To grow up with the Gospel is a blessing, which none should eschew, yet the familiarity of youth can have the unfortunate effect of benumbing the bewilderment, by which the Gospel intends to be received. The scriptures are written for adults. By way of astonishment, they seek to reorder an adult world. However variegated, even vitriolic, our understanding of them can become in the course of sharing the scriptures with others, in themselves, they’re plain spoken, enough for any adult to make some sense of them. More to the point, the scriptures speak to adult concerns, as anyone, who has ever tried to teach, or preach, them to young children can attest.

Have you ever attempted to explain to a child what it meant for David to slay the Philistines, the nature of his rooftop attraction to Bathsheba, or his plot to eliminate her husband Uriah? In the New Testament there is the Slaughter of the Innocents, the Beheading of the Baptist. This is not even PG-13 material. Many people have never read the scriptures for themselves. They’re content to have them occasionally pronounced from the pulpit, never realizing how this prunes away some of the stickier parts.

The scriptures are clearly addressed to adults. They speak of suffering, desire, death, revenge, hope, and patience. Yes, young children have some experience of these, yet how grateful we are that it is circumscribed. We seek to shield children from the concerns of adults.

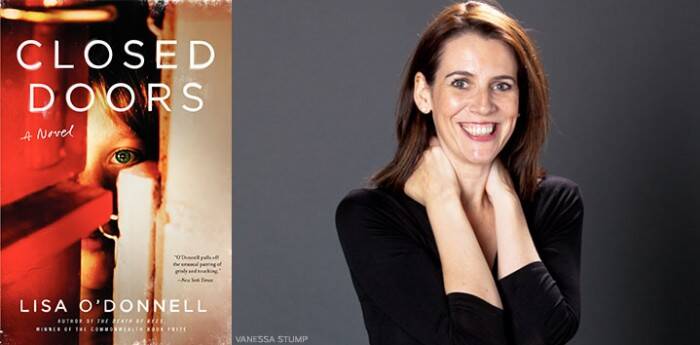

Lisa O’Donnell’s new novel records that awkward year in which Michael Murray, an eleven year-old Scottish boy, discovers the existence, if not the meaning, of sex. That should have happened in its own, bumptious manner at school. Instead, his mother is raped. The novel takes it name, Closed Doors, from the attempt of his family to shield Michael from an ugly world.

“You’d rather they thought you beat your wife to a pulp?”

“It’s what Rosemary wants,” he cries.

“And what do you want?” asks Granny.

“I want to kill the bastard,” cries Da, and then there’s a banging on the table.

“A lot of good that will do now. We don’t even know who he is,” says Granny.

I’ve heard enough and go back to my room. In the morning I am full of questions. Granny folds laundry and Da looks tired. I ask him about flashing. He doesn’t want to tell me. Neither does Granny. They want me to disappear with my soccer ball, but I don’t. My ma has been flashed at and I want to know what it means. She’s in the hospital with a sore face and a limp. She fell hard because of this flasher. I have a right to know what’s going on and why I’m to tell everyone she fell on the stairs. Da gives in and tells me flashing is when a man shows a woman his willy and makes her afraid for her life, and so I hope Dirty Alice is flashed. I hate her more than anyone in the world. She’s ruined my whole life because no one will talk to me or play keepy-uppies with me and now Paul MacDonald might fight me because I told on him for kissing Marianne. I don’t want to fight Paul MacDonald, he’s bigger than me. Paul MacDonald is bigger than everyone (18).

Given the difference between childhood and adulthood, a distance measured in dolors, it may initially seem that Jesus expects us to maintain the innocence of childhood, at least to do all that we can to keep it intact.

Taking a child, he placed it in the their midst,

and putting his arms around it, he said to them,

“Whoever receives one child such as this in my name, receives me;

and whoever receives me,

receives not me but the One who sent me” (Mk 9: 37).

But the Gospel isn’t a pious version of Peter Pan. It never asks us to do what cannot be done, only that which is difficult to do. Parents rightly shield their children from the cares, concerns, and crisis of the adult world, but they cannot stop them from entering that world. The Gospel runs deeper than delaying adulthood.

To receive the child is to make room for children within the Church, but it is also to seek the strengths of the child for the soul of the adult. Two of those are resiliency and trust. Together they create a pliancy, a suppleness of the soul. Children recover faster than adults. Their stream of hope is fresh and deep. Children—sadly, sometimes to their undoing—are born trustful. They expect adults to tell them the truth, to protect them, to cultivate a world in which they can thrive.

Children aren’t perfect. Indeed they can be quite cruel, but when Jesus asks us to receive the child, he wants us, under the impulse of grace, to redeem, to find again, the suppleness of youth, the resiliency and trust that allow us to confront the world as those who know they are beloved of the Father. Of all the truths the Gospel reveals, none is so hard to believe, so difficult really to trust, than that we are beloved of God and therefore can run the risk of living deeply.

[T]he wisdom from above is first of all pure,

then peaceable, gentle, compliant,

full of mercy and good fruits,

without inconstancy or insincerity (Jas 3:17).

By the close of the novel, Michael and his family are recovering. The boy has grown a great deal, but at the cost of suppleness. The forfeiture of childhood trust and resilience are the admission price of adulthood. Michael is growing up, but he must still grow back into suppleness.

Drinking champagne and having a good old time. Ma finds my eyes watching her across the room. She makes a kissing motion and sends it to me in the air. I am supposed to catch it like a baby and today I think I will. It might have made me cry if I was a baby, but I not a baby. I am the toughest lad in the estate and the toughest lad in the estate doesn’t cry about anything in the whole wide world. Not one thing and not today (246).

Jesus went to the cross, a terribly adult reality, with the trust and the resiliency of a child. His soul was supple, because he had lived his life as the beloved Son of his Father. It was his deepest identity. Jesus truly believed, in the words of Wisdom, that

if the just one be the son of God, God will defend him

and deliver him from the hand of his foes (2:18).

We sometimes say that the child is the father of the man. In Gospel light, to be an adult is to reclaim the best of the child: resiliency and trust. So, in the words of the song, “may you stay forever young.”

Wisdom 2: 12, 17-20 James 3: 16-4:3 Mark 9: 30-37