Donald Trump knows how to hijack a news cycle, and part of his appeal among Republican primary voters is that he generously brings his supporters onto his plane. If you’ve ever wanted to be interviewed by CNN or USA Today, what’s a better plan than to attend a Trump rally?

This week Mr. Trump commanded attention by proposing to ban all Muslims from entering the United States, uncharacteristically doing so through a presumably copy-edited press release rather than spontaneous remarks. The New Yorker’s Amy Davidson reported from South Carolina, where Mr. Trump read his own statement at a campaign stop:

‘Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.’” (“The hell” wasn’t in the official statement.) “We have no choice,” Trump said, as the crowd interrupted him with loud applause. “We have no choice.” He shook his head as the cheers continued and he said, a third time, “We have no choice.”

Josh Marshall reacted to the plan by comparing the Trump campaign to an infamous psychological experiment in which subjects were easily persuaded to administer ever-more-painful electrical shocks to strangers. “Let’s not pretend,” Mr. Marshall writes, “that this latest provocation will somehow sink Trump's popularity or burst the enthusiasm of his supporters. All the evidence—past experience with Trump and polls on issues surrounding Muslim Americans among GOP voters—suggests this will drive his numbers higher.” (I’m waiting for someone to compare Mr. Trump to someone slowly heating up water and the American public to a frog that doesn’t realize it’s being boiled to death, if only to see James Fallows demolish this myth once again.)

In The New York Times, economist Justin Wolfers suggests that Mr. Trump will indeed benefit from what even most Republican leaders are calling his blatantly unconstitutional and un-American proposal, but not necessarily because voters agree with him. Mr. Wolfers argues that the Trump campaign is all about branding. “How can you convince voters that you are in fact the real deal—a trustworthy person who speaks his mind—rather than yet another poll-driven politico?” writes Mr. Wolfers. “The answer is that you do something that a poll-driven politico would never do, such as making a statement that will alienate many voters…. It’s devised to make you infer that he’s not like other politicians.”

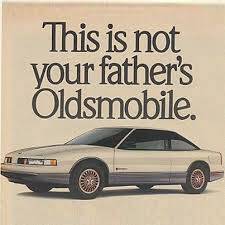

In economics, this is called “signaling.” Imagine Mr. Trump saying he’s “not your father’s presidential candidate,” to borrow an iconic advertising slogan. (He could use it literally against Jeb Bush.) According to Mr. Wolfers,

Mr. Trump’s outrageous statements signal that he has [a] political virtue some voters value,” or that mysterious substance known as authenticity. “Some of his supporters may be willing to vote for what his policies signal about his personal character, even as they find these policies repugnant.

It’s hopeful, and perhaps naïve, to assume that many of Mr. Trump’s supporters find his policies repugnant. Still, no one has actually voted for him yet, and we’re still weeks away from finding out if his big poll numbers will hold up when the GOP primary season gets underway. There have been plenty of candidates who have attracted crowds with straight talk and telling it like it is, but they usually lose altitude by election day. (Granted, Harry Truman won by “giving ’em hell,” but Mr. Truman would surely be appalled by Mr. Trump’s demagoguery.) Mr. Wolfer’s only example of someone getting into office by campaigning against “politics as usual” is Jesse Ventura, elected governor of Minnesota as an independent way back in 1998.

The “signaling” theory makes some sense. I think a great many Americans use it to vote for candidates who make unrealistic promises about tax cuts (or who pledge to never raise taxes), reasoning that someone who makes such emphatic statements can be trusted to resist taxes for as long as possible. In 1984, Democratic nominee Walter Mondale tried his own form of authenticity, telling viewers in his acceptance speech, “Mr. Reagan will raise taxes, and so will I. He won’t tell you. I just did.” This was a disastrous form of signaling, as many Americans interpreted Mr. Mondale’s statement not as honesty, but as an admission of priorities (tax increases over spending cuts). The best possible interpretation of Mr. Trump’s support is that he “signals” an aggressive approach to terrorism even if his specifics are often counterproductive and seemingly more appropriate to North Korea than the United States.

Still, it’s tough to accept this charitable explanation when you hear from some of Mr. Trump’s supporters and see the kind of prejudice on display at a presentation for an Islamic center is Fredericksburg, Va. “Every Muslim is a terrorist, period,” says one attendee at the zoning meeting. “Shut your mouth.” The video from that meeting is at Vox’s discouraging round-up of “out of control” Islamophobia in the United States, which seems to have ramped up since Mr. Trump entered the presidential race.

“Maybe the fever will break after the 2016 election cycle finally ends,” writes Vox’s Max Fisher, “12 very long months from now.” That may be too late if voters support “signals” of hatred toward Muslims all the way through next November.