When we meditate, each person follows his or her inspiration. I use a variation of the Jesus prayer, repeating a mantra again and again. Of the various mantras, the one I like best is “Lord Jesus, have mercy on me a sinner.” I like to be clear that I am a sinner. This does not cause me guilt because I know that Jesus loves sinners. Often I have recommended this kind of meditation to the participants in my group. Many of them say in Japanese, “Jesus, have mercy on me” and repeat it again and again, not only when they are in the lotus before the Blessed Sacrament but while they are sitting in the train or washing the dishes.

I was inspired to pray this prayer by reading The Way of the Pilgrim, the little book of the Orthodox monk who walked around Russia repeating “Lord Jesus, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.” He was putting into practice the exhortation of St. Paul to pray without ceasing: “Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances” (1 Thes 5:17). The pilgrim (as he called himself), taking Paul literally, walked around Russia filled with joy, reciting the name of Jesus and always giving thanks.

This way of meditation suits the Japanese because recitation of a mantra is in their tradition. Some Buddhists use the mantra Namu Amida Butsu, calling on the Buddha Amida for mercy; in another Buddhist sect the participants say Namu yo Horen Gekkyo, reciting the Buddhist love for the lotus sutra. To call on the name of Jesus continually makes sense to the Japanese. Many do pray without ceasing, continuing their mantra after their formal prayer. I believe that Buddhism is deep in the mind, heart and body of the Japanese, even in those who do not belong explicitly to any Buddhist sect. For this reason some people quickly come to understand St. Paul’s words, “I live, now not I, but Christ lives in me” (Gal 2:19), for they experience Jesus dwelling in the depths of their being.

From the Little Ego to the Big Self

In this kind of meditation we can go down through our unconscious mind from the little ego to the big self. Thanks to Freud and Jung and the psychological theories of the 20th and 21st centuries, we recognize that there are many layers in the mind, through which we can go down, down to the very depths of ourselves. Some people do this in counseling, others in meditation. Still others, like me, use a combination of both. Deeper than the self, or somehow within it, I come to meet the great mystery of mysteries we Christians call God and believers of other religions call by different names.

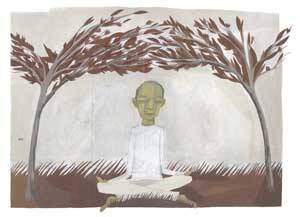

Perhaps I can describe the process of meditation with a crude diagram:

Top level of consciousness

Unconscious

Silence

True Self

God

In meditation over the years, I have moved down through many levels of silence. This entailed much agony as I passed through the painful night of the senses, but it also brought much joy and gave me great creativity. Whether I reached the dark night of the soul, I do not know. I have read St. John of the Cross extensively and have studied the 14th-century English mystic who wrote The Cloud of Unknowing, trying to become detached from all things by entering the cloud of forgetting. I think I found some experience of the true self, but I have not experienced God except through faith. I believe that God is the mystery of mysteries and that when we meet God we can only say that we experience Nothing or Emptiness.

Over time, my prayer passed from repeating a mantra to absolute silence with only the sense of presence. I became increasingly interested in the mysticism of Asia. I was a close friend of Enomiya Lassalle, S.J., a world-renowned Zen master; and I went to India, where I stayed in the ashram of Bede Griffiths, a Benedictine monk (some would say a spiritual master) living in India who wrote on mysticism. From Bede, and from his books and conversations, I learned about Sri Ramakrishna, the Indian sage (1836-86); I also read about Gopi Krishna’s experience of kundalini, a breakthrough that occurred first during meditation and later became a state of being, which gave him a different perspective on the world, a new vision of the universe.

Together in the Darkness

This was a time when the interreligious dialogue encouraged by the Second Vatican Council was becoming popular, and I began to ask myself if we, believers of all religions, were together in the silence, the darkness, the emptiness, the nothingness and the cloud of unknowing. If we were, we could say that all religions were both the same and different. They were the same in the silence at the peak of mysticism; they were different in their verbal devotions. In Assisi in 1985, the representatives of all religions bowed in silence with Pope John Paul II and then went to different corners of the city to pray with words, using the Koran or the Bible or the Sutras or whatever devotional literature was in their tradition. Can we finally say, I wondered, that there is one religion with many expressions, and that we must work together for peace in the human race?

This problem preoccupied me for a long time. I once consulted the Japanese Catholic priest Oshida Naruhito about doing Zen. He said, “Go ahead if you like, but I think you will find that they [Buddhists] have a different faith.” Oshida himself practiced much sitting in the lotus position at his little ashram on the mountain where he is now buried, and he gave many retreats in which the participants sat in the lotus position for hours and hours. But he never said that he did Zen. I took him to mean that the silence or nothingness was in fact penetrated by whatever faith the participant embraced. Perhaps he was trying to say that in the silence of Zen there is an underlying something that is different from what underlies Christianity.

The advice of Father Oshida was good for me. I did a little Zen, but not much. I found that I did not want to remain always in the absolute silence of nothingness. I wanted sometimes to return to my “Jesus prayer,” and I liked to sit before the tabernacle that contained the Eucharist.

But I did find—and still find—that the silence of mysticism is our best meeting point as followers of different religions. It is here that we can be united; it is here that we can meditate together. Many years ago I joined a group of Buddhists and Christians who meditated together in the shrine city of Kamakura outside Tokyo. We all sat in silence, so what the others were doing interiorly I do not know. But I do know that we became good friends, and that made it an excellent dialogue. I believe that mystical silence is the best meeting place for the great religions.

My religious superior at that time was the deeply spiritual Jesuit Pedro Arrupe. In a yearly interview with him I spoke of my interest in the mysticism of the East and West, and Arrupe said with a smile, “I don’t think St. John of the Cross will satisfy you.” This was a surprise to me, but now I see the wisdom of his comment. He meant that as a Jesuit I was called to contemplation in action, and that pure Carmelite contemplation was not my cup of tea. Moreover, as I read the Scriptures, I began to gain new insights into St. Paul. That great apostle wrote regarding faith, hope and love that “the greatest of these is love” (1 Cor 13:13), and Paul’s mysticism is a wonderful love song. But after love come the spiritual gifts, less important than love, but very valuable. For an active person like myself I saw—and I think Arrupe saw—that these gifts were necessary.

Paul puts great emphasis on the gift of prophecy, encouraging us to “pursue love and strive for the spiritual gifts, and especially that you may prophesy” and reminding us that “those who prophesy speak for other people for their upbuilding and encouragement and consolation” (1 Cor 14: 3). I began to wonder if our little meditation group is called to prophecy. Is this the vocation of those who meditate in our day?

Am so glad to have found (or re-found) William Johnston. I must have gotten his book, "Mystical Theology", many years ago. Today, I found it sitting upside down on the back of my desk. I think that Jose, who helps me clean, must have found it under the bed or something and put it back there. I had forgotten about it. I opened it up and there was a photo of me and Dan Berrigan, walking the beach. The photo was from the mid-1990s. I looked at the book, astonished that it would just show up like that. Then I read the back cover, about how the contemplative state of consciousness is really the state of "being in love with God". I am now reading the book slowly, as if for the first time. I have a new teacher: William Johnston. Funny how these things happen. I also think that Dan Berrigan is somehow involved.