was on this day in 1990—February 11—that a man of great dignity and bearing emerged from many years of captivity into the sunlight of freedom. It was a long time coming, this “freedom”; as he had spent the large part of his life—27 years—in a narrow, cramped prison cell. Eighteen of those years were spent in the same place, on a remote island, where he was forced to work along with others in a lime quarry. They were difficult years—years that could easily make or break a human being. He was imprisoned for all that time because of what he was and who he was: a black man. He was imprisoned too, for what he believed as a black man: that he had rights and responsibilities equal to everyone else; only the people who imprisoned him refused to believe that.

And in that time, while his health suffered, his spirit did not. The reason for that was as simple as it was complex: for he was, as the phrase goes, “interiorly free.” Having been forced to work along with others in a lime quarry, his eyesight was negatively affected. It deteriorated from having to endure the sun glare reflecting from the quarry itself. (His prison guards would refuse him the protection of sunglasses.) And having had to inhabit a narrow and dank cell, he would later on suffer from tuberculosis. It was a struggle for his body to survive; but only did so because of the determination of his will and his spirit, which would not permit him to surrender to the hate which apartheid had imposed and imprisoned him.

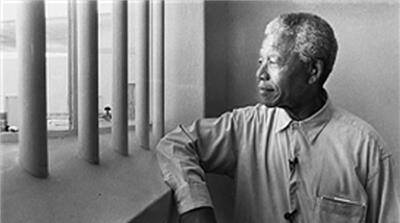

It was his spirit that enabled Nelson Mandela to survive. It was his spirit that enabled him to prosper amid such inhumane conditions of the dank cell, the enforced solitude, the primitive living arrangements of a patted straw mat to sleep on, a metal cup and plate from which to subsist on and the use of an ordinary pail that served as his toilet and the limited human contact he had through sparse letters and even more sparse human visitations. His only connection to the outside world, to the freedom he had once known, was the wide prison barred window that allowed him to look out to the sun and to the sea and to the life beyond.

In those years, his spirit became his teacher: the extroverted man became not an introverted man, but an “interior” man, in that he came to terms with himself, his humanity and the humanity of his fellows, even of those who hated him. The spirit that was his soul imparted lessons that became a part of him, never to be erased, but firmly implanted in him.

In time, his living conditions would improve and his health would be looked after; but he would still be physically imprisoned. Not for long would he be; people from beyond that prison window would take up his cause and fight for his release, despite the tremendous opposition from the people who possessed power, those who were not his own and those who refused to understand him or his purpose.

Eventually, he would be released and eventually, he would become the president of his country and preside over a reconciliation he desired, not just for his own people but for also for those who had the power and privilege and who denied it for so many years from people like him. He would become a “player” on the world stage and he would meet with popes and presidents amid great acclaim. Despite the trials and tribulations of his life, he acted with grace and dignity that befitted his humanity. When he died—at the age of 95—after a quiet retirement, the world reflected upon the momentous achievement of a man once a prisoner who became president and they mourned him. He was proud of who he was, but he did not let that pride get the better of him. He knew who he was and what he was meant to be: a free human being.

He looked out that window of Robben Island many, many times. And when he looked out, he recognized a truth that is applicable to us all, whatever we are, whomever we are, wherever we live. This truth he recounted in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom: “No one is born hating another person because of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

“I went on a long holiday for 27 years,” said he, of his prison years in South Africa.

The most important lesson Nelson Mandela learned in his long life was also his most important legacy: it was the one he learned by looking out of the window of his soul.