ISIS-sponsored and -inspired terror attacks have left Americans fearful of their personal safety at percentages not seen since the 9/11 attacks. The terror strikes and political rhetoric emerging from a heated race among a number of contenders in the Republican presidential race have brought sometimes hostile focus on the nation’s large Muslim community. An analysis sponsored by the New York Times found that hate crimes against Muslim Americans and mosques across the United States have tripled since the attacks in Paris and San Bernardino, Calif., with dozens occurring since mid-November.

The Times reports: “The spike includes assaults on hijab-wearing students; arsons and vandalism at mosques; and shootings and death threats at Islamic-owned businesses.”

Turning up the heat during a stressful time, GOP candidate Donald Trump called for a complete ban on people of the Muslim faith who are not U.S. citizens from entering the country. While the proposal was roundly condemned by civil libertarians and leading figures from both the Democratic and Republican parties—condemned indeed even among the people campaigning alongside Trump for the Republican nomination—Trump’s call to close the borders to Muslims was not rejected by the people who may matter the most—the Republican electorate who will be choosing their party’s presidential nominee for 2016. In a recent Washington Post/ABC news poll, 60 percent of Americans overall say Trump’s proposed ban on Muslims “is the wrong thing to do,” but the survey also found that among Republican voters Trump’s ban was supported by 59 percent.

Political rhetoric which has the effect of fanning anti-Muslim sentiment was roundly deplored by leaders of the U.S. Catholic Church following Trump’s statements and San Bernardino, an act of apparently home-grown terror planned and executed by a Muslim-American and his Pakistan-born wife. Without specifically noting Mr. Trump’s proposal, Louisville’s Archbishop Joseph Kurtz, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, said in an Advent message, “We have reason to announce the need for peace and goodwill throughout the world with even stronger voices this year, in light of the recent mass shooting in San Bernardino. Violence and hate in the world around us must be met with resolve and courage.

“The Christmas story,” he said, “inspires us to give of ourselves, as Jesus gave up his body, so we may bring comfort and joy to those in need. We must not respond in fear. We are called to be heralds of hope and prophetic voices against senseless violence, a violence which can never be justified by invoking the name of God.”

The archbishop urged U.S. Catholics to “resist the hatred and suspicion that leads to policies of discrimination.” Instead, he called for Americans to channel emotions of concern and protection “into a vibrant witness to the dignity of every person.”

“We should employ immigration laws that are humane and keep us safe,” he said, “but should never target specific classes of persons based on religion.

“When we fail to see the difference between our enemies and people of good will, we lose a part of who we are as people of faith. Policies of fear and inflammatory rhetoric will only offer extremists fertile soil and pave the way toward a divisive, fearful future.”

In Detroit, Archbishop Allen Vigneron did not use Donald Trump’s name, but he rejected a border control policy that would specifically bar Muslims, saying the idea “fractures the very foundation of morality on which we stand.”

Vigneron’s denunciation was included in a letter he sent on Dec. 10 to his priests and to Muslim imams in his state. He noted that the U.S. Catholic Church would not weigh in “for or against individual candidates for a particular political office.” But the church “does and should speak to the morality of this important and far-reaching issue of religious liberty,” Vigneron wrote.

“Especially as our political discourse addresses the very real concerns about the security of our country, our families, and our values, we need to remember that religious rights are a cornerstone of these values,” he said. “Restricting or sacrificing these religious rights and liberties out of fear—instead of defending them and protecting them in the name of mutual respect and justice—is a rationalization which fractures the very foundation of morality on which we stand.”

Baltimore auxiliary Bishop Denis Madden has had long experience working with people of different faith backgrounds, but particularly with Muslim people from all over the world. Bishop Madden is a member of the Bishops Committee for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs and its former chair. He has served as Associate Secretary General of the Catholic Near East Welfare Association and previous to that was the Director of the Pontifical Mission for Palestine office in Jerusalem.

He called on U.S. Catholics to join Pope Francis during this Jubilee of Mercy in seeking reconciliation with people of other faiths. Is there a positive way to respond to acts of terror that perplex and frighten so many? Bishop Madden encourages Americans “to step back and to not fall into that trap of making these gross generalizations.

“We could do that any way we want," he suggests. "You could say, ’All Catholics’ or ‘All Irish,’ ‘All Italians.’ … I think that to be able to say, ‘Yes this is a distinct group of people, who are violent, who are extremist, who are doing barbaric things,’ and not to shy away from [that judgment], but not to paint a whole society, a whole group, a whole religion, a whole faith, to condemn them as being responsible for these things.

“I think that it’s important to realize that they do not represent the majority, that they do represent a select group of people.”

