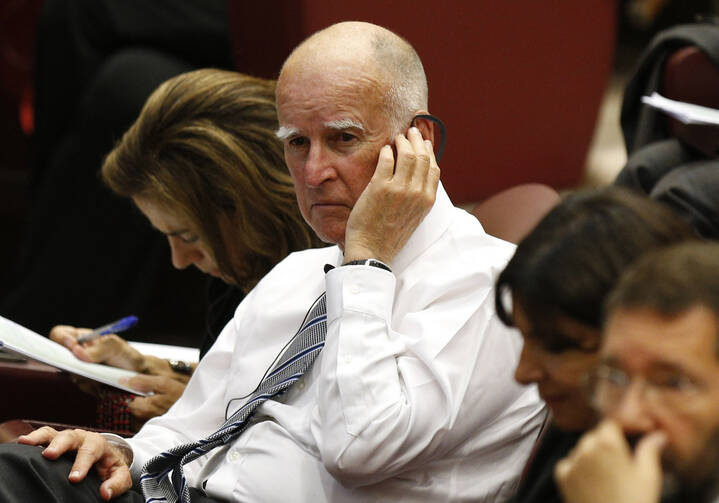

One of the more interesting aspects of California Governor Jerry Brown’s decision to sign assisted suicide legislation into law yesterday was the thoughtful reflection he offered in his announcement. “ABx2 15 is not an ordinary bill because it deals with life and death,” he wrote. “The crux of the matters is whether the State of California should continue to make it a crime for a dying person to end his life, no matter how great his pain or suffering.”

In his one page statement, he describes his own process in coming to a decision—talking to friends and doctors, a bishop and the pleas of different groups. “In the end,” he writes, “I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death.”

“I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

I suspect most people reading this will agree with Governor Brown; one might choose to face one’s own final days in any number of ways. But who is any of us to deny reasonable options to anyone else?

It’s the great problem, really, of the Catholic position against assisted suicide—on the face of it, it doesn’t seem grounded in the mercy and compassion one expects of the church, particularly at such a profoundly personal and difficult moment. One can argue until one is blue in the face that in fact pain management is not the problem that people fear it is, that in fact in Oregon, where assisted suicide has been legal for decades, most who choose that path do not do so because of pain. But still, there are cases, such as that of Britney Maynard, in which the pain cannot be managed. And the Catholic option of medicating the patient near or into a coma seems a meaningless, if not in some cases a cruel distinction.

But here is the danger of which we must stay aware: that assisted suicide becomes the cheap alternative to health care. That might sound ridiculous, great for a movie script but not ever the way things will work in reality. And, it must be acknowledged, the California legislators have worked to ensure that insurance companies will not be able to change what they cover as a result of this alternative.

But it’s also true that this legislation was brought forward over the summer during a special session in which Governor Brown had specifically been asking the legislators to help him brainstorm ways of dealing with rising health care costs. And alongside this bill, nothing of substance was done to address that financial issue.

As Edward Dolejsi, executive director of the California Catholic Conference pointed out in mid-September, “To its promoters, ABx2-15 is about compassion and choice. Where is the compassion when Medi-Cal won’t pay for pain relief but the Legislature responds by making physician assisted suicide ‘affordable?’

“And where is the choice when literally millions of Californians are told there is no coverage for second opinions or their cancer care, but look, we’ve made suicide an affordable option?”

California disability advocate Justin Harford echoes these concerns, noting that those Californians who live in poorer communities or rural communities, as he does, do not receive the same health care as elsewhere. “They’re not as likely to get sufficient pain management, they’re not as likely to get sufficient testing—we see this in the disability community, too.” The consequence is, as Dolejsi states, there is no real choice. “If you don’t have the right to choose to get chemotherapy when you get cancer, then it’s rather a phony choice to say you can ‘choose’ assisted suicide.”

Admittedly, these are possible outcomes, doomsday scenarios, as are the oft-expressed fears that giving doctors the ability to help end a life will make some people less likely to trust them, or that the terminally ill or disabled may end up feeling pressured to die, or that no matter what the legislature might think, insurance companies are almost certainly going to find ways to steer people out of treatment and into suicide. What will actually come of this new law, which today gives those with six months or less to live the right to have a physician prescribe them medicine, is still to be seen.

But we would be well advised to keep our legislators’ feet to the flame. In the California legislative debate politician after politician rose to speak in a heartfelt way about the demands of compassion. But to express concern about the way a person dies and at the same time not fund their ability to live or receive proper care is not compassion but inhumanity and expediency.