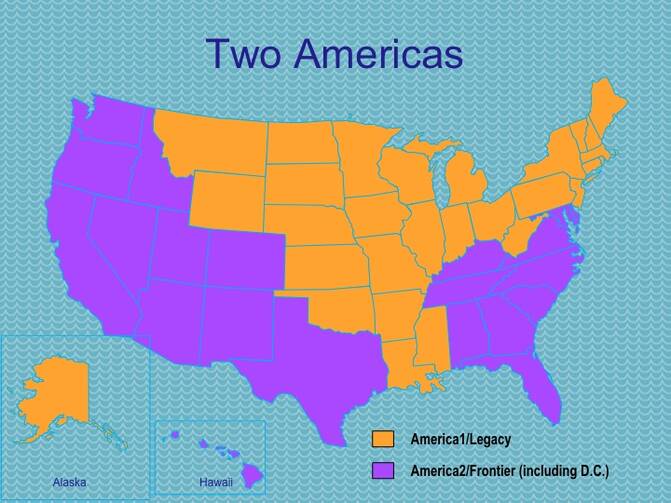

Data maven Adam Carstens looked at the latest state population estimates and came up with a new way to divide the United States. “America1” (which he calls “Legacy” in a subsequent post) is old and slow-growing, depending on immigrants to avoid population loss. “America2” (or “Frontier”) is mostly in the Sun Belt and has robust population growth from not only immigrants, but also native-born Americans fleeing cold temperatures and high housing costs. (For my earlier take on the new population data, see “Immigration and Population Growth Are Also Dividing America.”)

President Obama carried both of the regions in 2012, but was a bit stronger in America1, which covers 29 states (“the Northeast, the Midwest, the Mississippi Valley, the Northern Plains and Alaska”). Mitt Romney barely lost the 21-state America2 (“the coastal Southeast from the Mason Dixon line south, as well as Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama, as well as Texas, much of the West and Hawaii”).

Carstens writes, “Barring a major reversal of trend, America1 will continue to be heavily reliant on international immigration to maintain its population. Thankfully, many of the best educational institutions in the world reside in America1, as well as major financial, industrial and energy centers.”

But Frontier will outpace its older brother in population growth (and, by extension, political clout): “America2’s major advantages are that it has plenty of land available in nice climates, as well as the willingness to build new housing to meet that demand. Outside certain parts of California, there isn’t really a ‘preservationist’ ethic inside America2—there is a willingness to do what it takes to build. Most of America2 is so ‘new’ that a preservationist ethic has not yet taken hold. Granted, it may develop one someday, but not yet.”

Carstens seems to be intentionally avoiding a rehash of red vs. blue maps, and it’s refreshing to get away from the idea that political polarization is breaking the country cleanly in two. But…

America2 would definitely lean Republican if not for California, which doesn’t really belong there. As Carstens admits, its “preservation” pockets are no longer hospitable to new housing. The state is no longer a Shangri-la for the rest of America, and more U.S. citizens are now moving out than in. (It’s gaining population through births and immigrants, which puts it in the same category as Massachusetts.) The other West Coast states of Oregon and Washington are still benefiting from domestic migration, but I suspect that preservationism will eventually slow down housing construction in those liberal states as well.

I would instead divide the country in three (see map below), combining the West Coast with the Northeast Coast from New Hampshire to Virginia for a region that is staying afloat, population-wise, thanks to immigrants and the limited number of high-income professionals that can afford to move there. It could be called Gateway since it’s always been a major destination for immigrants, in good economic times and bad. Besides, Carstens describes America1 as focused on “energy production, agriculture and manufacturing,” which doesn’t fit the megalopolis from Boston to Washington.

That leaves America1 with most of the states that are losing native-born people but aren’t attracting enough immigrants to power economic growth. It would include eight of the 10 slowest-growing (or shrinking) states in the latest estimates: Alaska, Illinois, Maine, Michigan, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and West Virginia. (The others are Connecticut, which has a high number of immigrants but a low birth rate, and New Mexico.)

As I mentioned in my earlier post, such slow-growth states, which don’t fit either the post-industrial economy of the coasts or the housing-boom economy of the Sun Belt, are losing political clout. At the same time, voters in those states are especially likely to seek solutions from the 2016 presidential candidates on such problems as wage stagnation and long-term unemployment.

Carstens’ map puts Arkansas in the slow-growth region of America1/Legacy, and former Gov. Mike Huckabee coincidentally signaled this week that he’s considering another presidential run. In some ways, Huckabee is the natural representative of Legacy within the Republican Party: a cultural traditionalist who’s among the last furious opponents of same-sex marriage and a vague economic populist who’s hostile toward Wall Street even as he shares the GOP’s stand against big government. He’s also a natural foil to former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, a proud citizen of America2/Frontier and a believer in its “everyone can be a winner!” ethos.

Unfortunately for Huckabee, he’d be an underdog in that fight. He could win the Iowa caucuses in Legacy (as he did in 2008), but Bush would have little trouble defeating him in Gateway’s New Hampshire, and Bush would be a heavy favorite in the big Frontier states of Florida and Texas. The problem for any Legacy candidate is that he or she carries the stink of stagnation, and voters in the rest of the country don’t want to be associated with “left behind” states. Even within the Legacy region, voters in big cities like Chicago don’t like we’re-losing-our-way candidates. That’s why Mitt Romney was able to defeat Rick Santorum in the 2012 Republican primaries in Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, despite losing most of the counties in each state. America1 won’t come out on top in 2016.