A lot of us are sorting through our Daniel Berrigan memories this weekend. Many, surely, knew him or of him when he was young and stirring up heaps of trouble. I only knew him when he was old, so weak that the poetry of his sharp tounge remained mostly under his breath.

There are a bunch of things—his way of saying Mass in ordinary, scandalous words, his gentle asking after whatever I was writing. I knew that when the day of his death came, I would regret not recording those utterances better. But one moment I did happen to record, in my book "Thank You, Anarchy," was the day Dan came to Occupy Wall Street—October 5, 2011.

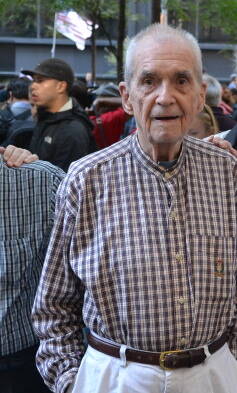

Just when you think it’s over, there is so much further to go. Back on October 5, a few minutes before the big march to Foley Square began, I ran into Daniel Berrigan and some of his fellow elder Jesuit priests at Liberty Square, all in plainclothes. This was a wonderful surprise. The plaza was overflowing with new faces that day, and I was happy to see some familiar ones. I generally have dinner with Dan and the others once a month, and I felt that I could stand a little taller than I ever had around them before because now my generation had its movement, too.After I cajoled the Jesuits into posing for a picture with me, we were approached by a man who introduced himself as a TV reporter from Greece. He had a cameraman waiting a few paces behind him. I nodded a hello, but he went straight for Dan.“Can I interview you?” he asked. “I’d like to show the world that it isn’t just a bunch of radicals here.”What he was referring to, of course, was the widespread perception that this occupation was a mob of mischief-making kids, and surely an old man would prove otherwise. The reporter had no idea whom he was talking to, that this old man was possibly the most radical person on the whole plaza. Dan, ninety years old at the time, had spent a lifetime in resistance against war and empire. For his trouble, he served years in prison—not just a few hours in a holding cell.Sacrifices were only starting to be made, and the powers that be had only begun to feel the least bit threatened, if they did at all. The protomovement still could have faded away with little harm done. To me, and to most of the young people there who were doing this for more or less the first time, these had been among the longest, best, and most sleep-deprived two-and-a-half weeks of our lives. But seeing Dan there put those weeks in perspective. They were just a practice.