During the 19th century, Catholics coming to the United States faced a great deal of overt hostility and even acts of violence from “nativists” who hoped to keep America Rome-free. Bishop Madden thinks the overt hostility many Muslims face today may even be a little bit worse than that. “They’re really viewed in a sense as terrorists; [there’s] almost a sense that you can’t really turn your back on them… there we will always be at risk with them.” The bishop remembers he experienced a bit of that kind of hostility during the worst of the sex abuse crisis, when, because of the deplorable acts of a minority of priests, he was treated as suspect wherever he went by virtue of his Roman collar. U.S. Muslims, he worries, face far worse now when they are out in public because of their sometimes distinctive dress. “That’s a terrible feeling to have,” he says. “No one wants to feel that way.”

Within the Muslim community, he said, “like all communities and all groups, you have people at all ends of the spectrum. Some are very, very good and inspiring people and some are not so inspiring, but one of the things I learned especially when working in the refugee camps were a lot of the qualities of [Muslim] people. One of the big ones that stands out in my mind is the quality of their hospitality, and this idea of the guest, the place of the guest.” That emphasis, he said, did not reflect an artificial attention to a cultural practice but “a sincere part of what their life was like.”

In his work among Palestinian refugees in Gaza and Lebanon, he also noted the appeal Islamic extremism held out for hopeless and disenfranchised youth. Pointing out how rejected, how forgotten such youth were by Western political and social leaders was a rhetorical opening often put to work on such young people by extremists recruiters, he said.

“When someone makes a statement like [Trump’s], anyone at all, let alone someone who is seeking the highest office in the country, at best you could say this is a knee-jerk response," Bishop Madden says. "I don't think it is; I think that it's worse than that.” It can be another recruiting opportunity for “lost souls,” he says, persuaded to take the path of a violent martyrdom. “To make a kind of statement, even if you were seriously trying to protect the country,” he said, “what you do is you put the country at greater risk.”

Bishop Madden worries that Trump’s plan and other recent sentiments expressed by U.S. and European political leaders will be put to use in places where hopelessness reigns among Muslim young people. That may not just be in the immiserated refugee camps he has visited in the occupied territories, Syria or Lebanon. Bishop Madden points out the the San Bernardino shooter was a well-educated U.S. citizen and that attackers in Paris were also European born and raised.

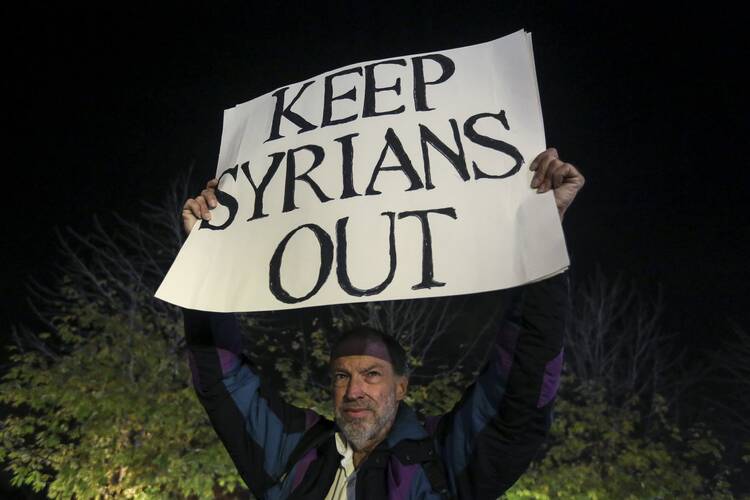

Collateral damage created by this recent bout of Islamophobia has been the public’s attitude toward Syrian refugees. After widely circulated images of drowned Syrian children provoked dismay all over the world, U.S. public sentiment shifted quickly toward a more generous asylum policy. After San Bernardino and Paris, that sentiment has shifted sharply away. Now these refugees, says Bishop Madden, have become ISIS-victims twice over—first in being driven from their homes and now in being denied refuge. That response “makes no sense,” he says. Procedures for resettlement in the United States are strict, according to Bishop Madden. The review process can take up to two years and in light of recent events will probably take longer. “There is a process that people go through; there’s a lot of vetting. People don’t just show up at the airport with a passport from Syria.”

Bishop Madden adds that the United States needs to do more to relieve the refugee crisis than the 10,000 it has agreed to accept next year. Other countries, like Germany, are accepting significantly higher numbers of refugees. The U.S. numbers represent a start, he thinks, that is “better than none” but hardly sufficient to make a dent in the humanitarian crisis.

Bishop Madden thinks U.S. Catholics should step forward in a special way to respond to anti-Muslim prejudice and its collateral political effects. “It’s part of our DNA,” Bishop Madden suggests, "and I think during this year of mercy that we should be especially sensitive to this.

“Pope Francis has so emphasized starting off with our realization of God’s love for us, God’s mercy towards us, and if we really could appreciate that I think we'd be a bit more generous in being merciful and being loving to others,” he says.

“We have a Sacrament of Reconciliation—it’s part of who we are as Catholics. We do this. We don’t hold grudges; we don’t lock people up to make sure that nothing happens and we’ll all be safe.” In terms of promoting healing and allaying fear, “I think we’re well-equipped for it,” the bishop says.