Some North Americans may deride migrants from Mexico as at best economic opportunists or, even—as one candidate for president has suggested—criminals, but Stephanie Brewer knows them more intimately as people escaping some of the most serious variants of human rights abuses imaginable.

A Seattle native, Brewer is the international coordinator for the Jesuit-sponsored Miguel Augustín Pro Juaréz Center for Human Rights in Mexico City. The center acts as direct advocates for victims of human rights abuses but also works to promote political progress on human rights across a gamut of social concerns. In Mexico the work is measured out by the decade as successive governments make rhetorical commitments to improving human rights that seldom translate into practical results. Brewer knows firsthand how economic and political structures in Mexico come down hardest on its most vulnerable, particularly subsistence farmers and indigenous people driven from their land by shifting agricultural policy or the unwelcome interventions of oil, agricultural or mining interests.

Founded in 1988, the center maintains a special focus on the people in Mexico who face the gravest human rights violations: women, indigenous, migrants and children.

“What we have here in Mexico,” says Brewer, “is the intersection of several of the most serious human rights violations.

“So the most common abuses that we are documenting and hearing about … are torture, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, arbitrary detentions.” These serious and persisting human rights abuses in Mexico, she adds, “are knit together” by a system of collusion between authorities and organized criminal groups. “That scenario is one of the most serious problems facing the country,” she says.

The age old question in Mexico: Is this a problem of the government’s lack of will or capacity? Both probably, she says. “Currently what we need is a very strong expression of will and very strong actions directly tackling corruption, directly tackling impunity, to break this cycle we’ve been stuck in for many years."

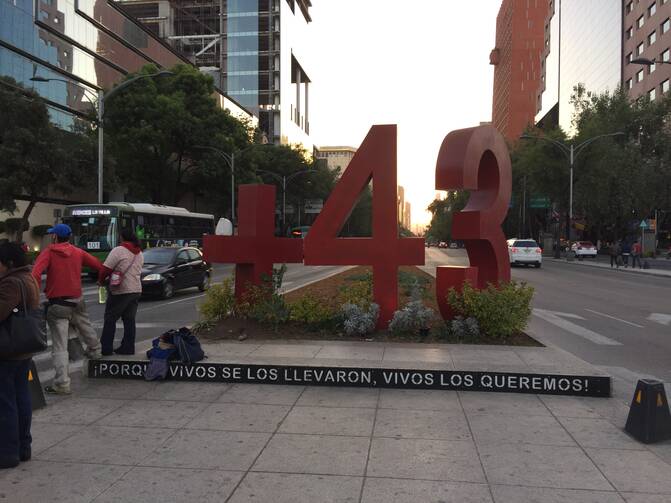

The level of violent crime and collusion with criminal forces by political leaders and security forces became embodied in September 2014 by the disappearance and apparent murder of 43 students in Guerrero state. Finding out what happened to the students has been a national obsession, propelled by the images of the parents of the disappeared who have been fearlessly, and so far fruitlessly, demanding an explanation of the disappearance of their children and official and criminal accountability for the same. The 43 Ayotzinapa students vanished in 2014 after they were kidnapped from a bus. According to the Mexican government, they were incinerated by members of the drug cartel Guerreros Unidos. Mexican security officials claim the ashes of the 43 students were found in Cocula, a city in the state of Guerrero, but these government explanations so far have been unconvincing to all parties, including forensic experts who have reviewed the government’s evidence and found it woefully lacking.

“We’re still waiting and the parents of the students are still waiting for real information and real advances from the government in that investigation,” says Brewer. The still unsolved disappearance and presumed mass homicide has galvanized public outrage into action, street protests and a continuing demand for change. Photos of the missing are hung along the walkways of the city's Paseo de la Reforma.

Though the disappearance of the such a large group simultaneously is rare in Mexico, part of the reason the case has drawn so much domestic and international attention, Brewer describes the missing 43 as a “representative case” of the kinds of human rights abuses that plague the nation.

“Unfortunately with about 27,000 people registered as potentially disappeared in the country and many other victims not even entering into that register,” she says, “we can’t say that the Aytozinapa case, the case of the 43, is an isolated case, rather it’s a particularly brutal face of this problem that continues to occur every day.”

President Enrique Peña Nieto returned the PRI, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, to power after a 12 year absence in 2012, on a promise of moving the nation away from the disastrous war on drugs that led to a blood bath during the administration of his predecessor Felipe Calderon. By the end of Calderon’s administration, the official death toll of the Mexican Drug War was at least 60,000; some estimates are much higher.

Mexicans who had hoped for a shift away from a militarized state under Peña Nieto have been disappointed. “We haven’t really seen that change; the country continues to be militarized,” says Brewer. “Police forces continue to lack proper supervision and controls and incur abuses.” And te impunity with which Mexican police, military and security forces operated during the war, and continue to operate, has meant that despite these many thousands of deaths and disappearances essentially no member of the government security forces has been called to accountability. That's often despite clear evidence of their collusion with drug cartels and other criminal enterprises.

Other issues of acute concern at the center included the treatment of women in Mexican society, abused by both their domestic partners and "sexually tortured" while in detention by government security forces, and Mexico indigenous peoples. With government’s primary interest focused on extraction of national resources from on or underneath land long claimed by indigenous communities, the rights of indigenous are frequently violatedand their claims sometimes violently suppressed. That propels more people into the migrant flows to a perceived refuge in the north.

In terms of the pope’s visit this week, Brewer is hopeful that the nation’s fundamental problems with human rights will remain at the top of the pope’s speaking agenda. “Certainly everyone, in terms of the victim’s movements and civil society organizations of course we do want him to speak on these issues…We think that it is vital for him to speak out on some of these serious human rights abuses.”

Human rights advocates may have those hopes realized. Holy See officials have invited the parents of the 43 missing students to join Pope Francis during Mass in Juárez on Feb 16. Beyond any rising expectations courtesy of Francis’ visit, Brewer says those looking for signs of hope for real progress on human rights should consider the example of the parents of the disappeared and victimized who are no longer able to be silent.

“In spite of their loss and pain and suffering—and uncertainty because they don’t know where their children are; they don’t know if they’re alive or dead—and in spite of threats, violence, you name it, they continue to fight,” says Brewer.

“When you see that strength and that refusal to give in, refusal to be intimidated,” she adds, “that’s something I think should call out to the international community and say, ‘We do have hope here; we do have potential here and this is where it is,’ but we do need for everyone to be aware of what is happening in Mexico and we do need support from all sides.”

Editor’s Note: America’s Olga Segura and Kevin Clarke will be following Pope Francis during his visit to Mexico this week, bringing you stories about the people and communities the pope will be encountering.